We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

Router and hand tools combine for line and berry inlay on this 18th-century piece.

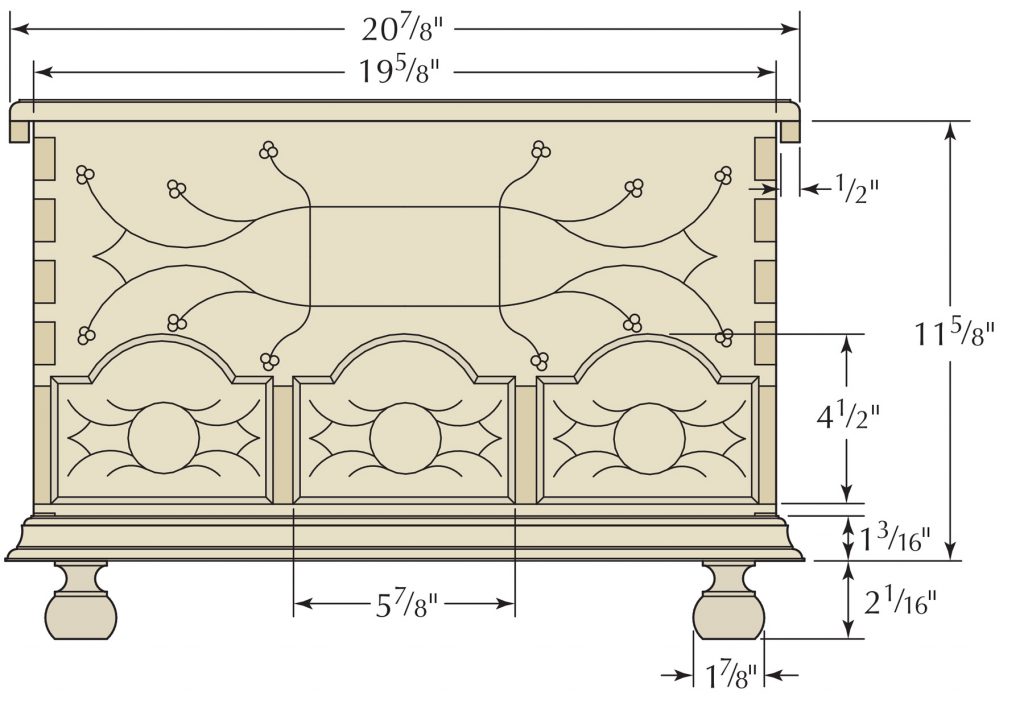

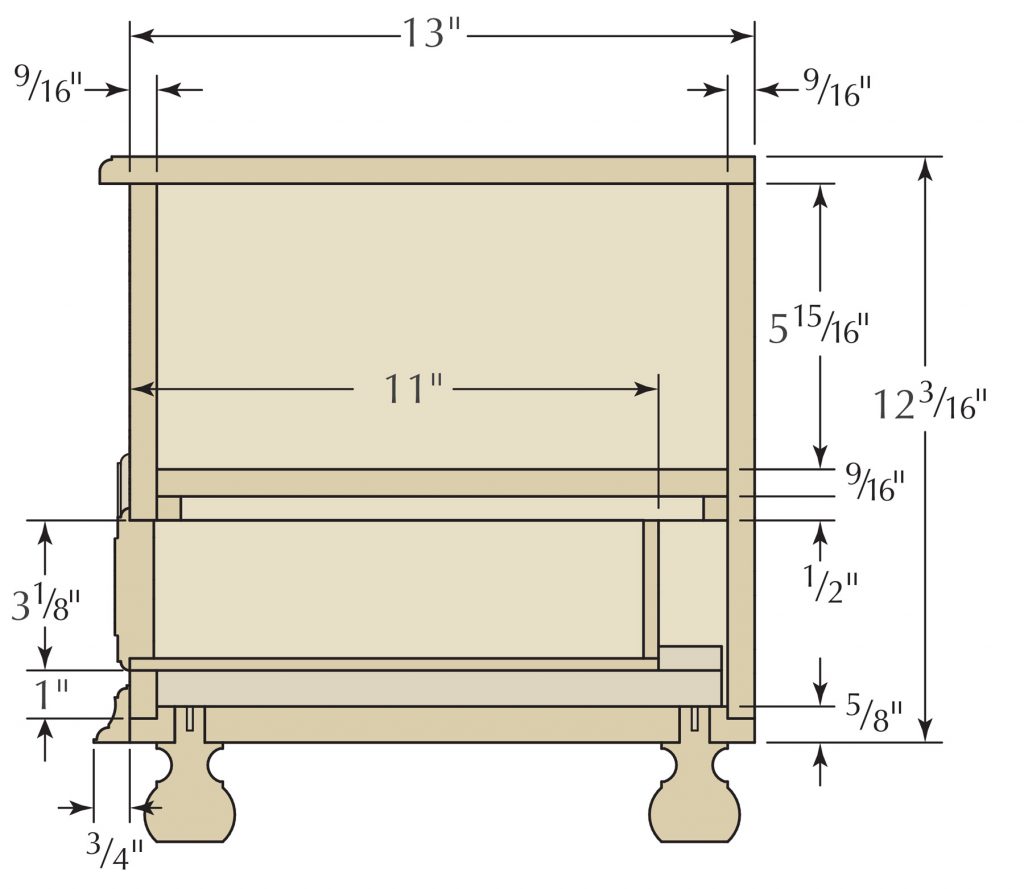

In 1746, at the age of four, Hannah Pyle stored her prized possessions in a small three-drawer chest with line and berry inlay. Lines of holly stringing on the front of that chest included her date of birth and initials – a common practice in southeastern Pennsylvania in the mid-1700s. The pale white numbers and letters stood out against the dark walnut background, as did the inlay on each of the three arched-top drawers.

Hannah’s father, an accomplished Pennsylvania cabinetmaker named Moses Pyle, built the chest for his daughter. A second chest, also with inlaid initials and drawer fronts, was owned by Hannah Darlington, Pyle’s sister-in-law. Her chest, built a year later in 1747, is also attributed to Pyle. That chest is now part of the collection at the Winterthur museum. I left the date off my chest and chose to work with mahogany.

