We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

Three black planes on a dead man’s chest. Even the iron plane is thick with decades of tallow and oil.

Puzzling lubrication.

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in the August 2010 issue of Popular Woodworking Magazine

I ran out of mutton tallow this morning! I searched my tool chests, under the benches and in the drawers hoping to find just enough white magic to ease the passage of the big jointer plane up and down the long shooting board. But all the grease boxes were licked clean – the cupboard was bare. Must … find … tallow!

It was a set of smelly black British planes that started me down the slippery slope of the tallow trail. Unlike American planes, British planes are often black from ceaseless soaking in linseed oil and relentless rubbing with tallow – a practice that was perhaps not so good in the long run. Aside from linseed oil turning planes black with age and dirt, the royal armorers at the Tower of London have recently discovered that the walnut stocks of the Brown Bess muskets that they have been rubbing with linseed oil since the time of King George are getting a bit soft. They now recommend that you switch over to wax after 250 years or so.

Easin’ the Squeezin’

So we all know linseed oil, but mutton tallow was a mystery to me. In the old tool chest with the black British planes I found a tin of the slightly rancid white grease with the same smell that I had noticed on the planes. I tried it on the bottoms of the planes and was an instant convert. What a difference! All my effort was now going into cutting instead of overcoming friction. Tallow was the ingredient I had been missing.

Yes, there were other lubricants available in the pre-petroleum days, but olive oil, whale oil and beeswax were expensive and had better uses.

Besides, in the days before the cotton gin, your cloth was either linen or wool. Linen is made from flax, and pressed flax seed gives linseed oil. Wool comes from the outside of a sheep, and mutton from the inside. As meat, mutton was far cheaper than pork and beef in Europe, and the poor flavor of lamb fat made it unwelcome in the kitchens of France, and even in Britain.

So tallow was the joiner’s grease, and it was everywhere easing the labor of hand woodworking. George Sturt, in his memoir of life in a 19th-century wheelwright’s shop, described one of the workmen as having “a grease-box – that (also) hand-made – hanging amongst the row of chisels over his bench. But, come to think of it, every bench had this. A big auger-hole in a shaped-out block of tough beech served the purpose admirably. You could thrust your finger … into the grease-pot close at hand and easily take out grease for anointing both sides of your saw or the face of your plane.”

Aside from speeding your saws and planes, tallow-grease makes your spindles fly on the dead center of your lathe, it cuts the friction between the pad and the crank of your bit-brace, and it lets the wooden screws of your clamps and bench vises exert their maximum force. It keeps coping saw blades from grabbing and mortising chisels from snagging. Tallow makes metal screws turn effortlessly into the wood and lets grindstone axles roll freely in their bearing blocks. All of this saves endless elbow grease, but if that isn’t enough, the old blackened tallow-grease gathered from the trunnions of church bells was reckoned to have special curative powers when rubbed into the parts that ailed you. This may not be so, but you can quickly cure a chronically choking plane by a good rub in its throat with soft, slippery mutton tallow.

Oil & Water

Tallow is animal fat, and it’s slippery because the fat molecules, the triglycerides, are short, soft and round. When coated on steel, these molecules make a good protection against rust because they repel water. This quality becomes a problem, however, when it comes to gluing, for it is water that softens the long collagen molecules of animal glue and carries them into the wood. If enough tallow remains on the wood to prevent the water from penetrating, then the glue cannot hold. Still, it takes a lot of tallow to make a waterproof barrier on wood – you would almost have to do it deliberately.

Sometimes it is deliberate. Tallow rubbed on the corners of your door panels will keep any frame-joint glue that seeps in from getting a grip and causing your panels to shrink-split. Perhaps that was what young British apprentice Robert Simms was doing before he ducked out of the shop one day in 1922 to go buy a new saw.

As the salesman watched from across the counter, Simms examined the saw then gave it the standard test for quality. He bent the tip of the saw fully around to see if it would poke through the handle then spring back straight. His hands were still slippery, though, from his work in the shop and he lost his grip and the end of the blade sprung straight and slapped right into the salesman’s face. Being stiff-upper-lip British (and needing to make the sale) the toolmonger never let out a whimper. Bob Simms paid and ran.

So, where do you get tallow? It’s just melted fat and you can make it yourself. Ask the butcher to save some mutton fat for you – a lot easier around Easter time. Grind the fat and heat it, either directly in a pot or in boiling water. If you render it in boiling water the fat will rise to the surface and upon cooling you can lift it off in a cake. Reheat this and pour it through a sieve or cheesecloth. The resulting tallow will be much softer and may go rancid sooner than that melted out directly in a pot.

If you put the grease in a pot to melt without water, be careful of overheating and keep the lid handy to smother any flame.

Grease Box

A puzzle. The dovetail puzzle grease box.

Lid 1. The first lid swings aside, but the inner lid seems trapped by the dovetail …

Lid 2. … until you slide the inner lid back toward the screw. (The pivot hole is elongated.)

