We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

Using your hands to sketch can teach your eyes to really see.

Most of us use our eyes to avoid bumping into things; we probably are only using 20 percent of our visual ability. I had a student some years ago at Rowden Workshops who had a history in the special forces. “I’ve never drawn in my life,” he said in a deep, dark, threatening voice. Yet within six weeks he was a highly competent draftsman, putting down accurate lines that described what he was looking at. His visual accuracy was trained on the battlefield. He had used his eyes to stay alive.

Twenty Minutes a Day, Four Times a Week for 50 weeks

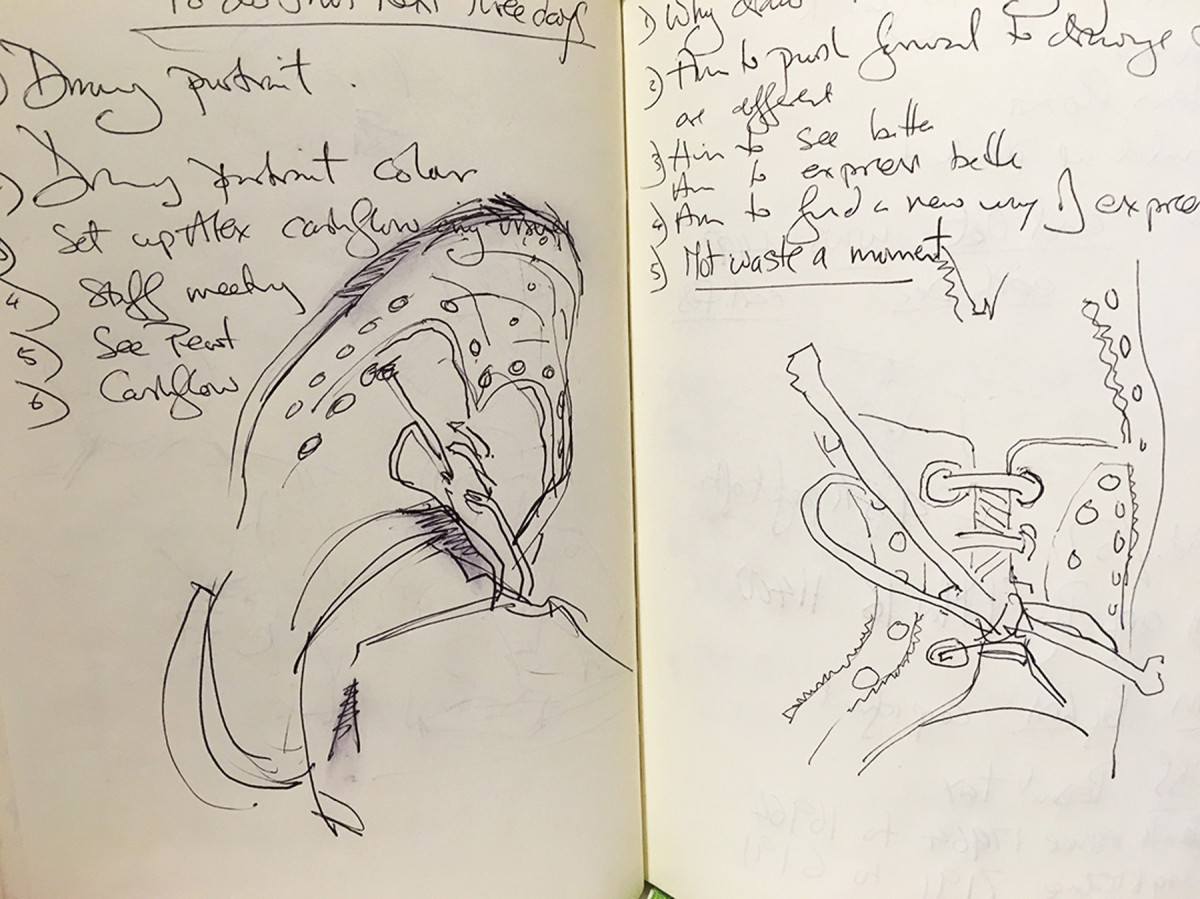

Sketching notes. A notebook goes everywhere with David Savage, who insists that students learn drawing as part of their furniture making courses at Rowden Workshops, his Devon, England, school. While waiting for a doctor’s appointment, he wrote a job list and sketched two drawings of his right shoe. Don’t wait to draw special stuff, teaches Savage. Just draw what’s there.

