We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

Portable, sturdy and easy to build, these were used for a variety of tasks.

Many of the fantastic furniture forms of the Middle Ages have disappeared and have been replaced by pieces that are more complex but not necessarily better.

One of my favorites is the early trestle table. It’s three pieces – a top and two sawhorse-like things – that can be instantly broken down, moved or stored. The form shows up in early paintings as being used for everything in the household: making pasta, butchering, surgery, writing, woodworking and fine dining.

Last year I built two of these tables for our home and have been delighted with how they look and function. One table is a roomy desk. The other table is used to accommodate extra dinner guests, serve wine on the front lawn and wrap gifts.

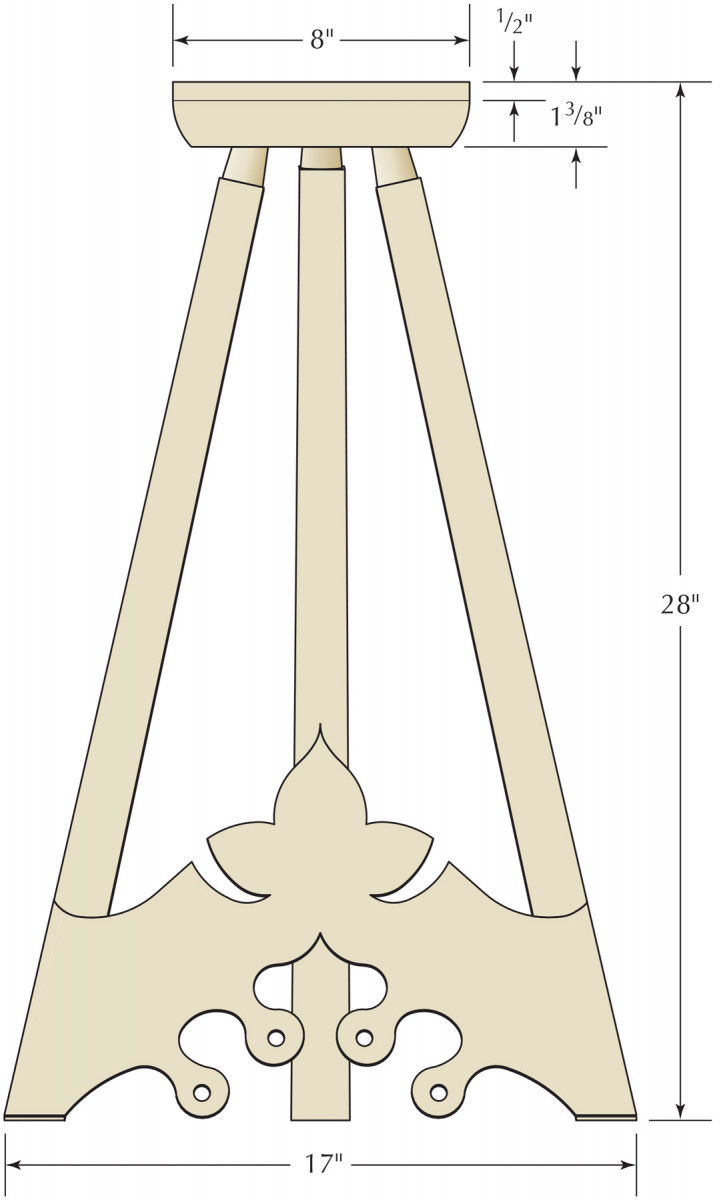

Not only are the tables versatile, they are simple and quick to build. The trestles are built using “staked” furniture technology, essentially a conical mortise-and-tenon joint that is more forgiving than its square-shouldered cousin. Each 8″-wide trestle top receives three legs for stability.

The two front legs are connected by a decorative stretcher, which features Arabic and Mughal motifs. If this stretcher doesn’t appeal to you, substitute a simple turned rung or a stretcher that is pierced with Gothic shapes.

The tabletop is a simple flat panel made from three pine 2x12s. The tabletop doesn’t have to be pretty because it typically was covered by a linen tablecloth.

Do not let the compound geometry of this project intimidate you. While it looks complex, even a beginner can manage it. Construction begins with the legs.

Tapers on Tapers on Legs

Second base. If the Mughal base doesn’t inspire you, try making the base with a simple turned stretcher, called a “spandrel,” that fits between octagonal or square legs.

