We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

When it comes to the history of woodworking, period furniture styles, and woodworking techniques, most woodworkers think about William and Mary, Queen Anne, Federal, Chippendale, and so on. It is arguable, however, that furniture as we know it would not be the same without Chinese furniture, and that studying Chinese furniture leads to lessons about woodworking techniques that are applicable to woodworkers today.

Historic Background

Figure 1. Examples of Ming dynasty furniture. This chair and incense stand have many of the typical characteristics of Ming dynasty furniture: clean lines, graceful curves, and a minimum of ornamentation. The use of curved legs as seen in the incense stand influenced the development of cabriole legs in Queen Anne furniture.

The earliest examples of furniture in China can be traced back to the Warring States (475-221 B.C.) and Han (206 B.C.-220 A.D.) Dynasties, where examples of lacquered furniture have been found in tombs from that time. The use of furniture began to expand over the following centuries, due to the Buddhist-influenced practice of formal sitting on raised platforms and low chairs. During the Northern and Southern Song Dynasties (960-1127 A.D.), tall tables and chairs become more commonplace. Artwork from that time shows furniture with some of the design elements typically associated with Chinese furniture, such as the waist found on Chinese tables.

Figure 2. Detail of huanghuali grain pattern. Huanghuali wood has a distinctive grain pattern. The pattern in the center is said to represent the face of a young girl. Pieces of wood that exhibited this pattern were highly valued, much like how tiger maple was desirable in western period furniture.

But it was really during the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) that Chinese furniture took on the form that we are familiar with today. Lines in Ming Dynasty furniture are simple and clean, often incorporating graceful curves into the design. There was a minimum of ornamentation, in order to allow the grain of the wood to speak for itself. One of the primary woods used during this time was huanghuali (“yellow flowering pear”), which has a pronounced grain pattern. This grain pattern was often incorporated in casework panels and chair slats as a way to best show off the pattern.

Figure 3. Ming dynasty cabinet, showing the grain pattern of huanghuali wood in the panels.

The transition from the Ming to the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) was accompanied by a burst of creativity in the arts. This was reflected in the aesthetic sensibilities seen in Qing Dynasty furniture. As opposed to the clean lines and forms seen in Ming Dynasty furniture, Qing Dynasty furniture is characterized by an explosion of detailed ornamentation, usually in the form of carved motifs and lattice work. It is worthwhile noting that the basic forms developed during the Ming Dynasty can still be seen underneath the often elaborate decorations applied to Qing Dynasty furniture.

Figure 4. Examples of Qing dynasty furniture. This round stand has elaborate carving over the surfaces, but on close inspection the forms of Ming dynasty furniture and joinery can be seen beneath the carving. It echoes the form of the Ming dynasty incense stand in Figure 1, but has much more elaborate carving over its surface.

During this time in Europe, there was a growing fascination and appreciation of Chinese art forms, including ceramics and furniture. This interest in Chinese design and aesthetics was strongest in England. The lightness and graceful lines of Ming Dynasty furniture also found their way into western furniture as can be seen in the transition from the relatively heavier styles of the William and Mary period to the Queen Anne period. Appreciation for Ming Dynasty forms can be seen by the incorporation of curves into Queen Anne furniture. The cabriole leg often seen in Queen Anne furniture is clearly derived from the curved leg forms found in Chinese furniture.

Figure 5. An example of a Queen Anne chair. The slat in the back is derived from the backs of Ming dynasty chairs, while the cabriole legs echo the curves found in pieces like the incense stand in Figure 1.