All of us can learn to draw. We all have the ability. What we need to understand is that to do this as woodworkers we do not need to draw like Leonardo da Vinci. We need to draw just well enough to put the image down.

I ask students to give it 20 minutes of good time per day four days each week, during their time at Rowden. It’s not hard, but it is demanding. Like going to the gym, it gets easier and more rewarding as you do it. It is important but never urgent – so you need to make it a part of your planned day. If you don’t, that urgent sanding or dovetailing will always get done; drawing won’t. Which is stupid.

Why Bother

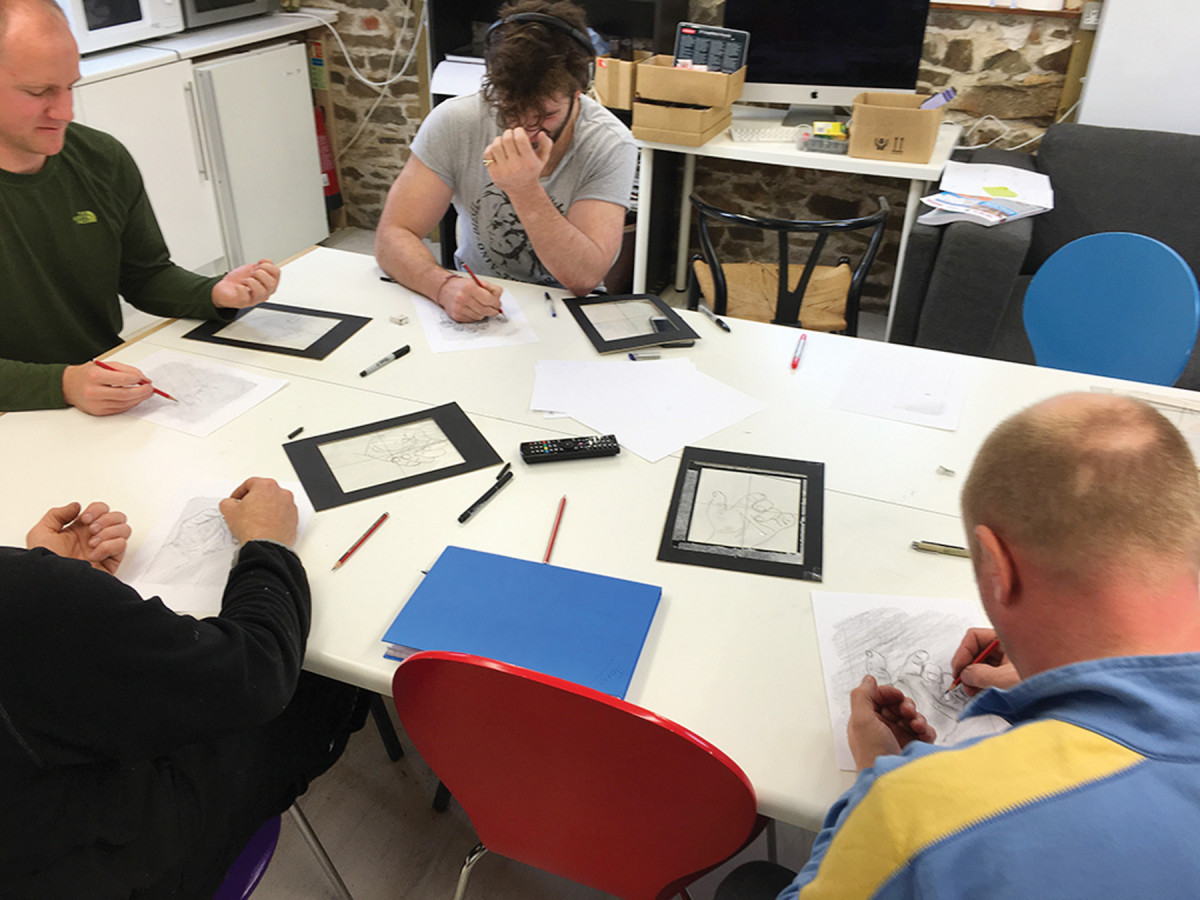

Yes, you can. These four guys have just started at Rowden, and are each drawing their left hand. Note the frames of clear plastic that have been used to rest on the left hand as an aid to get the drawing going. We have a series of exercises that overcome the “I can‘t draw” mindset.