Scratch a Design

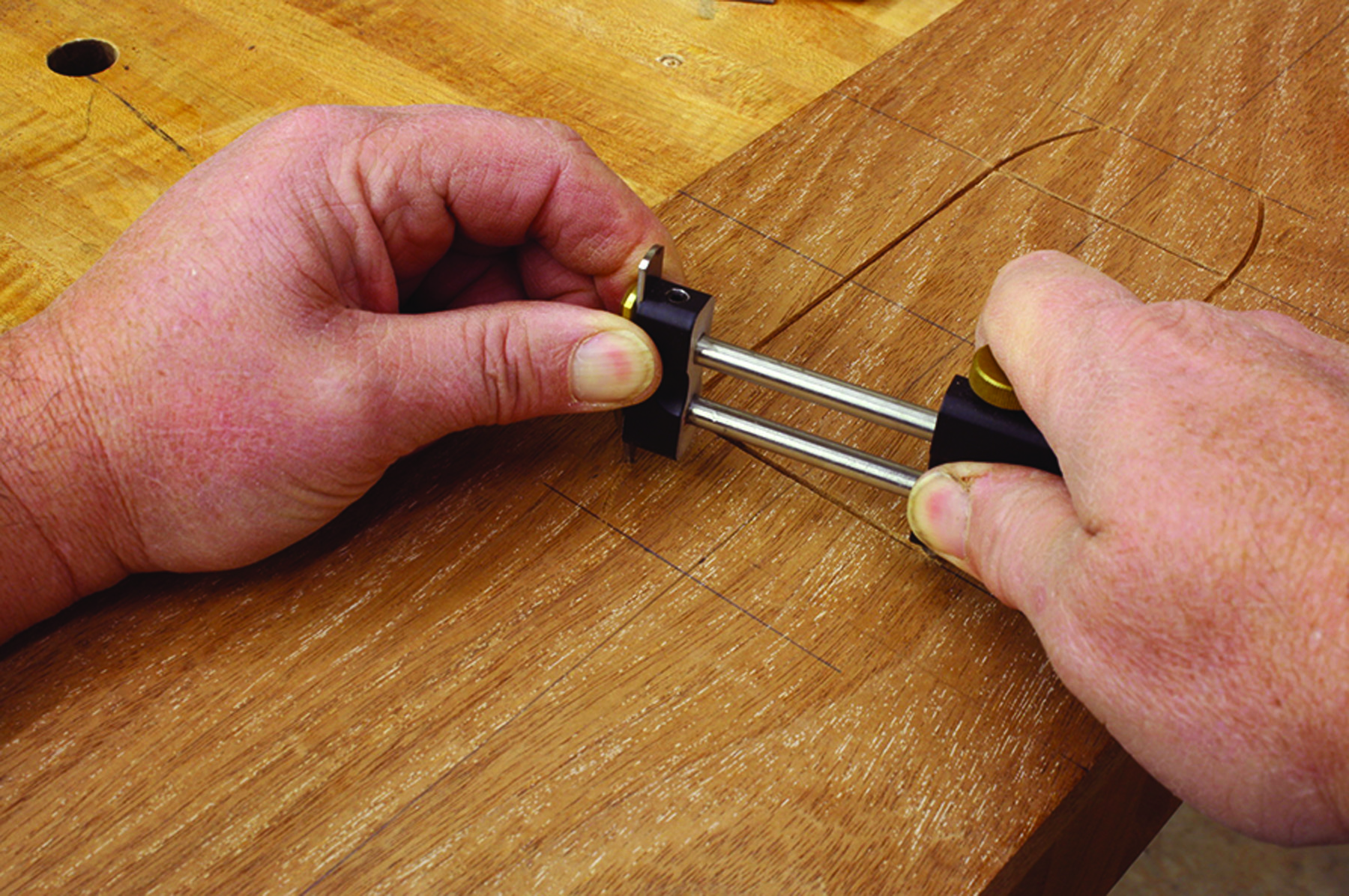

Begin radius work. Use a back-and-forth action as you scratch the pattern and be mindful to keep the pivot point planted.

There are two natural starting points for this project. If you’re new to dovetails, build your box then do the inlay work – it would be disheartening to complete the inlay work only to trash the piece as you dovetail. If, on the other hand, you are dovetail-savvy, begin with the inlay.

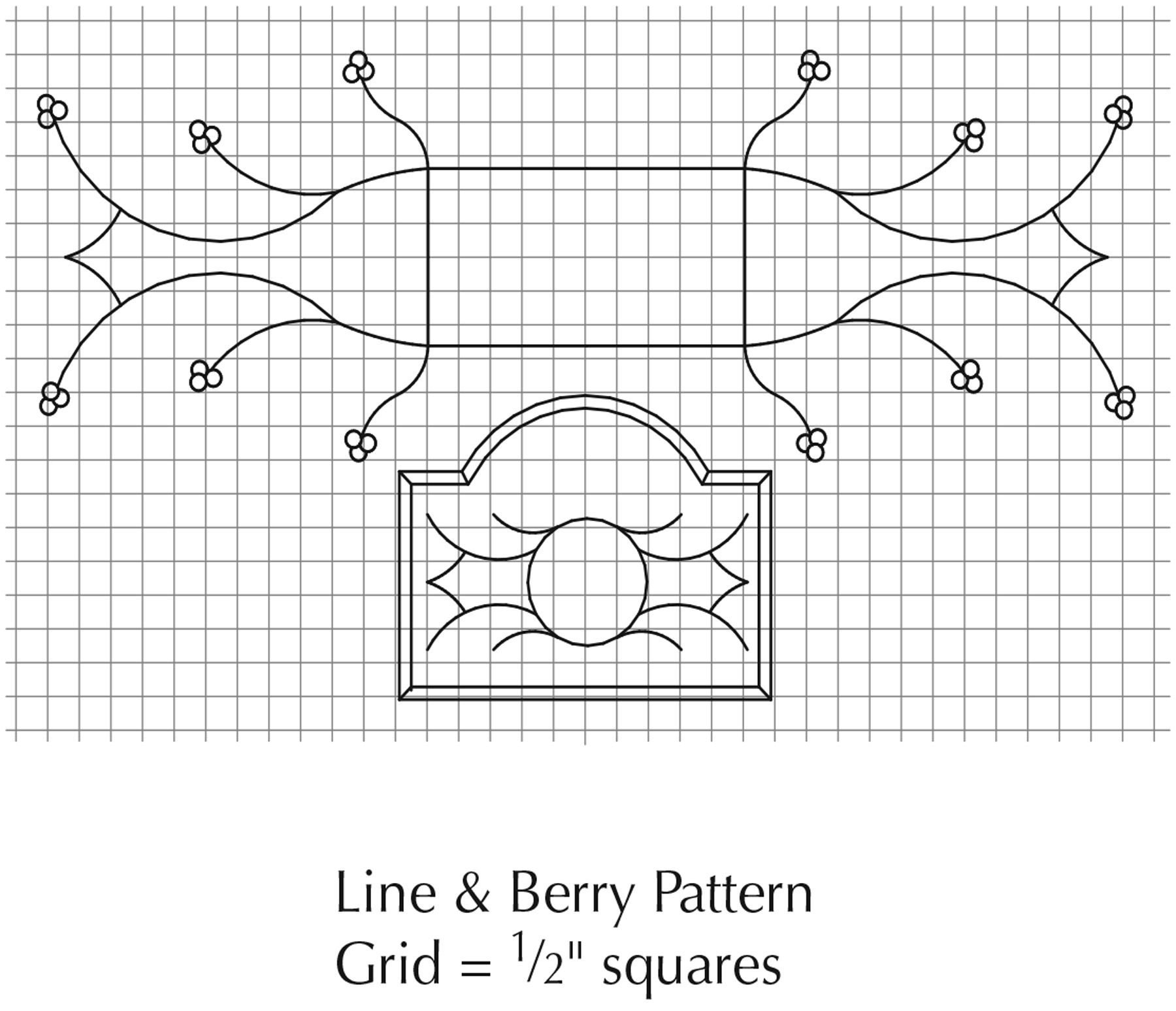

Grooves for stringing can be created using a router setup, scratched by hand or with some combination of the two. For the straight lines of the box front, I suggest a trim router and a 1⁄16“-diameter bit. For all other grooves, a radius cutter and .062″ blade (available from Lie-Nielsen Toolworks) works great.