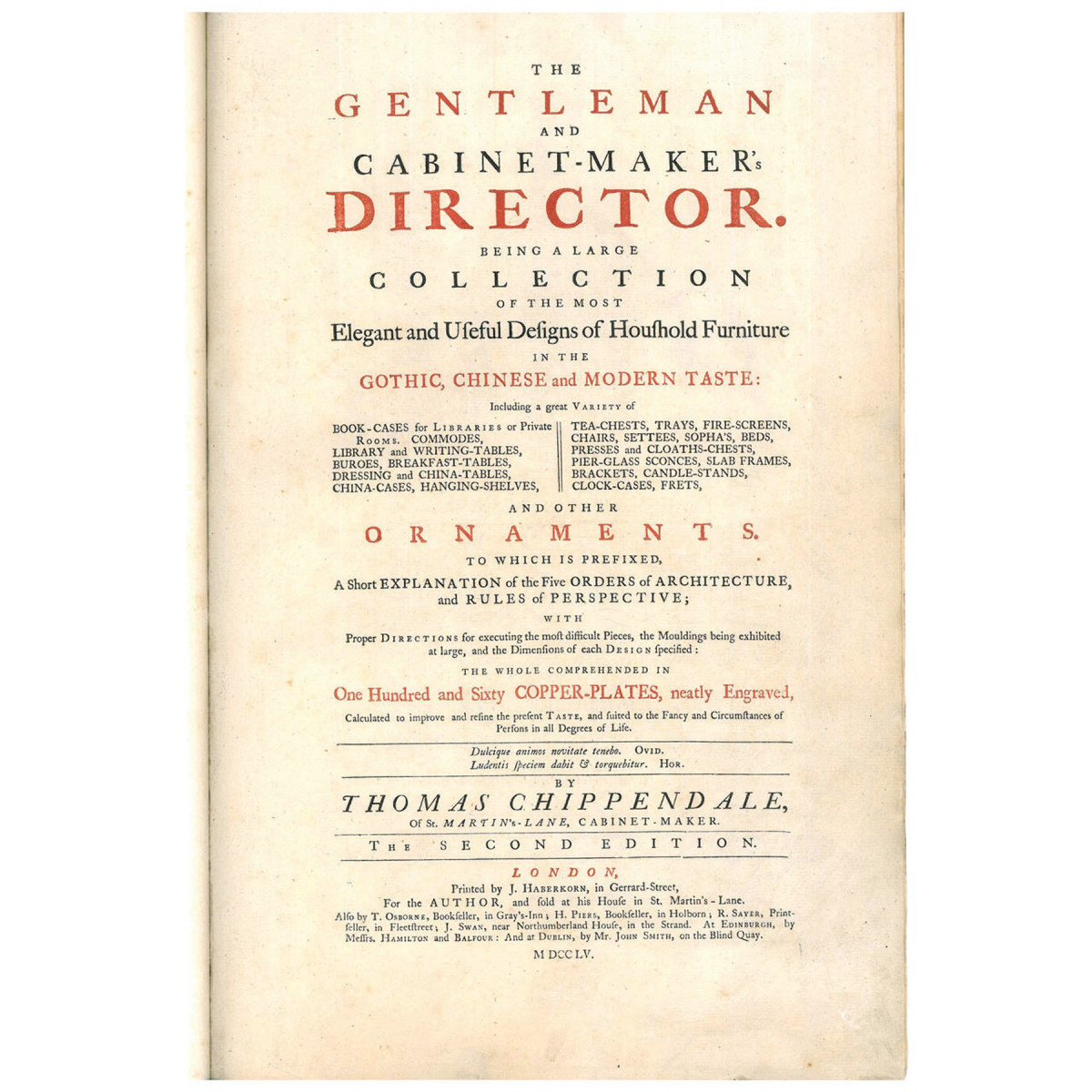

Designs from Chippendale and Hepplewhite are near-direct descendants from Chinese forms. In fact, Thomas Chippendale’s famous catalog, “The Gentleman and Cabinetmaker’s Director” is subtitled, “Being a Large Collection of the Most Elegant and Useful Designs of Household Furniture in the Gothic, Chinese, and Modern Taste”. It’s not an overstatement to say that without the influence of Chinese designs, western period furniture would not look the way that it does.

Chinese Furniture Elements

Figure 6. Chippendale thought that Chinese furniture was not necessarily a bad thing.

Ming Dynasty furniture represented a great leap forward in the development of Chinese woodworking. This was the period in which the more complicated interlocking forms of mortise and tenon joinery was developed. Although an overview of the many different interlocking joints used in Chinese furniture is outside the scope of this article, an example of an interlocking joint used to connect the leg and apron of a table can be seen in Figure 7.