The legs taper on all four faces so they are 15⁄8” square at the floor and 11⁄4“square at the top. This is easily done with a jack plane followed by a jointer plane. Mark out the finished dimension on the tops of the legs and jack plane the tapers. Clean up those tool marks with a jointer plane.

All downhill. If you use straight (or rived) stock for your legs, planing the tapers should be easy. Plane from the bottom of each leg to the top until the tops of the legs are 11⁄4″ square.

Next is cutting the tapered conical tenon on top of the six legs. The tenon is made using an inexpensive 5⁄8” tapered tenon cutter from Lee Valley Tools that works exactly like a pencil sharpener.

Ready for the tenon cutter. This tenon is 31⁄2″ long, 11⁄8″ at its base and tapers to a little more than 5⁄8″ at the tip.

To prepare each leg for the tenon cutter, you need to rough in a taper on the top 31⁄2” of each leg to make it easier for the tenon cutter. You can rough in the tenon by whittling it, turning it or using a drawknife.

Instant, perfect tenon. The tapered tenon cutter makes a finicky operation easy. Hold the tenon cutter firmly with one hand and the leg with the other. This particular grip allows you to eyeball the gap around the tenon to ensure it is centered on the leg.

The goal is to create a 11⁄8” diameter at the base of the tenon that tapers to about 5⁄8” at the tip. I used a lathe, which is fast. After roughing in the tenon, shave it to final size with the tapered tenon cutter.

Legs complete. After a trip to the tenon cutter, this is what the legs look like. The chewed up bits at the tips will be sawn away later.

Trestle Tops & Geometry

Mortise layout. You are looking at the mortise locations for the two front legs. Note the baseline that connects the two mortises and the sightlines that are 14.6° off the baseline.

The trestle tops are the interface between the legs and the tabletop. While you can leave them as square-edged boards, old paintings typically show them with slightly curved edges (and even what appear to be halves of logs). I used a jack plane to round over the long edges and ends of the trestle tops, so the underside was 7″ wide x 241⁄2” long.

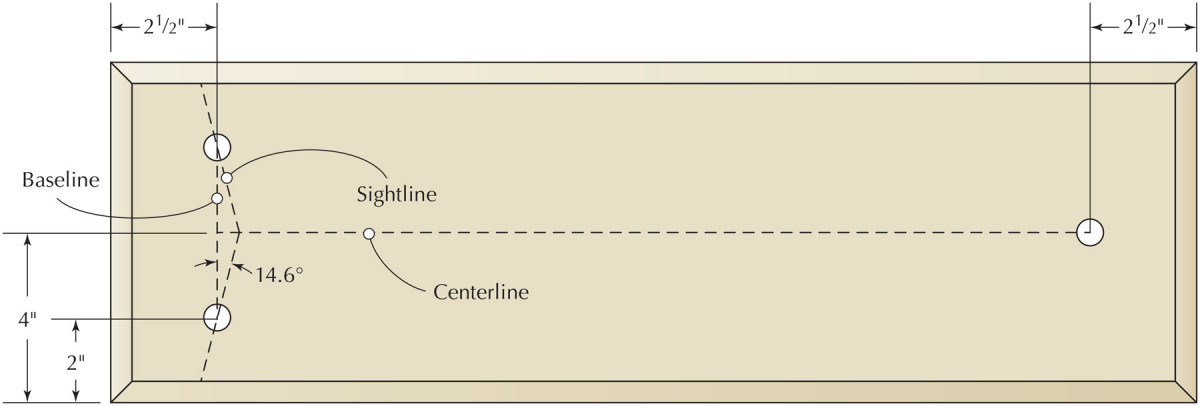

To lay out the locations of the mortises, first strike a centerline on the underside of the trestle top. The mortises for the two front legs are 21⁄2” from the ends of the trestle top and 2″ in from the edges. The mortise for the single third leg is centered on the underside and is 21⁄2” from the end. (See the drawing at the top of the next page.)