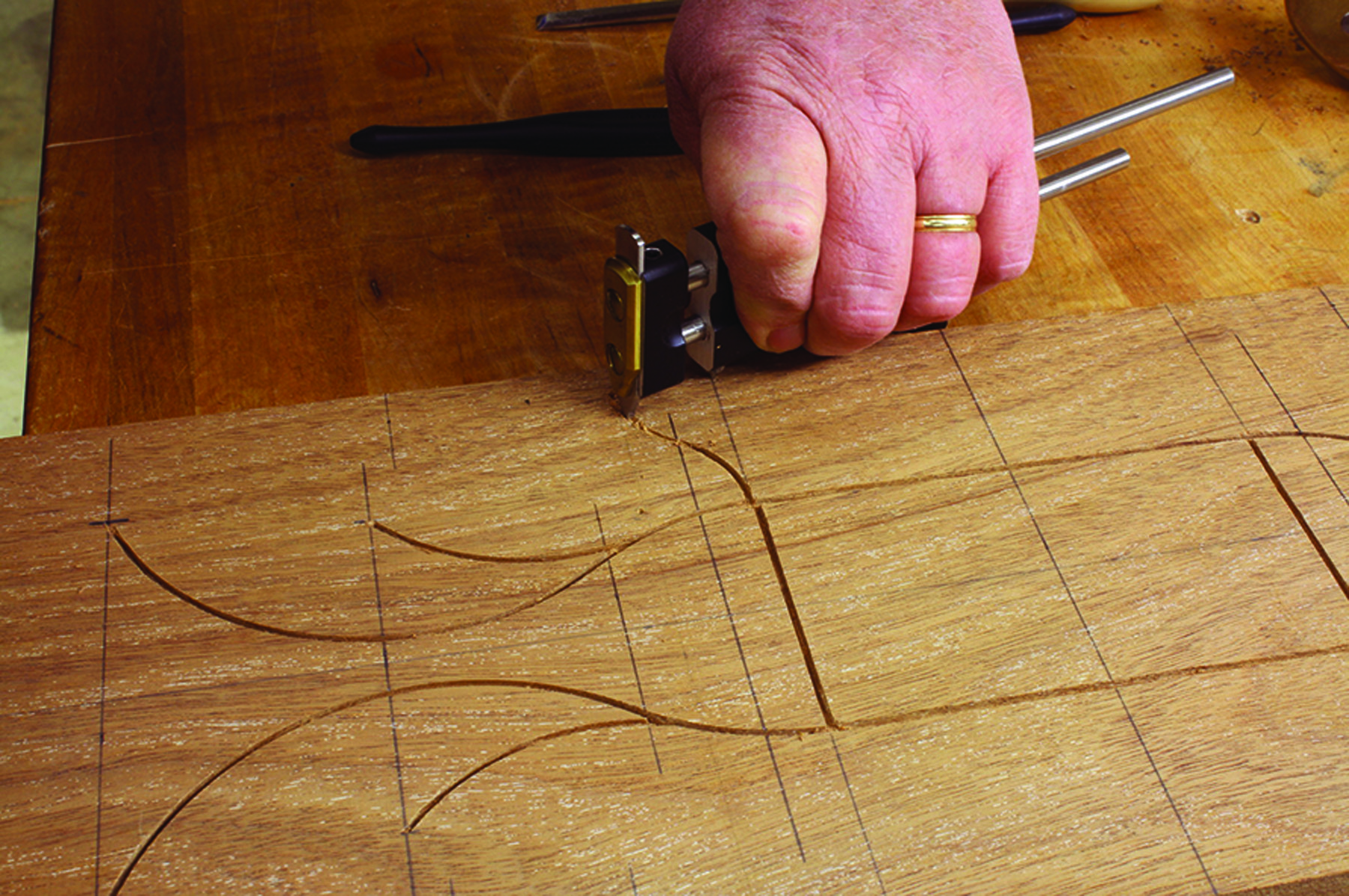

The key. A successful inlay design is accomplished only with a smooth transition from arc to arc.

To begin, cut your box front to length and width then mark its center. Work off the centerlines to layout the sides of the 2 5⁄8” x 5″ rectangle at the center of the design. Use a router with a guide fence to cut the top and bottom lines then use a router and a shop-made dado jig to complete the shape. (Details of my jig are available online.)

The remaining lines – all arcs scratched into the chest front– rely on layout accuracy. Measure and draw lines at each step to keep your four quadrants identical.