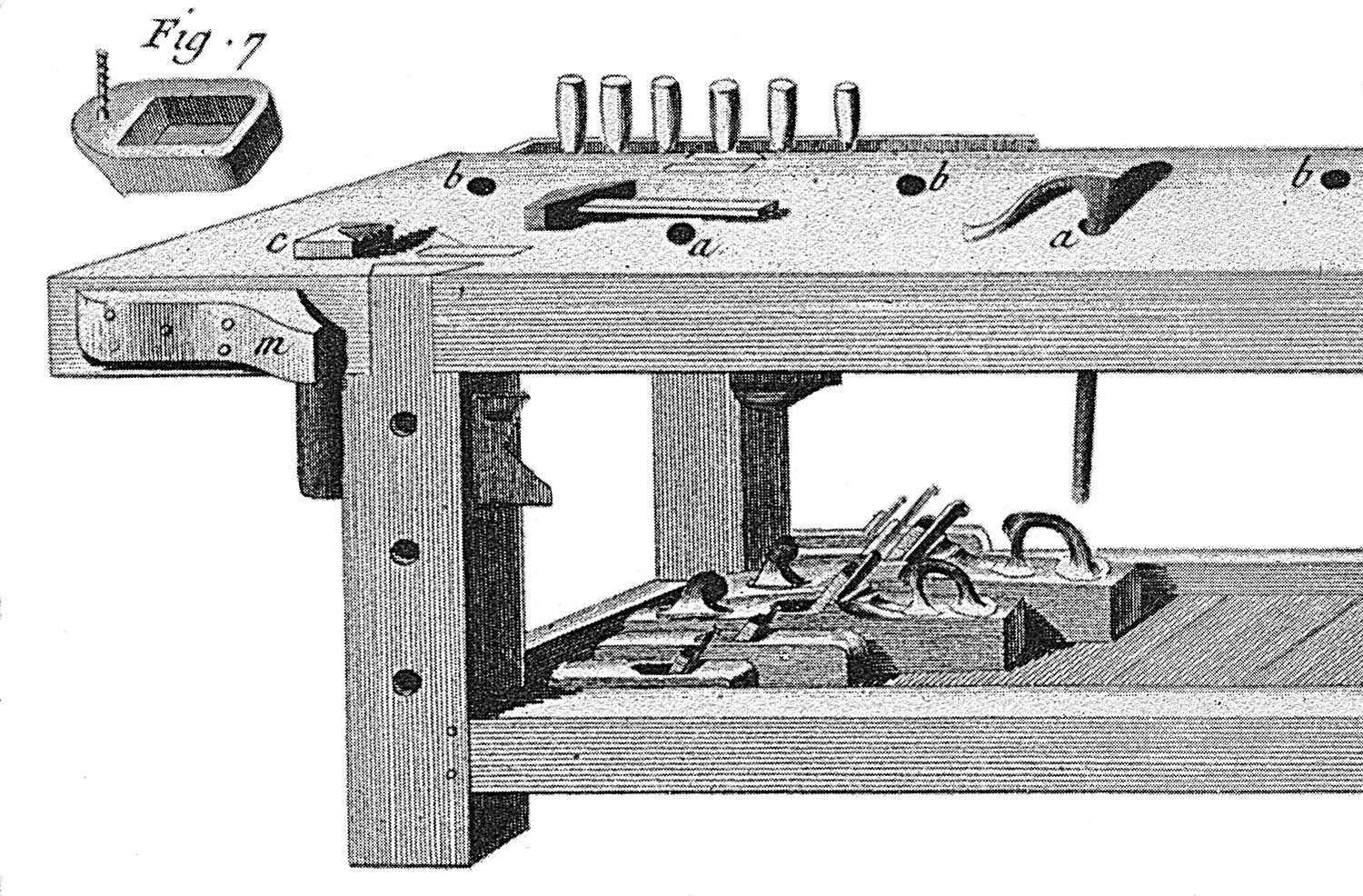

You’ll need a grease box too, because unlike beeswax, tallow can’t just sit around in a solid block. In “L’Art du Menuisier,” A.J. Roubo shows his workbench with a swing-out grease cup under the top, and this was common in most European benches. I use a little puzzle box with two lids. After the upper lid swings aside, you’re faced with a second lid that seems immovable. The upper lid conceals the fact that the screw hole through the lower lid is actually a slot that allows the lower lid to slide back free of the dovetail on the end and swing aside.

Roubo’s grease. André Roubo’s bench with the swing-out grease cup.

Yes, the tallow makes the tools work easier, but it was also a vital ingredient of a way of working that was visceral, muscular and organic. There may be synthetic substitutes, but I do like working in a shop where there’s nothing that would kill my dog if she ate it. So add mutton tallow to your tool chest and you will not only work like a classic joiner, you will smell like one too.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.