It’s about making something worth making. You might cut lovely dovetails, but is the piece in proportion? Does it look good? Will someone 100 years from now say, “that’s nice,” or did your piece go in the dumpster 50 years ago? Drawing is about your response to the patterns of nature. Seeing things – really seeing things – not just taking phone shots and putting them on Instagram. Drawing allows you to make better visual judgements when planning your piece of work.

Surround yourself. This is a typical student bench area at Rowden (former student Paul Chilton is pictured). I encourage you to hang your drawings as you do them. This helps you to see them objectively. In a folio, they are out of sight and out of mind. Surround yourself with your drawings; that way you catch them in the corner of your eye, and can really see what is good and what needs work.

Drawing is going beyond “the golden section” and conventional proportioning systems and going to the essence of how they were developed. Drawing takes you to seeing the patterns and essential structures of nature. It enables you to build your pieces “in tune” with nature, not at discord.

Get Started: 8 ‘Rules’

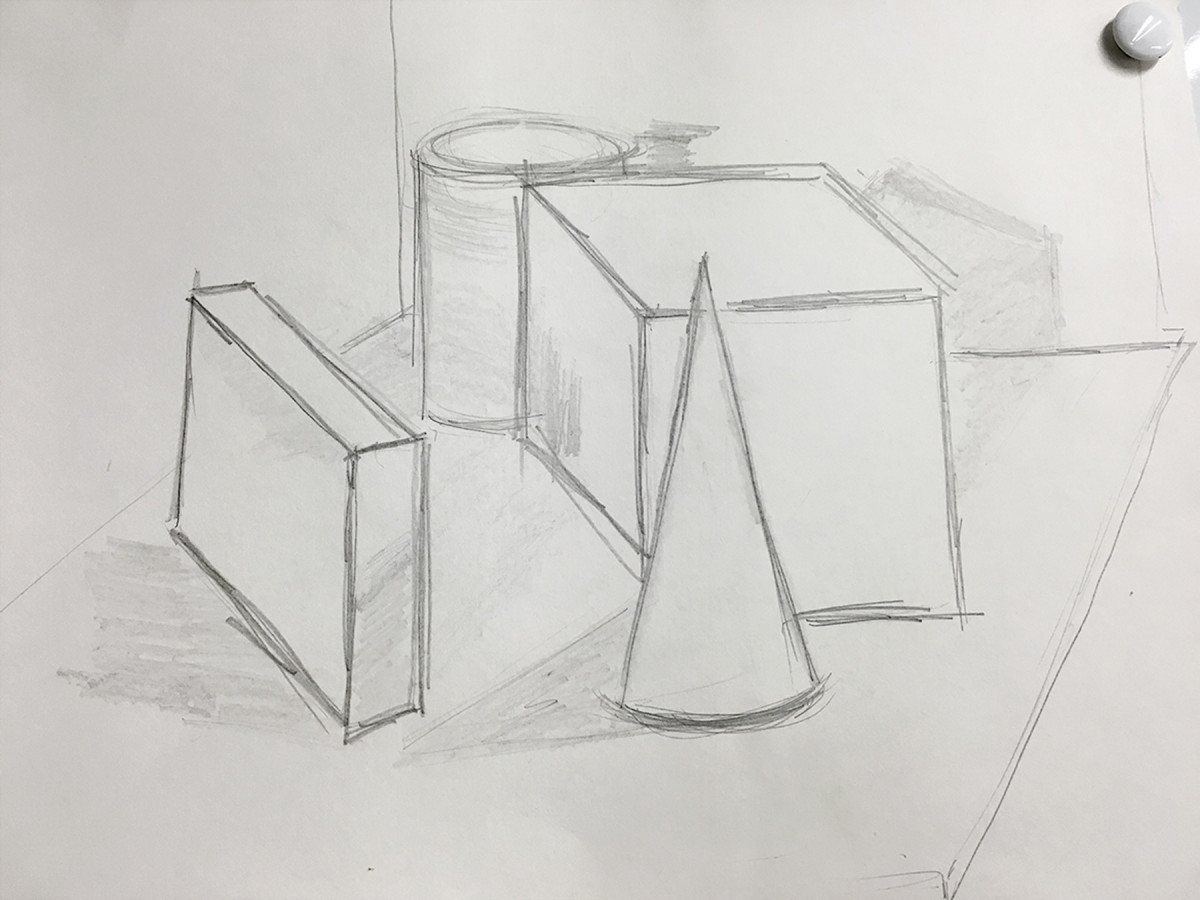

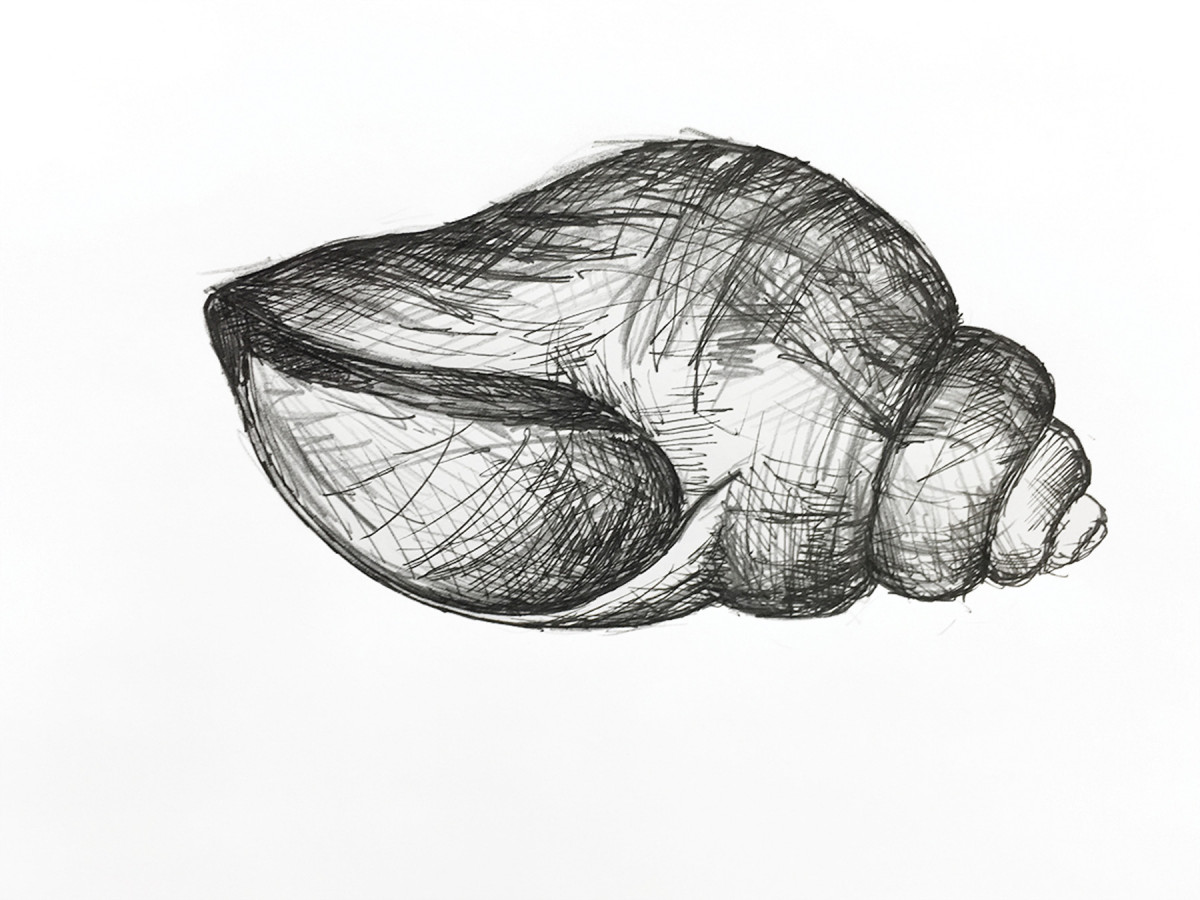

Where it starts. Just use your eyes to look hard and give me a dozen really honest lines that are in the correct relationship to each other. Keep your head in one place. The objects do not move and there is no color. All you are looking at –and drawing – are the edges.