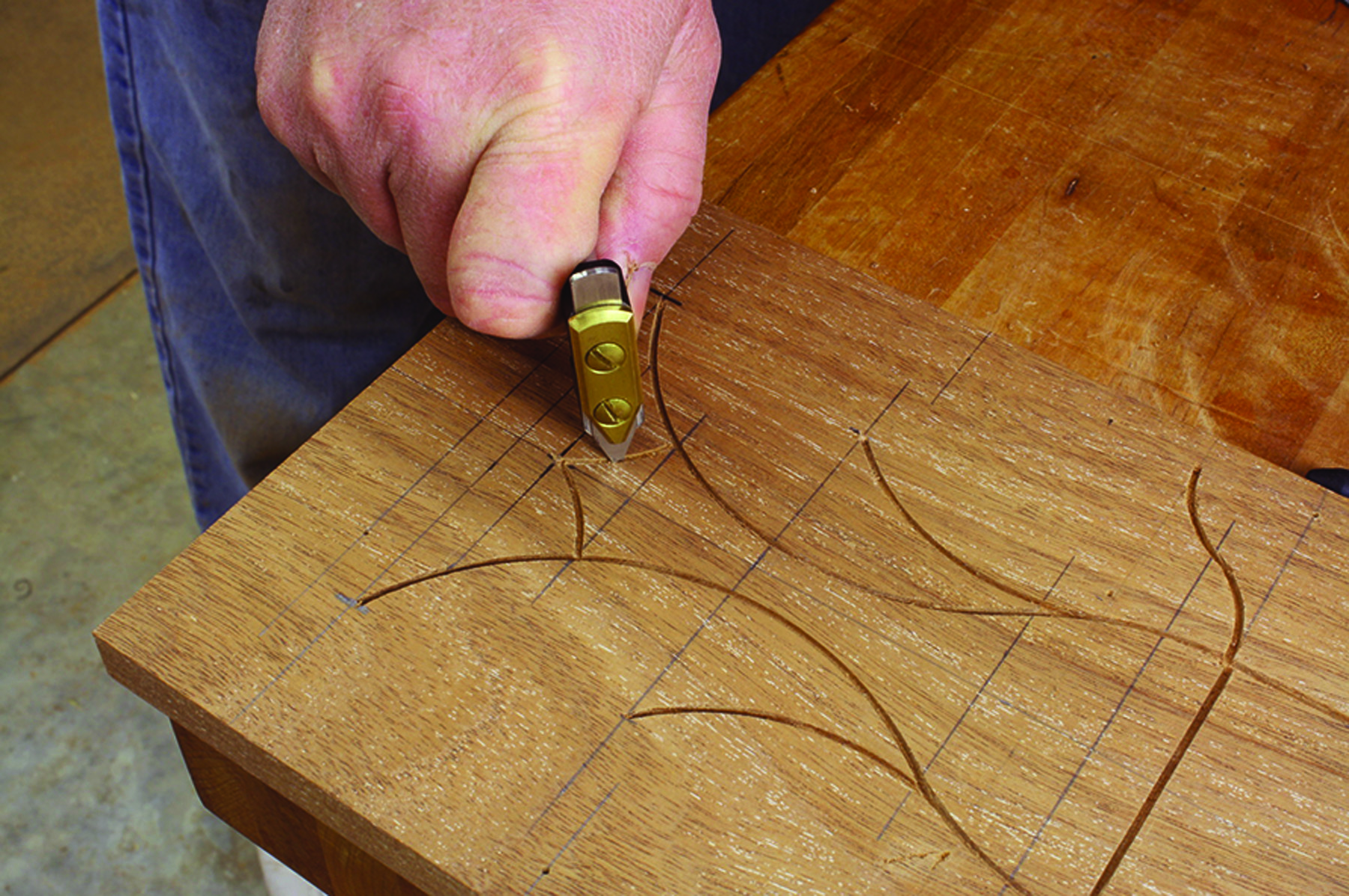

Two arcs, one radius. The short S-shaped line is a double arc made with the cutter set at a 1″ radius.

Draw a line 17⁄16” beyond the ends of the rectangle. Set your radius cutter at 2 5⁄8” (equal to the rectangle’s side length), position the pivot point of the radius cutter at a corner then swing your groove out to the line. Repeat the steps at all four corners.

To create the second groove – the longest – slide out another 4 1⁄2” and draw a vertical line across the front. Mark a line 1 7⁄8” from the horizontal centerline. Set the radius cutter to cut at 2 3⁄4“, then find a pivot point that allows the tool to reach both the end of the first groove and the point marked on the outermost line.

Get the point? The design pattern repeats over the four quadrants of the front. The only connection of the arcs is the arrow near the ends.

The third groove begins at the intersection of the first two arcs then moves out 2 1⁄8“. The tool is set at a 2 1⁄8” radius, which indicates that the pivot point is aligned with the intersection.

The S-shaped line begins at the corner of the rectangle and arcs out toward the end 1⁄2“. The second section of groove transitions from the end of the first and continues out another 1⁄2” as seen in the photo above left.

The last grooves in the design form an arrow that connects the quadrants. From the outermost vertical line, move back toward the center 3⁄8” then draw a vertical line. Draw a second line in another 3⁄4” then, with your tool set at a 1 3⁄4” radius, work between the two points.

Case Construction

Case Construction

An easier choice. Because the base moulding completely covers the lower-front rail dovetails, you could use an easier joinery method for the case in that location, such as a nailed or pegged butt joint.

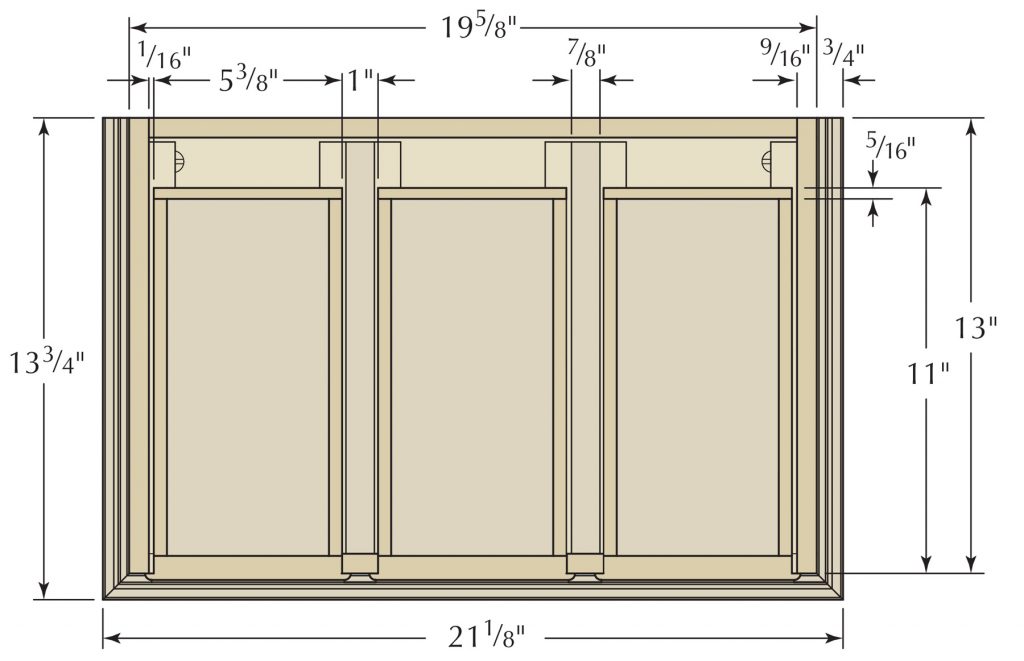

The four corners of this chest are dovetailed together. As with most chests of this design, the pins are in the front and back panels with tails in the ends or side panels. The size and number of pins and tails is left to your discretion. There are a couple tricky spots to bear in mind as you layout your joinery.

When working on the front panel, it’s best to begin the layout with a small half-tail at the bottom edge – this keeps you from making one 90° cut in your tail board when cutting your dovetails.

A second tricky area is the lower front rail. The rail has a single tail socket with half-pins on each side. Aesthetically, I would prefer this piece also begin with small half-tails, but its narrow width makes this impractical.

Smaller than usual. With the front’s thickness at 9⁄16″, a standard 1⁄4″ mortise would leave mortise walls too weak. Cut a 3⁄16″-thick mortise here instead.

Before any case assembly, cut the mortises for the two vertical dividers into the bottom edge of the front panel and the top edge of the lower front rail.