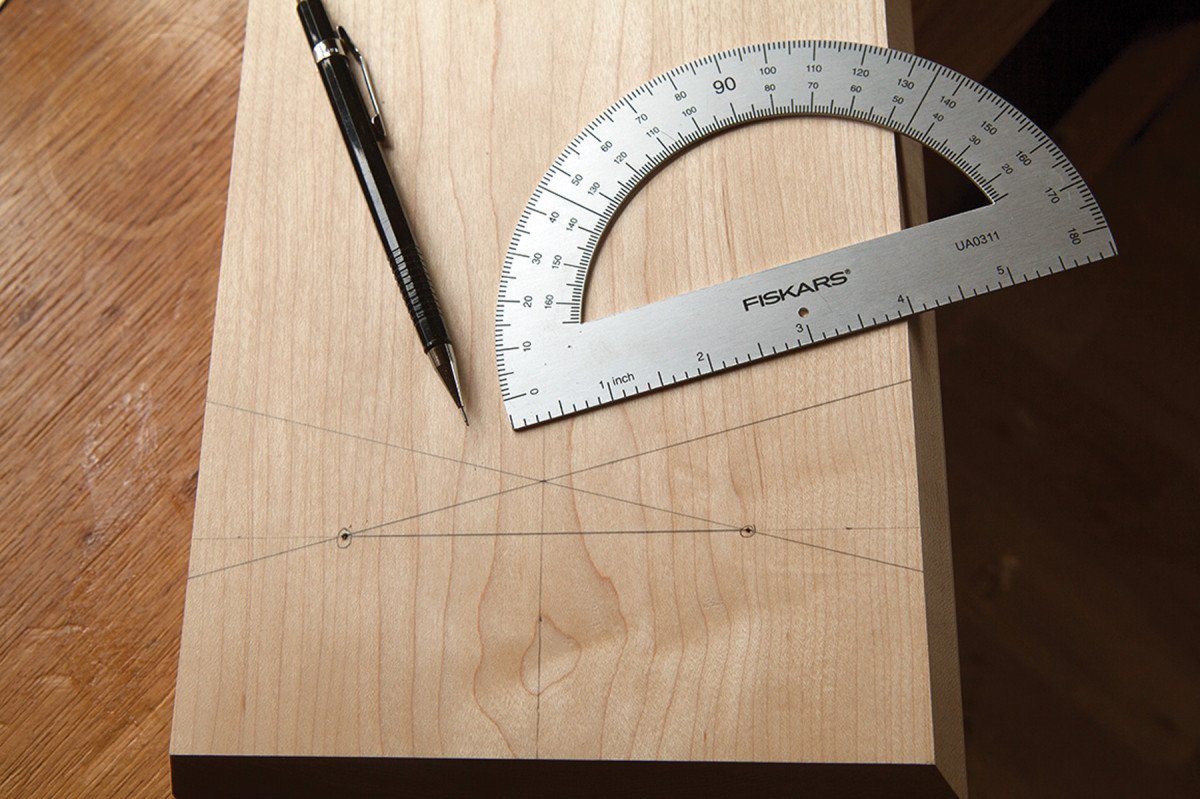

After laying out the mortise locations, draw a baseline that connects the two mortise locations at the front of the trestle top. Then use a protractor to strike a “sightline” from each mortise that is 14.6° off the baseline (study the photo below if you are scratching your head). The sightline is the pencil line that your bevel square will sit on as you bore the mortise.