1. Remove from your head all “non visual thoughts”

2. Silence is great

3. Sit down; this puts your head in one place

4. Use a support (such as an easel) to hold your pad or sheet of paper vertically along side the object

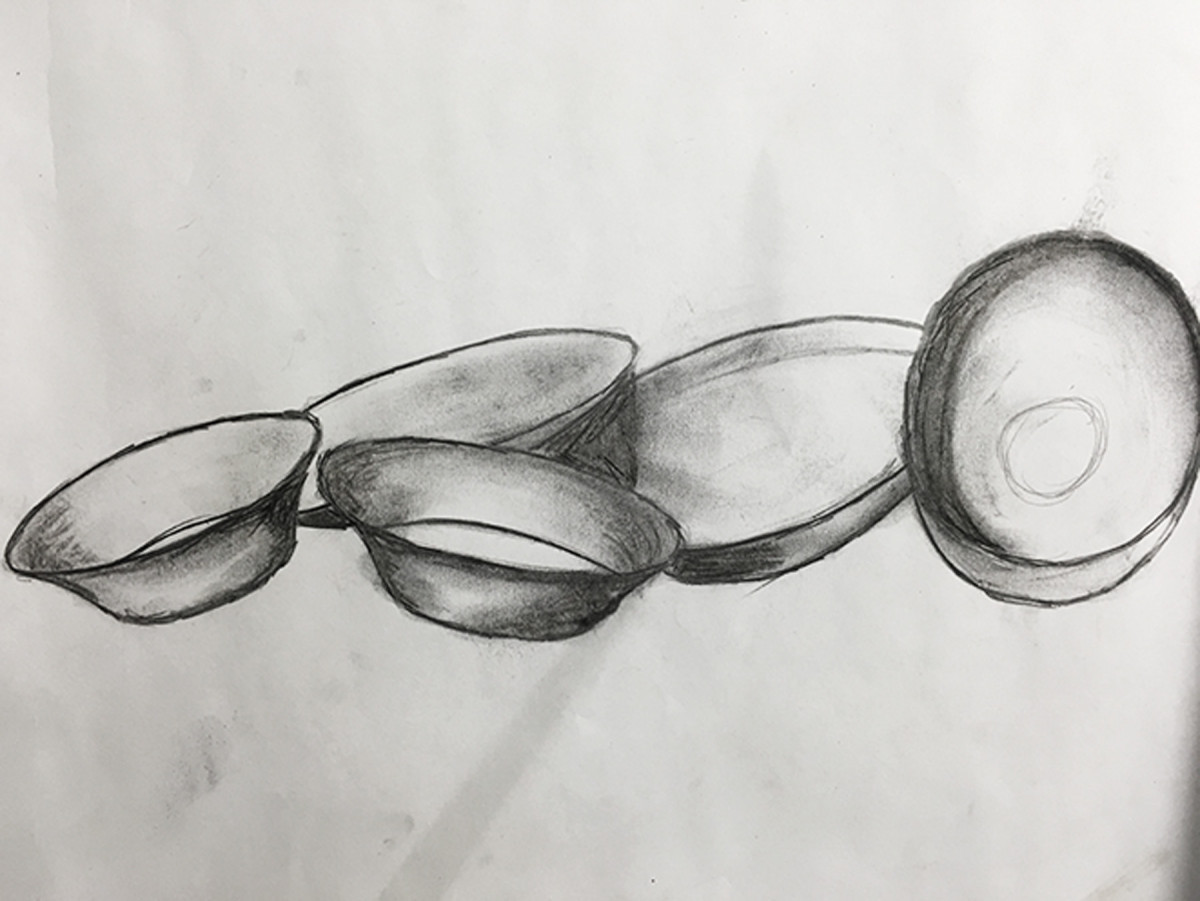

Next step. Give me circles. It’s like stirring a cup of coffee, but with a pencil. Now add tone; this is light and dark to express volume.

5. Draw “sight size”; that is, the same size on your page as the object in front of you appears

6. Choose a simple form to start with; we use a white cube on a white ground

7. Look very, very hard at the object

8. Draw honest lines where the edges are

Seeing Better

Eye for accuracy. Accurate work demands that you open your eyes and really see. Drawing helps you do that. Here, Steve Hickman is perfecting large dovetails.

Seeing better is what happens when you draw. You come out of a life drawing session and go home, all the colors of the fields are vivid and sharper, much more than before the class. Drawing is a process of filling up your visual vocabulary, assembling a set of images, shapes you like – anything from sea shells to a sunset, from the way a leaf joins a twig to the way water flows over a beach. All are gathered into your personal visual language. Again taking photographs doesn’t do this; it shows your interest, but it is outside your mind, still not a part of you.

Like learning language, you need to gather the parts that make up language – the visual equivalent of syllables and words – and put them in the back of your head. That’s where they live. I call it “uploading.” You upload when you sit and draw an object.

Like learning language, you need to gather the parts that make up language – the visual equivalent of syllables and words – and put them in the back of your head. That’s where they live. I call it “uploading.” You upload when you sit and draw an object.