Figure 7. An example of an interlocking joint found in Chinese furniture. This joint would have been used to connect a leg piece to the apron of a table.

All of the pieces interlock to create a seamless joint.

This was also the first time in Chinese history where the design of the furniture also reflected its function. For example, the arched arms of a Ming Dynasty chair don’t just drop gracefully downwards from its midpoint just to look nice. The angle of the drop matches the natural fall of a person’s arm from the shoulder down to where the hands rest on the ends of the chair’s arms (Figure 8).

Practical Lessons from Chinese Furniture

Figure 8. In this Ming dynasty chair, the fall of the arms is deliberately designed so that it follows the natural fall of a person’s arm from the shoulder, as can be seen in the side view.

It might be asked why Chinese woodworkers developed the complicated joinery typically found in Chinese furniture pieces. I think the most likely reason is that it solved a woodworking engineering problem. The woods used in Ming Dynasty furniture came from a variety of tropical species. As mentioned above, one of the most popular woods used during the Ming Dynasty is huanghuali, which is a member of the rosewood family. Other woods used include red sandalwood, rosewood, and ebony, all sourced from Southeast Asia.

Being tropical woods, these woods contained oils and resins that would interfere with gluing. Not much is known about glues used in traditional Chinese furniture making, but during that period of time (1300-late 1500’s), hide glue (or some other animal-derived glue) and rice glue would have been the only choices available. Given the glue choices of the time and the woods used in Chinese furniture, it is doubtful that glue would have been a reliable method of keeping joinery in place.

This may explain why Chinese woodworkers went to the trouble of making the elaborate interlocking joints found in Chinese furniture. Given the climate of China, and the lack of controlled interior environments during the Ming and Qing dynasties, Chinese furniture would have been subject to large humidity swings, and so glued joints would have ample opportunity to fail. Frame and panel construction would mitigate many of the problems with wood movement, and the elaborate, mechanically interlocking joints used to join the frame elements together would take care of the glue problem.

Frame and panel construction also solved one other design issue that Chinese furniture makers had to deal with. The lumber obtained from the tropical species used in Chinese furniture making came from logs that were relatively narrow in diameter, because the trees were so slow growing. At most, these logs would be 10” in diameter. In addition, the logs often had a good part of the center that was rotted away, or otherwise unsuitable for furniture making. To get a board 8” wide from these logs was doing pretty well. In my trips to China to look at furniture, I rarely saw a board that was much wider than 8”. So how do you create a tabletop meant for dining out of huanghuali when the widest board you have is 8” long, and glue is unreliable? Use frame and panel construction.

Examination of Chinese furniture pieces (Figure 9) shows that this approach, while certainly more time consuming than a straightforward glue up, can be extremely successful. I have seen a good number of tables made with frame and panel construction where the lines between the panels and the frame are incredibly tight, on the order of 1⁄32“, despite the fact that these pieces are around 500 years old.

Go See it for Yourself

Figure 9. The top of this Ming dynasty table is made with frame and panel construction, probably due to the limitations of the width of boards available to Chinese woodworkers from the trees that they harvested, and the inability of glues available at the time to adhere to rosewood species.

Most museums with a furniture collection will have at least a few Chinese furniture pieces to examine. Museums that I have personally visited that have good examples of Chinese furniture include the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City. The Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, just outside of Boston, has the Yin Yu Tang exhibit, which is a 200 year old Chinese house that was brought to the U.S. and reassembled, and is a great way to see Chinese furniture in the context of the buildings they were used in.

Even though this piece dates back to the early 17th century, the joints remain impressively tight.

If you happen to be in China, in Beijing, there is the National Museum of China, which has a large collection of Ming and Qing Dynasty furniture. There is also the China Red Sandalwood Museum, which has a tremendous collection of Ming and Qing furniture, as well as some very well done replicas. In Shanghai, the Shanghai Museum also has a good collection of Ming and Qing Dynasty furniture.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.

Excellent, well-researched article! I had some knowledge of traditional Japanese joinery, and a reasonable understanding of western furniture traditions, but I had never seen the connection to traditional Chinese furniture. Wonderful to learn this aspect of our shared history!