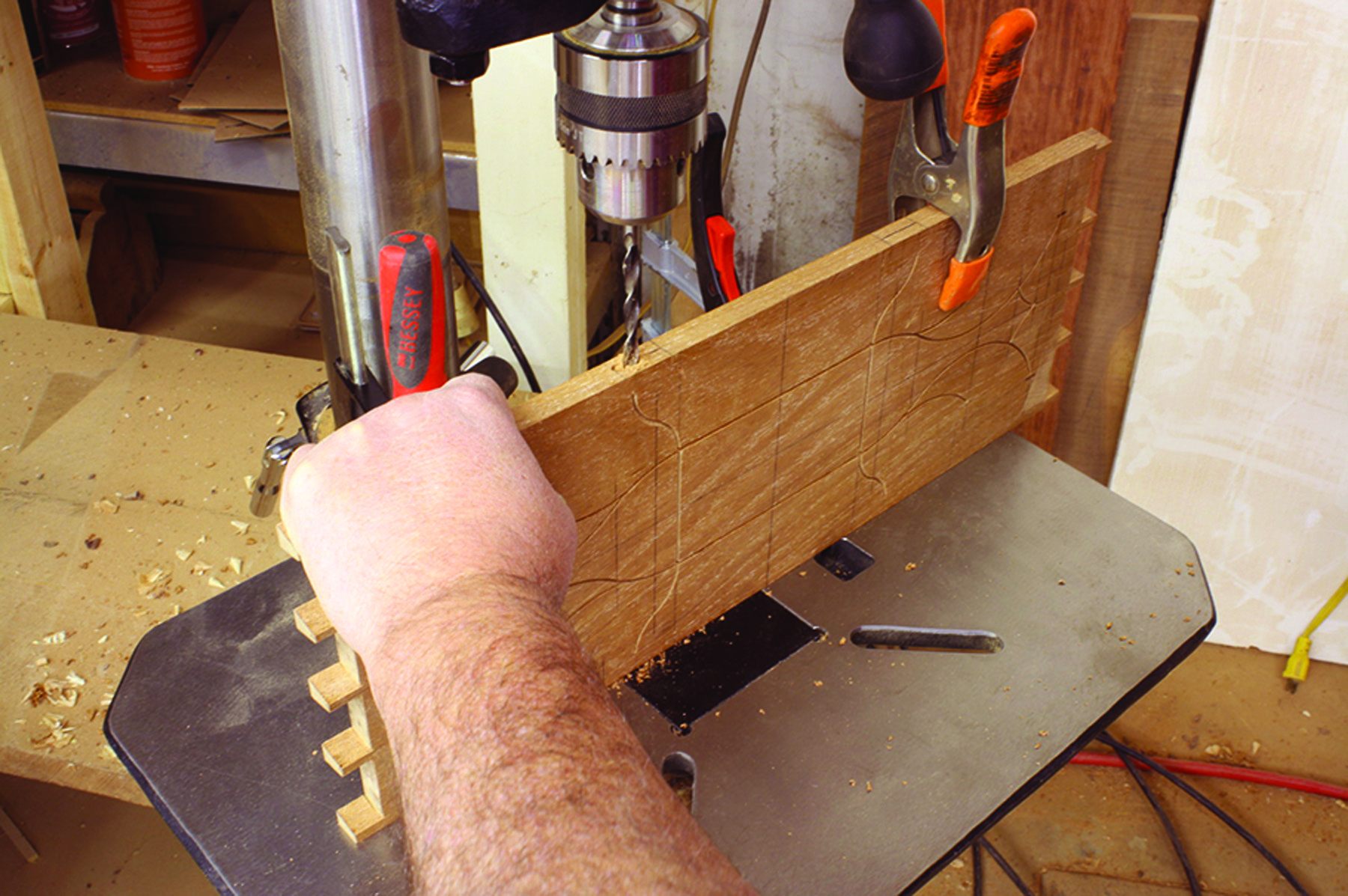

Because the rail thickness is 9⁄16“, keep your mortise at 3⁄16” in width for stronger mortise walls. I went with an “old school” power and hand approach to make the mortises; use a drill press to remove most of the waste then chisels to complete the 1⁄2“-deep mortise.

Two dividers are cut to width and length, including the 1⁄2“-long tenons. Rough-cut the tenons at a table saw, but leave them oversized. Use a shoulder plane to trim them to a snug fit.

Holly-lujah

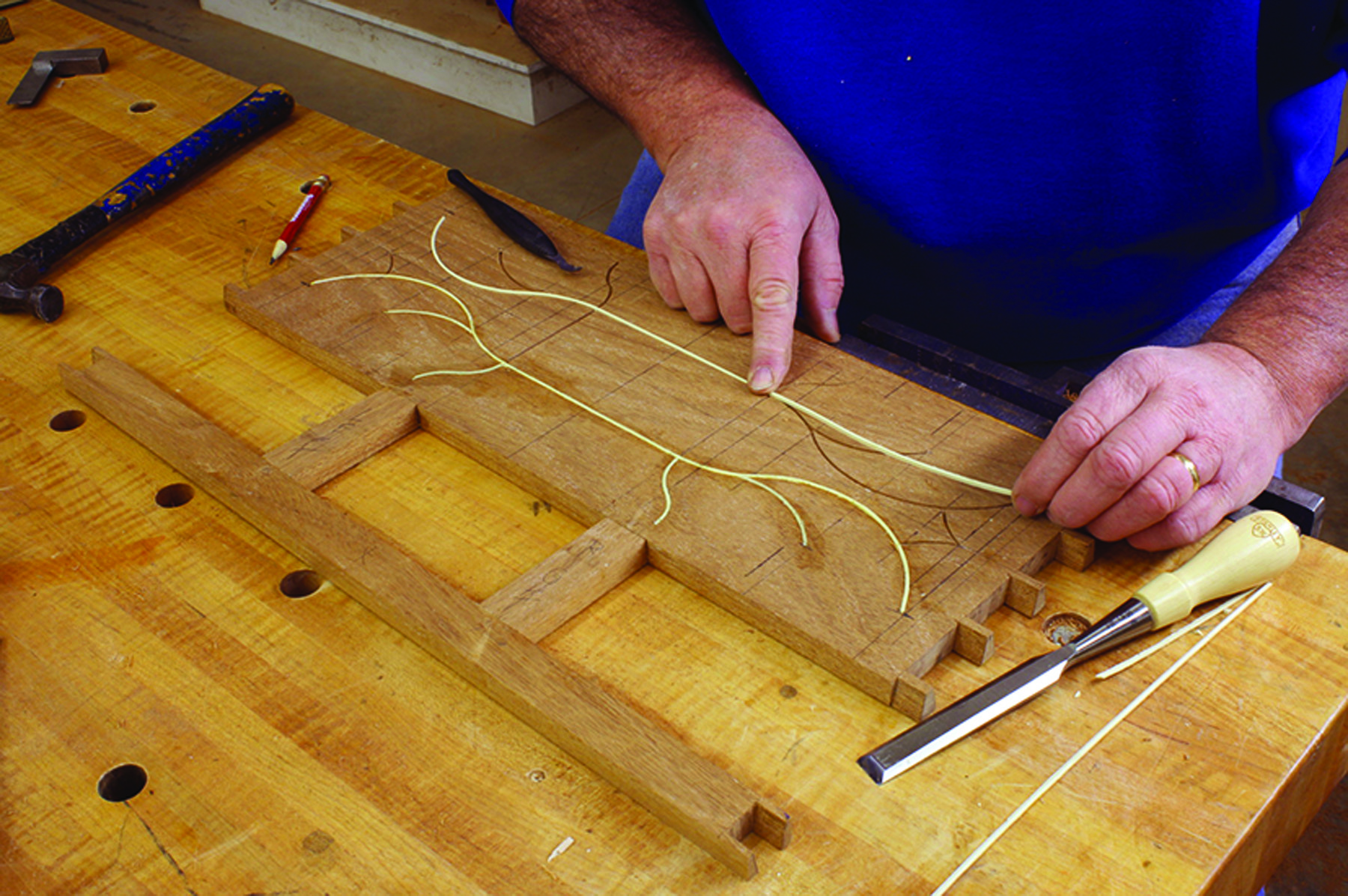

Long is better. When stringing a design, begin with the longest piece of inlay; you can then work to the shortest.