I tell students to not wait for significant objects; just draw the damn teacup on the bench. Mundane it may be, but you will soon find visual interest in the shadows, in the way the handle joins the body. You will start to really see that teacup. Upload four times a week, every week, and you will start seeing stuff when you go out. You start bringing stuff back to draw, you start drawing your left foot when sitting waiting for a doctor’s appointment. Now your eyes are working for you.

Personal Visual Language

Nineteen-year-old Josh Reynolds (namesake of a former president of the Royal Academy), is doing everything right to put down a solid personal visual vocabulary.

It is personal – powerfully deeply personal. These are images gathered over years to form your individual visual vocabulary. Unlike most ideas that disappear with saddening ease, these are ideas that stay with you. Like a stick stuck in the ground 30 years ago, when you did that quick drawing – five honest lines. Now you go back, dig under the stick to find the original image. The original idea. Still there bright and shiny and complete like buried treasure.

Fail to draw and your ideas will not stop coming, but they will tend to disappear with the morning mist. Nail them down immediately; drawing five honest lines will install the image in your memory system. Thirty years later when you need that idea you “download” it and it pops of the end of your pencil.

Patterns of nature. What is essential to good creative expression is that we see and understand more of how nature creates her own patterns. We do this by looking very hard, by drawing. This is also a part of the work in developing your own visual vocabulary.

This is the creative bit; having put stuff up there in the back of your head you can draw upon it. Notice the language. Sit with the problem and just draw. Be uncritical, just see what pops off the end of the pencil. Paul Klee called it “taking a line for a walk.” Just doodle. If you have done it right something will come pretty quickly. At Rowden, we have a two-week gap between getting the brief and doing the doodles. That allows the brain a time for “unconscious scanning.” Your first ideas will probably be from the front of your head, the area of conscious thought. Those ideas might be OK, but dig deeper and you get to the gold.

Royal Academy Schools. This is where I learned to draw – the life room at the Royal Academy Schools in London. It’s the oldest, and in my view still one of the best, art schools in the world.

These are the ideas you uploaded years ago; it takes the filing system in the back of your head a while to get to them. A second day at the problem will usually drop ideas off the end of your pencil that will surprise you.

But the brain works a bit like a computer. Rubbish in, rubbish out. It demands that you put down a powerful vocabulary of strong visual images to draw upon. Then all sorts of new and interesting ideas come together.

So that is why. There is no way that gathering images in Instagram or Pinterest will work the same way.

Visualization. Life drawing helped student Rob Newman develop his ideas he as designed this prototype for a new table.

We see student pieces in exhibitions every year sourced crudely from other people’s work – the top of this man’s table with legs from that woman’s table. Digital photographs are great tools, but they are external. Drawing is internal.

CAD is a great tool in the process of developing an idea, but it is fundamentally uncreative. I have a friend who works in the Audi design center; she tells me all the concept work there is still paper and pencil. The great architect David Chipperfield has a studio marked with an absence of computer screens and an overwhelming presence of models of buildings being developed in a series of iterations.

At Rowden we would not employ a maker – however competent – without decent drawing skills. Drawings show they have “good eyes,” and as a consequence he or she is much easier to work with.