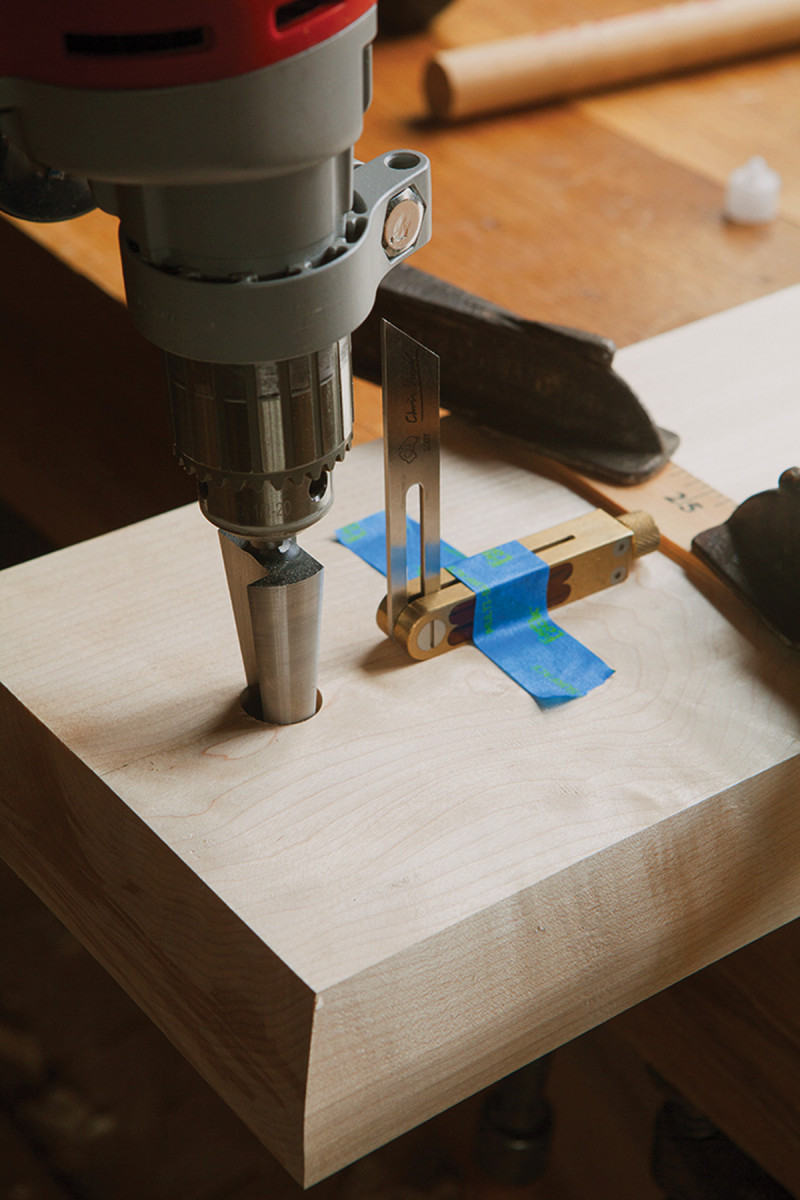

Set a bevel square for 15.5° off of 90° and tape its stock (handle) to your sightline. Chuck a 5⁄8” auger bit into your brace. You are going to drill a hole through the trestle top that is parallel to the blade of your bevel square.

Stand directly in line with the bevel square and put the tip of the auger on the mortise location. Tilt the brace to the same angle as the bevel square’s blade and crank the brace until the spurs are buried about 1⁄4” into the work. Stop and check your angle. Crank the brace a few more times and check your work, adjusting the angle as necessary.

Once you are about 1″ into the wood your angle is fairly locked. If you are off, don’t fret; you can fix that when you ream the hole to a conical shape.

Crank until the lead screw pokes out the other side of the board. Flip the board over and finish the cut by boring from the other side.

The single rear leg is simpler. The sightline is the centerline on the trestle top. Change the angle of the bevel square to 4° off 90° and tape it to the sightline for the rear leg. Bore the hole in the same manner as the front legs.