Before you assemble the case, cut and fit stringing into the grooves. An easy way to thickness stringing is to rip a couple pieces at a table saw with the fence set at a strong 1⁄16“, then sand the pieces between a shop-made fence and a spindle sander drum. Dial in a perfect fit by adjusting the fence’s position.

For string material, I use what’s in my shop, which is generally maple. For this piece, however, I chose holly. I found it easier to use. Grooves in this chest do not have a tight radius, but if maple is your string material, you may need to heat-bend a few pieces. Holly, at least in my experience with this project, does not require any heat-assisted bends; moist holly easily bends to fit these grooves.

Cut your pieces to length, but don’t worry about hitting the groove ends exactly. Berry placement covers a multitude of sins.

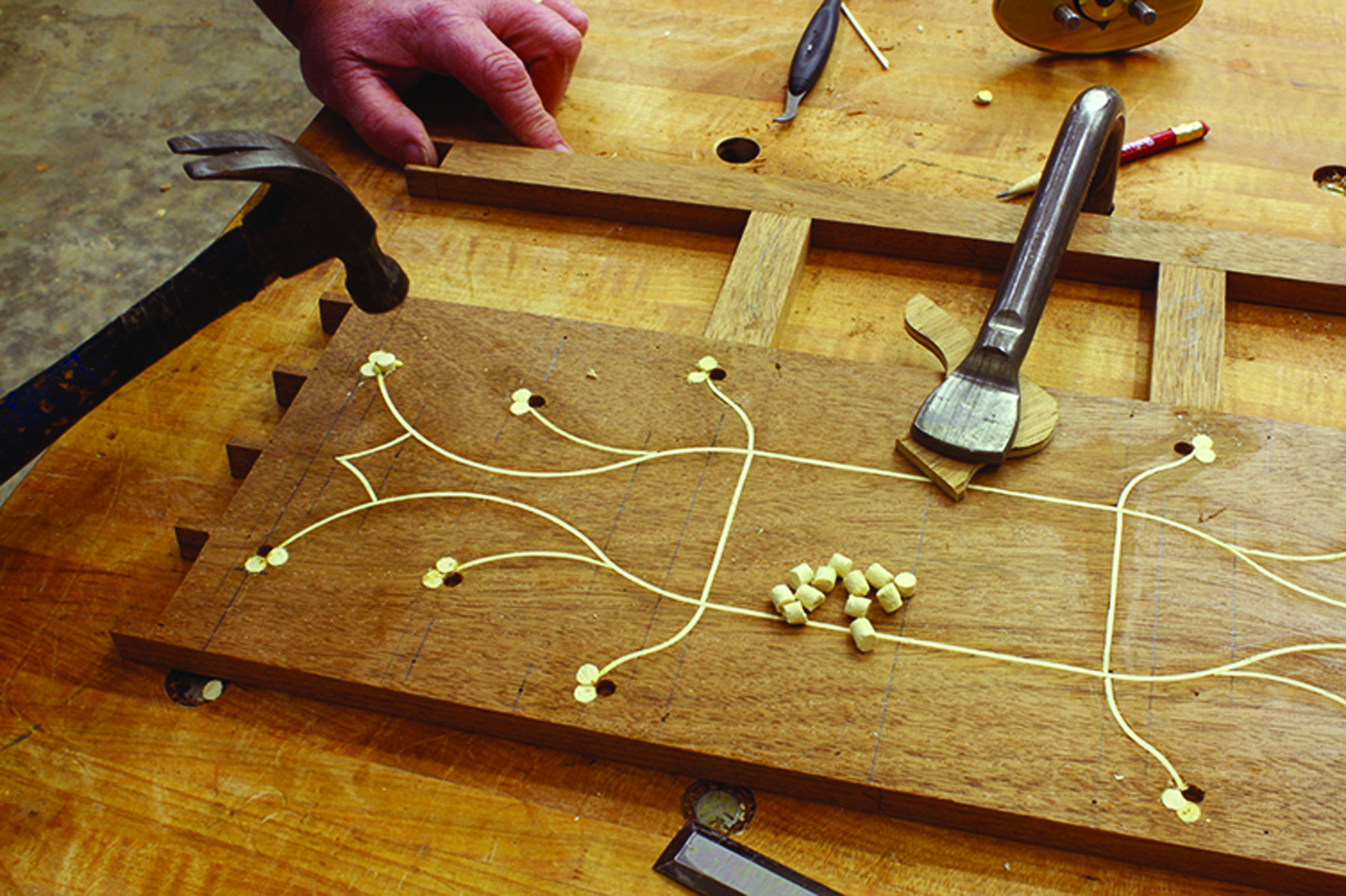

Grown by the bunch. As you install your berries, it’s better to arrange the plugs to replicate how berries grow in the wild. Nature forms bunches, not straight lines.

Berries are made using a 1⁄4” plug cutter at a drill press, and need to be 1⁄8” thick. There are 36 berries on the front panel, but always cut a few extra plugs. My piece of holly had a bad end that provided an otherwise unusable area from which to make berries. Cut your plugs, then use a screwdriver to pop them free.

To plant your berries, drill 1⁄4“-diameter holes about 3⁄32” deep at the ends of your string. For a realistic look, I find it best to drill and install the berries one at a time so they can overlap. After the glue dries on the first one, add a second berry to start to form a bunch. When the second installation is dry, drill and install the third and last berry. This process is time-consuming, but results in the best appearance.

After the glue for the berries is dry, apply glue to the pins and tails then assemble the case. Add clamps if necessary and make sure the case is square.