How to Start Drawing

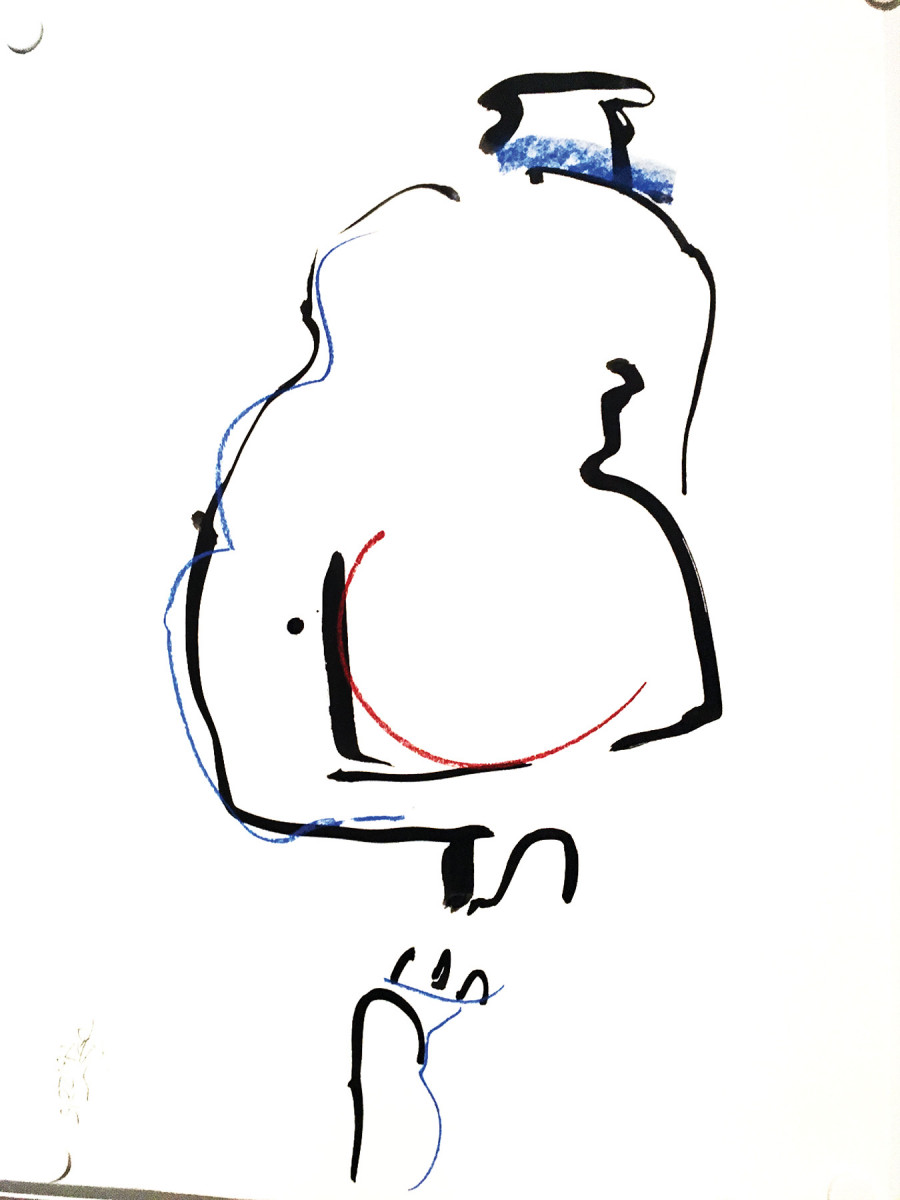

Life drawing. We teach life drawing for all but the very new students; understanding the human form is one of the most visually nourishing activities you can do. Students take from this hour a memory of balance, of how a knee or ankle joint actually looks and works. Patterns of nature. The guy at the far left back is “sighting” – using his extended arm and pencil to measure and compare distances on Amanda, the model, and on his drawing.

Getting started on your own is not easy, but it can be done. You just need a plan. Betty Edwards’ book, “Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain” is a good plan to follow. We use some of her exercises at Rowden.

Do as I do. I lead by example and do life drawing every other week as an exercise in looking.

The essence of doing this to do little, but often. Starting is always the hardest part. I go through a series of things that I call “othering.” I turn off the news. I shut the phones off. I sharpen five pencils and put some music on. All this prepares my visual mind to start work. I shut down the right side of my head. All the command centers of control, mathematics, language, rational thought, get put to sleep.

Progression. Rose Carter-Stouts is a former student and is now an intern, helping new students and developing her own work. Her bench area displays her range of drawings.

You do need to control your thoughts when drawing. The major control center will not find it comfortable at first. That part of your brain is used to providing you with quick visual symbols of things: “Don’t bother looking at that bicycle; I have a symbol of a bicycle already – here you are.”

I set up a drawing session once with students ranged all around a bicycle. One guy was looking right down the side of the bike; all he could see was the tire and handlebars. What he drew was not what he saw, but a full-on side view of a bike. This was the symbol of a bike his left brain provided him with. Shut this side of the brain down; the visual holistic and music centers of the brain are all in the right side of the head. Let them work.