Trestle Table Cut List

No.ItemDimensions (inches)MaterialComments

t w l

❏ 1 Tabletop 11⁄43084Pine

❏ 6 Legs 15⁄8 15⁄830Maple

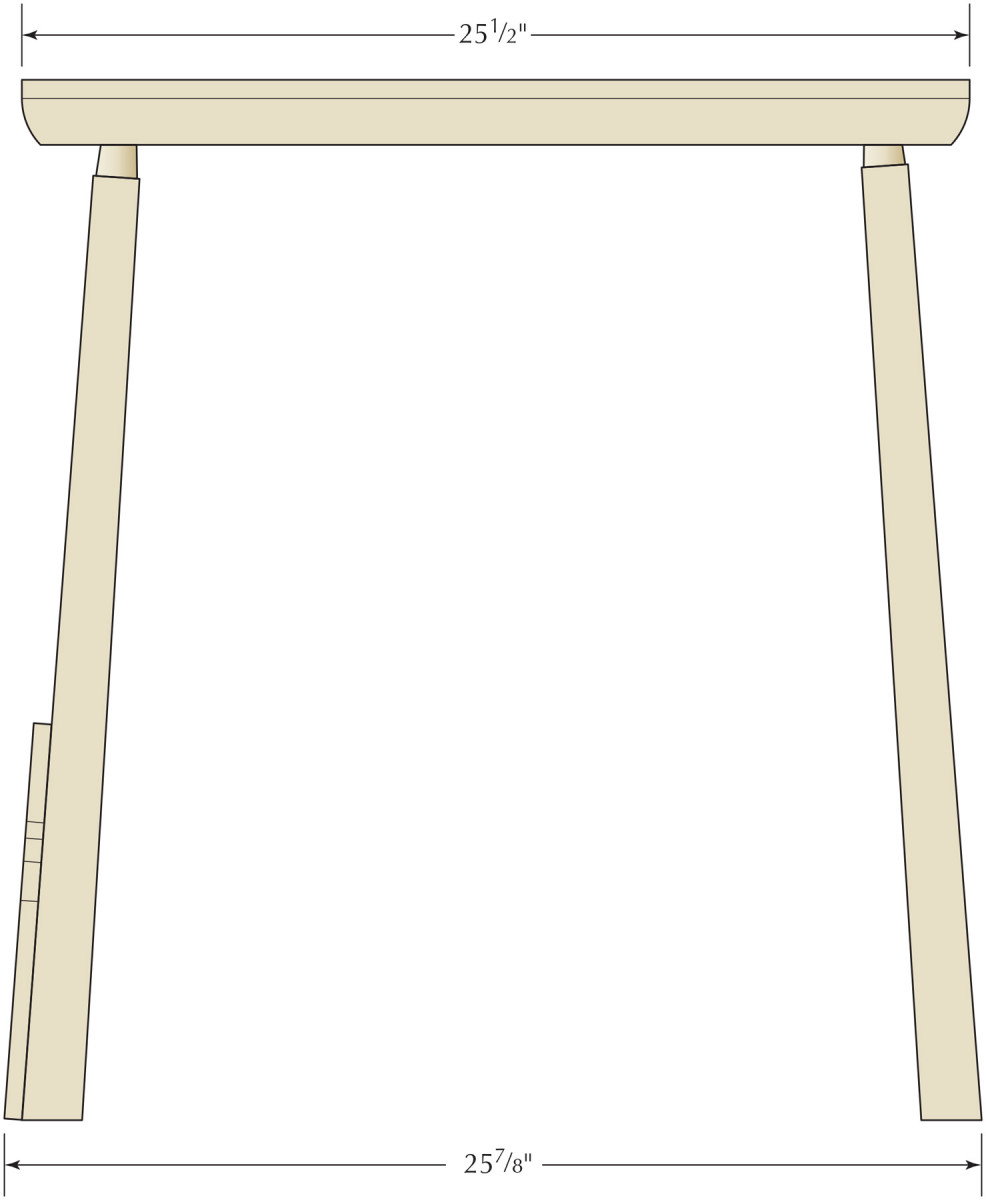

❏ 2 Trestle tops 13⁄8 8 251⁄2Maple

❏ 2 Decorative stretchers 1⁄2 20 131⁄2 Maple Oversized; cut to fit

Underside of trestle for leg layout

Elevation

Profile

Ream the Mortises

In line. Here I’m boring the rear leg. The centerline is the sightline. The bevel square is set for 4°.

Lee Valley makes an inexpensive tapered reamer that matches the angle of its tapered tenon cutter. This reamer can be chucked into a brace or an electric drill – I prefer a corded drill for the unfailing torque.

Some scholars have guessed that these conical mortises might have been burned to shape. While I like fire as much as the next overgrown boy, the tapered reamer is more predictable.

Ream & verify. After every four rotations of the reamer, remove the tool from the mortise and insert the dummy leg.

Before you ream the mortises, use your tapered tenon cutter to make a dummy tenon on a 1″ dowel. It’s easier to confirm the angle of your reamer by checking it against a cylindrical dowel than against a tapered leg.

Make small adjustments to how you tilt the reamer to correct the angle. Note that once you’re about 1″ deep, the angle is pretty much set.

Set your bevel square to the same angle you used for boring the 5⁄8” holes and tape it to the sightline. Ream each hole in short burst for better control. After four or five rotations of the reamer, remove the tool and place the dummy leg in the hole.

Ream the hole until the opening is 11⁄8” wide. You will be surprised how quickly this goes, so be cautious as you begin because it is easy to overshoot your mark. Ream all the mortises. Check your work by knocking the legs into their mortises and see if they line up like they should. If things are off a little, don’t despair; there is still another chance to make things look right.

Assembly

Clamped for success. The two clamps and flat board keep the front legs lined up during assembly.

The tenons are glued and wedged into the trestle tops. To make life easier, do these things before you slather the glue.