Hannah’s Inlaid Chest Cut List

No.ItemDimensions (inches)MaterialComments

t w l

Chest

❏ 1 Front panel 9⁄16 7 19 5⁄8 Mahogany

❏ 1 Front rail 9⁄16 1 19 5⁄8 Mahogany

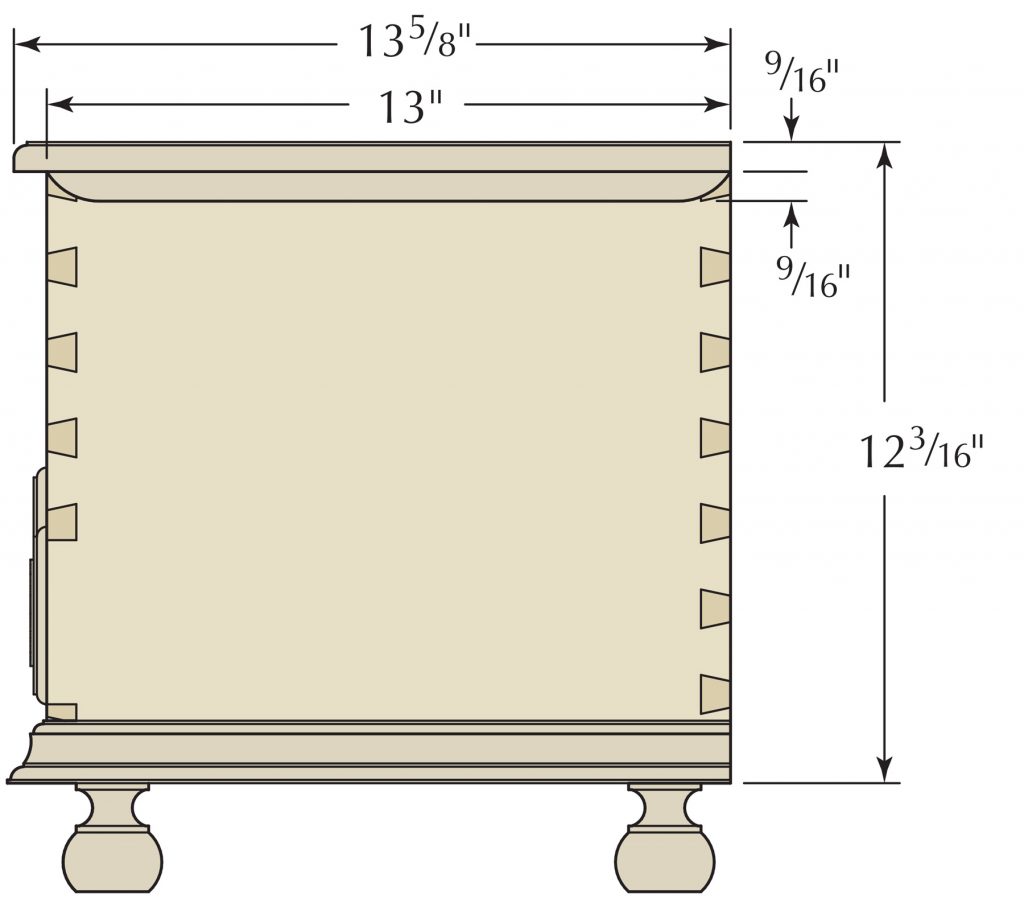

❏ 1 Side 9⁄16 11 1⁄8 13 Mahogany

❏ 1 Back 9⁄16 11 1⁄8 19 5⁄8 Mahogany

❏ 1 Lid 9⁄16 13 5⁄8 20 7⁄8 Mahogany

❏ 2 Lid cleats 9⁄16 9⁄16 13 Mahogany

❏ 2 Vertical dividers 9⁄16 1 4 1⁄8 Mahogany 1⁄2” TBE*

❏ 2 Cleats – long 1⁄2 1⁄2 17 1⁄2 Poplar

❏ 2 Cleats – short 1⁄2 1⁄2 11 7⁄8 Poplar

❏ 1 Chest – bottom 5⁄8 13 19 5⁄8 Poplar

❏ 1 Foot blank 1 7⁄8 1 7⁄8 16 Mahogany Material for 4 feet

❏ 2 Base moulding 3⁄4 1 1⁄4 28 Mahogany

❏ 1 False bottom 9⁄16 18 1⁄2 11 7⁄8 Poplar

Drawers

❏ 3 Fronts 3⁄4 4 1⁄2 5 7⁄8 Mahogany

❏ 2 Runners – outside 3⁄4 3⁄4 11 3⁄4 Poplar

❏ 2 Runners – middle 3⁄4 1 3⁄4 11 3⁄4 Poplar

❏ 2 Guides 5⁄8 7⁄8 11 3⁄4 Poplar

*TBE = Tenon both ends

Front

A Firm Foundation

Simple lathe work. Lay out the major transitions for the feet, including the top and bottom of the ball and the top edge just below the tenon that fits into the chest bottom. Use a parting tool to set the proper diameters then shape the ball and cut the cove.

Before you fit the interior parts, you’ll need to turn the bun feet. As turning goes, this is a simple task. Turn a design to your liking, or download the full-size drawing for my foot (see Online Extras). It’s best to make an extra foot if you’re not a talented turner so you can select the four feet that most closely match – but don’t sweat it if they are not identical. It’s impossible to see all four feet at the same time.

The chest bottom is milled to match the case and has a 1⁄8” x 9⁄16” rabbet cut along the outer edge. This allows the bottom to fit an 1⁄8” up into the case making 3⁄4“-thick material ideal for drawer runners. The thinner edge also minimizes the overall height of the base moulding.

The feet, after turning, are installed into holes drilled in the case bottom. Adjust the foot’s grain to run perpendicular to the bottom’s grain. Make a saw kerf across the foot tenon, add glue to a small wedge then tap it into the cuts to secure the feet.

A strong hold. Foot tenons slip into holes drilled into the bottom after each tenon is sawn with the grain to accept glued wedges.

As the glued wedges dry, mill and install the 1⁄2“-square chest cleats that support the false bottom. The chest cleats are flush and level with the front panel’s bottom edge. Glue and brads hold them in place.

With the case inverted, add a bead of glue along the front edge and halfway back the sides. Position the bottom assembly to the case then nail along all four sides.

Primarily for looks. Because these nails will be seen throughout time, the bottom is the perfect place to use period-correct reproduction nails. But don’t forget to drill pilot holes.

Mill the drawer runners and guides to size. The two outside runners fit tight to the sides and butt to the front rail. Middle runners split the vertical dividers and are squared to the front rail. Add a thin bead of glue to the front half of the runners, position them to the case then secure with brads. Drawer guides fit on top of the middle runners and are attached with glue and brads.

The false bottom above the drawers floats as it rests on the cleats. Mill the panel so the grain runs front to back in the chest to increase rigidity.