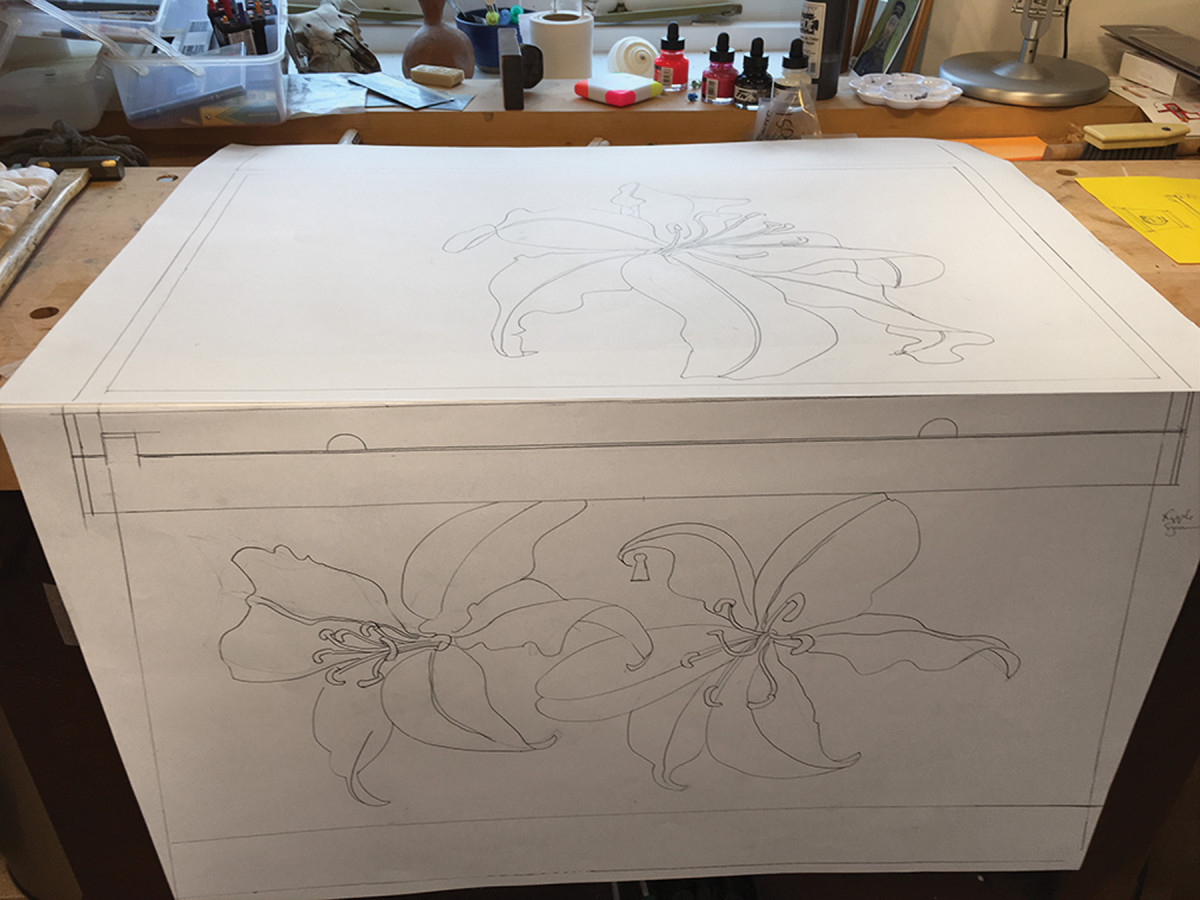

My space. This is my personal workspace, with my bench, tool chest, recent life drawings and a full-size drawing of a marquetry project, which will incorporate lilies in ripple sycamore with rosewood stamens on a poplar veneer background. It will be part of a chest based on Christopher Schwarz “Traveling Anarchist’s Tool Chest.”

Start simple and sit down as you draw; this keeps your head in one place at one height. Drawing a white cube and rectangle on a white background – just the outlines, well observed. Honest well-seen lines. The first time, a good hour looking very hard will exhaust you. With a few weeks of consistent work you should be banging those lines down with the confidence of an expert.

Move on to curves and circles. Drawing an ellipse is like stirring a cup of tea. You need to practice the hand, wrist and arm movements necessary to put the line where you want it. The pencil is the Ferrari of mark-making tools: light, fast, agile. But you need to acquire the skill to drive her, or she will kill you. Like using a chisel, it’s a skill.

Move on to curves and circles. Drawing an ellipse is like stirring a cup of tea. You need to practice the hand, wrist and arm movements necessary to put the line where you want it. The pencil is the Ferrari of mark-making tools: light, fast, agile. But you need to acquire the skill to drive her, or she will kill you. Like using a chisel, it’s a skill.

Drawing is not just for woodworkers but it does make us all better makers. And you can learn it. I boasted once that I could teach a house brick how to draw; that was a vain boast. The house brick has to really want to learn to draw.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.