■ Trim the tops of the legs so they protrude 1⁄8” above the top of the trestle top.

■ Saw a 11⁄4“-deep kerf in the top of each tapered tenon. The kerf receives a wedge. The kerf should be perpendicular to the grain of the trestle top so that the wedge will not split the work.

■ Make some hardwood wedges with a shallow included angle – about 4° is right.

■ For each trestle, have two clamps and a flat board at the ready.

Upside down & backward. This looks odd, but it works quite well to get the trestles at exactly the same height. Clamp a pencil to the drill press table. Show the legs to the pencil.

If you are going to add a flat decorative stretcher to the front legs, you need to keep the front faces of the legs in the same plane when you glue up. That’s what the clamps and flat board are for.

Paint glue in the mortises and drive the legs into their mortises. Then clamp the front two legs into the same plane using the clamp and flat board. Don’t freak if this makes the legs a little cockeyed compared to the trestle top; it (probably) will not be noticeable.

Cut vertical. I find that I can keep the coping saw’s blade perfectly vertical if the work is horizontal and the blade is vertical.

Drive the wedges into the kerfs in the tops of the tenons. After the glue dries, trim the tenons and wedges flush to the tops of the trestle tops.

After assembly, you need to cut the legs to their final length and get the tops of the two trestles in the same plane. The easiest way to do this is with the drill press. Yes, the drill press.

Rasp horizontal. When I clean up the sawblade marks with a rasp, it’s easier for me if the work is clamped in a vise. Here I’m using a fine rasp.

The drill press has a table that is infinitely adjustable for height. I clamped a pencil to the table and cranked it so the pencil tip was 28″ from the floor. Then I turned the trestles upside down on the shop floor and rubbed the legs against the tip of the pencil. Simple.

Saw the legs to final length using a crosscut backsaw. Clean up the feet with a rasp or plane.