Mouldings & Top

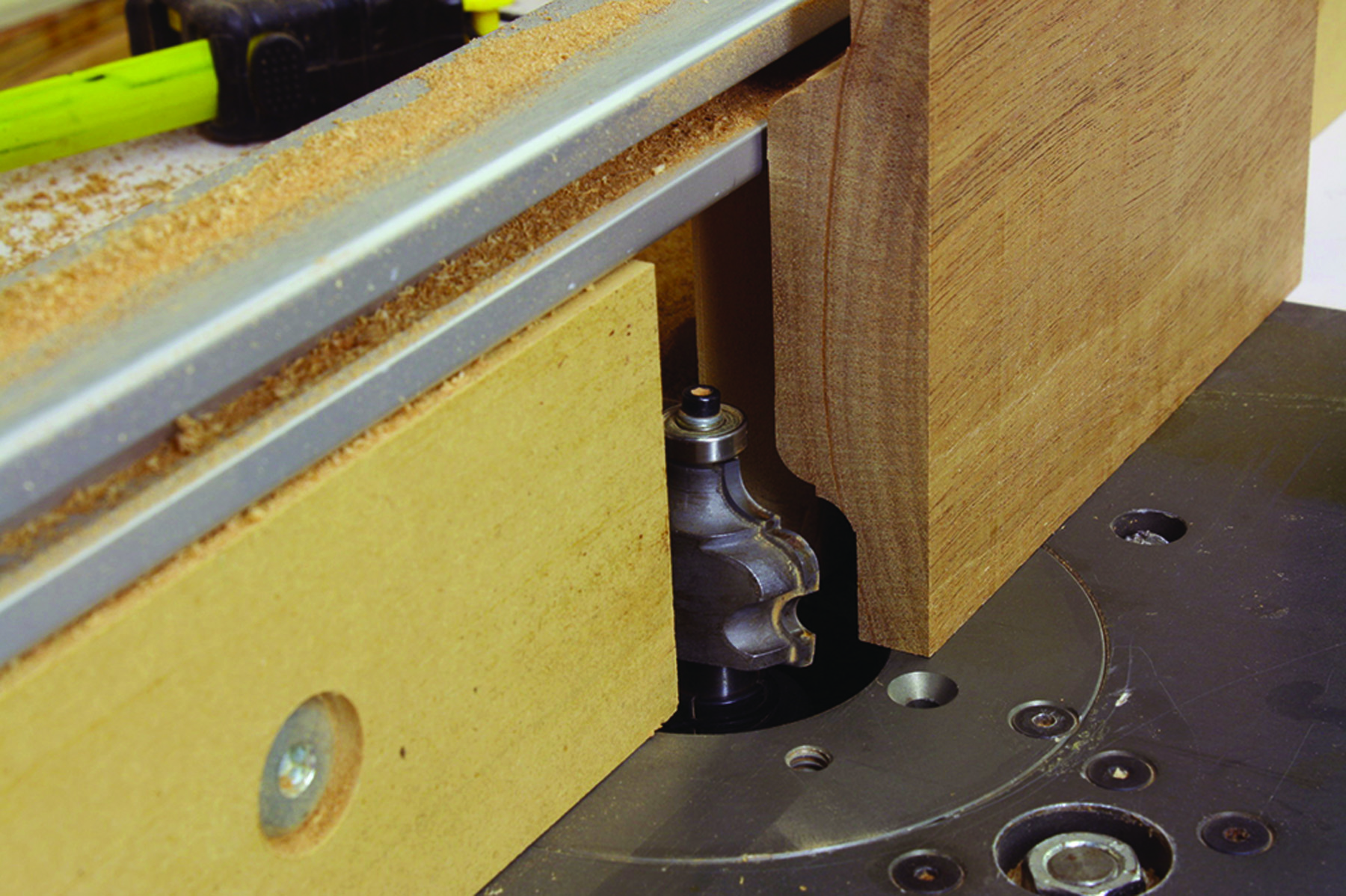

Incremental increases. I used a French Provincial Classical bit to begin my moulding profile. As planned, small increases in the bit height trimmed away the full-bead leaving only the cove-and-bead portion used.

The moulding on the case is a bit of a troublemaker in that it is 11⁄4” tall, but only 3⁄4” thick. This dictates that you stretch the profile more than most router bits allow, so be creative. Also, because the router bit cut is so high, it’s important that you make your moulding on a wide board.

Begin with a cove-and-bead router bit set up in your router table. Set your fence flush with your router bearing. To get the extended flat portion of the moulding as shown in the photo at right above, make a number of passes, raising the bit height with each pass.

Complete the two-step moulding profile by adding the roundover detail at the top edge. Use a 1⁄4“-roundover bit, and leave a small fillet for an additional shadow line. After completing this profile, trim your moulding from the edge of the wider stock.

Lying flat. With your workpiece flat to your router table, extend a 1⁄4″-roundover bit to the cut area. Set your fence flush with the router bit bearing.

Fit the moulding around the front and ends of your chest, then miter the corners. Apply glue to the entire front piece, but only along the front half of the side pieces. Brads finish the work and hold the moulding in place as the glue sets.

Mill the lid and lid cleats according to the cutlist. Profile the front and ends of the lid using a 1⁄2“-roundover router bit set to leave a small fillet. Cleats at the ends help hold the lid flat. Glue the front half of each cleat then screw them to the lid. Place the screws toward the inside edge of the cleats to keep them from poking through the top’s moulded edge.

Arched-top Drawers

Bring to a point. Rounded corners need to be squared. Continue the reveal to a sharp corner, then use a sharp chisel to trim both shoulders to transition the thumbnail.

The chest drawers are built with through dovetails at the back and half-blind dovetails at the front. The 1⁄4“-thick bottoms fit into rabbets cut in the drawer fronts and are nailed to the drawer box. Most of the work, including the string inlay, focuses on the fronts.

The arch of the three drawers is a centered 2 1⁄8” radius with the compass point set at that distance from the top edge. Draw the arch then mark a line 3 3⁄8” up from the bottom edge to locate the shoulders. After the shape is cut, form the thumbnail edges with a roundover bit. The inside corner at both ends of the arch needs to be squared as shown in the photo above.

Plane is better. Material behind the arch is nibbled away at the table saw, but final clean-up is best done using a shoulder plane.

Each drawer front is rabbeted as if it were a rectangle. The ends and bottom have a 1⁄4“-wide x 1⁄2“-deep rabbet. The entire arch, including a 1⁄4” at the shoulders, is also rabbeted. Make the cut at your table saw, then nibble away the area behind the arch.

The stringing pattern on the drawer fronts is offset toward the top of the drawer front. Position your pattern 15⁄8” from the thumbnail edge. Also, take the time to lay out the pattern to ensure you have adequate space for the pivot point of the radius tool.

Begin with the 7⁄8“-radius center circle. Remaining arcs transition from the circle and extend to the layout lines. This exercise is like that used on the case front. The one difference is that there are no berries used on the drawer fronts to mask the string ends.

Fit & Finish

Pattern tweak. String patterns are pushed above the center of the drawer front. Make sure you have ample room for the radius tool’s pivot point. It is tight.

The finish on my chest begins with a coat of boiled linseed oil to highlight the grain. After a coat of shellac, apply a layer of Van Dyke brown glaze to darken the project without discoloring the inlay. Follow that with multiple coats of shellac until a sufficient build is reached. Buff with #0000 steel wool to reduce the shine of the shellac.

Square ends. The grooves on the drawer front need to stop at your layout lines and the cut has to be at full depth to the very end. A nice trick is to use a screwdriver, sized to fit your lines, to crush fibers at the end of the lines.

With the finish complete, install an escutcheon with the area behind the keyhole drilled out and painted black – unless you choose to install a lock. The drop-pendant pulls are mounted using a snipe, and the lid is attached with small butt hinges.

I think this is a perfect project. Material costs are low and construction techniques are not over the top. As an introduction to string inlay, this design is easy and the work can be by hand or power. Just have fun with it.

Video: Watch an excerpt from the author’s “Line & Berry” inlay DVD.

Plan: Download a full-size drawing of the chest’s foot plan: Hannah’s Chest Foot

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.

Case Construction

Case Construction