The Bottom Stretcher

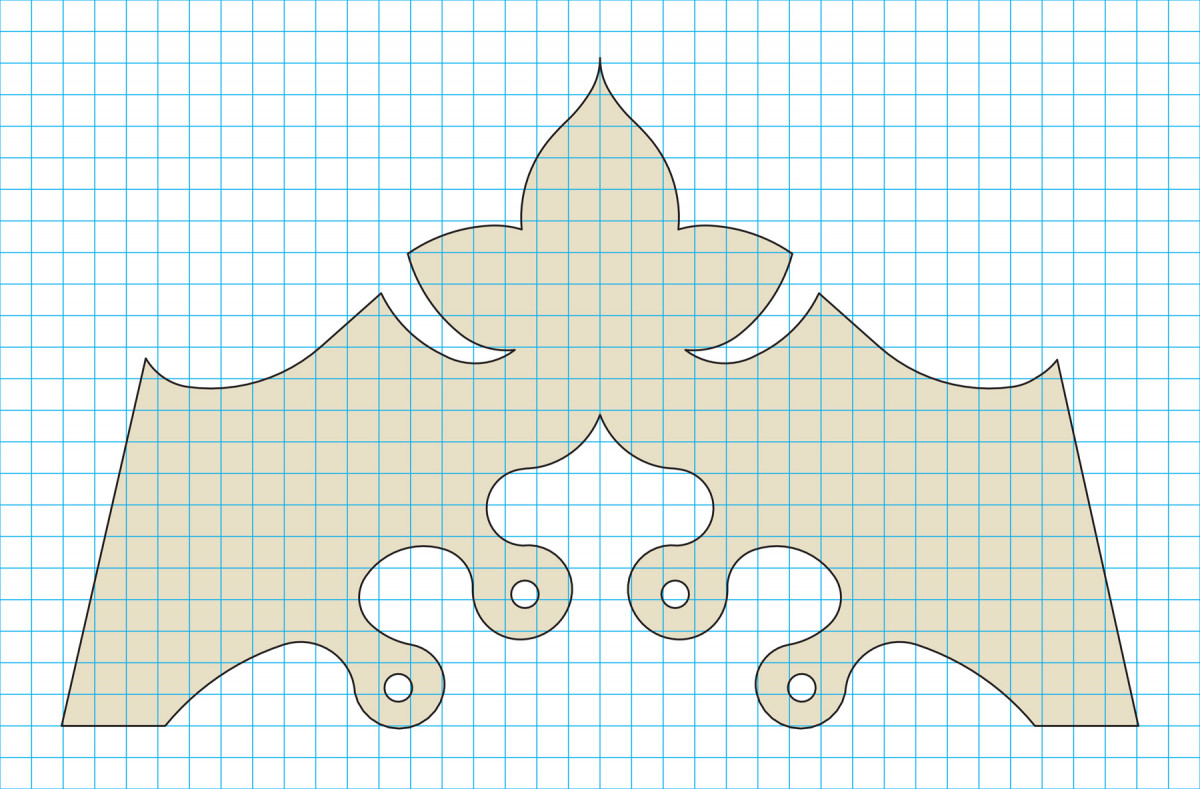

Stretcher Pattern One square = 1⁄2″ Note: This line depends on the final angle of your legs. Cut it square and over-wide at first.

The decorative bottom stretcher is a bit of a head scratcher. Should its grain run vertical or horizontal? I settled on vertical, which I think will make for a stronger trestle and make the decorative details less likely to snap off. I also think it is the best solution to deal with the wood movement of the stretcher and the trestle top during the long run.

Lay out the pattern on your stretcher panel and cut it to shape with a coping saw. Clean off the sawblade marks with a rasp.

The stretcher is both glued and nailed to the legs. I used 4d wrought-head nails from a blacksmith for authenticity. You can substitute cut rosehead nails if you are on a budget.

To attach the stretcher, glue it to the legs then trim away any overhang. Then lay out your pilot holes for the nails. Drill pilots and drive the nails in.

Decorative strength. The nails are as much for decoration as for strength. You can see them clearly in paintings of these tables from the Middle Ages.

If the flat and decorative stretcher doesn’t appeal to you, consider using a simple round one that is 3⁄4” in diameter with 1⁄2“-diameter tenons. You’ll need to bore mortises in the legs for this stretcher. But this is easier than you think.

To bore these mortises, you’ll need a 1⁄2” spade bit, a bit extension and a drill. Why a spade bit? It has a long center spur, which allows you some more room to steer in this application. Also, you can easily grind down the sides of the spade bit to make your mortise undersized if need be.

Chuck the bit and extension together and mark the dead center of the mortise on one of the flat faces of one of the legs.

Place a piece of tape on the spade bit that’s 15⁄16” from the spurs that cut the circumference of the hole. That will be the depth of the mortise.

Place the lead point of the spade bit on the centerpoint of the leg where the mortise will go. Rotate the leg a tad in the mortise so you are entering that face perpendicularly. Trust yourself a bit on this.

Line up the shaft of the bit extension with the marks for the mortise on the opposite leg.

Run the drill up to full speed without plunging into the leg. Once the bit is running at full speed, plunge slowly into the leg. Repeat the same procedure for the mortise in the opposite leg. Yes, it really is that easy.

Glue the stretcher in when you assemble the bases.

The Tabletop

Hot-doggin’. Line up the shaft of the bit extension with the lines you marked on the leg near the drill. That is all the accuracy you need to drill this mortise.

The top is merely a plank, usually about 5′ to 10′ long according to examples in paintings. I made mine 7′ long to fit the back of my truck so I could easily transport the table.

My top is three yellow pine 2x12s that are edge-glued. I left the underside rough from traversing it with my jack plane. I use this as a worksurface as things are much less likely to slide around. On the other face, I planed and finished the top smooth so it could be used for dining by merely flipping the worksurface over.

We have no way to know how these pieces were finished. They could have been left bare, oiled, waxed or painted. Some of the paintings show the tables as dark, which could be the wood, a pigment or the result of the smoky interiors of homes in the Middle Ages. In other paintings these tables look like they have no finish or a clear finish.

I used a homemade oil/varnish blend that I wiped on. The oil gave it a little color; the varnish gave it a little protection against spills.

The end result of this minimal finish is that the tables look shockingly modern, especially to people who don’t know they are forms from the 15th century.

While I expected the tables to look contemporary, I was shocked as to how useful they are in a modern, mobile society. I had planned on selling these tables to customers (perhaps some denizens of our local Renaissance fair), but they have become such a part of the fabric of our home I don’t think I can part with them. In fact, I’m now making another one these tables – this time with a maple top – to use as a desk in my new workspace. That top will get a traditional Danish finish made from soap flakes – a subject about which you can read right here.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.