We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

Here is a question that has been going through my mind for more than a decade: When an 18th-century French woodworker started building a workbench, what was the moisture content of the wood? Had it been seasoned for many years? Freshly cut? Something between?

Lots of modern people have speculated about the answer, but I have yet to find an historical source that answers the question to my satisfaction.

A.J. Roubo doesn’t mention the moisture content of the wood for a workbench in “l’Art du menuisier,” his 18th-century multiple-volume masterpiece on the craft. In reading over Roubo’s section on the bench, here are the parts that mention the wood and its qualities.

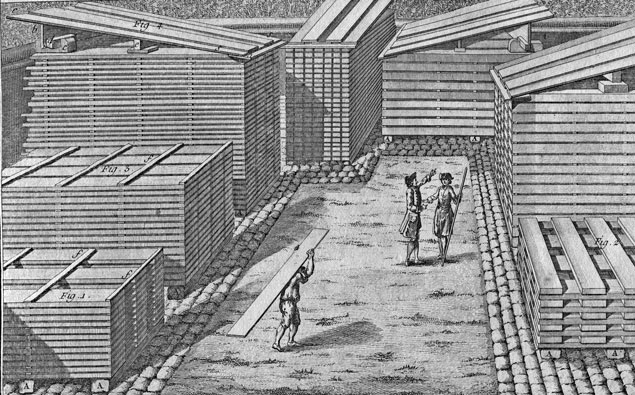

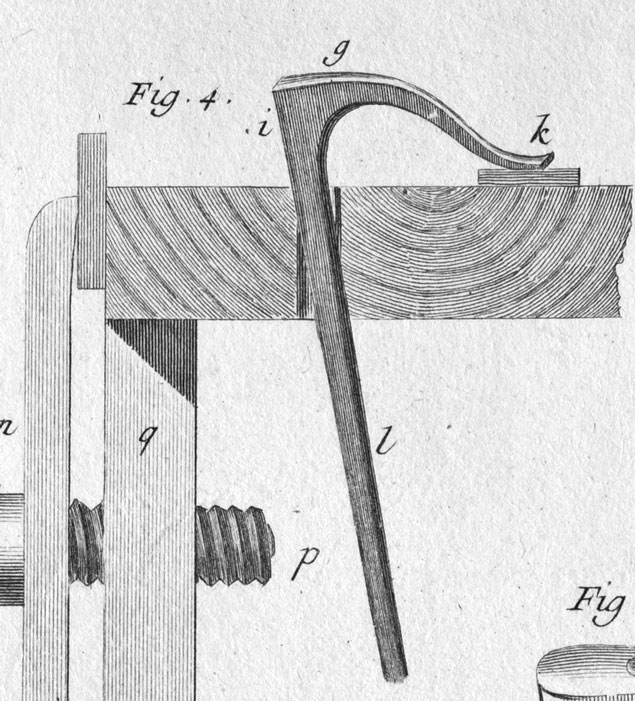

“The workbench is the first and most necessary of the woodworking tools. It is composed of a top, four legs, four stretchers and a shelf. The top is made of a plank or table of 5-6 thumbs thickness by 20-22 thumbs in width. For its length, that varies from 6 to 12 feet, but the normal length is 9 feet. This bench is of elm or beech wood but more commonly the latter, which is very solid and of a tighter/denser grain than the other….

“…The planing stop should be 1 foot in length at least, and be of very hard and dry oak so that it can withstand the mallet which one is obliged to hit it with to make it move…

“…The legs of the bench are of hard oak, very firm, 6 thumbs in width by 3-4 in thickness….

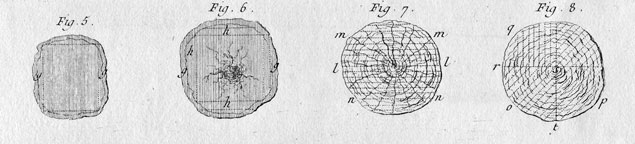

“…One should observe also to put the heart-wood side of the bench on top because it is harder than the other, and if the wood experiences dimensional changes, it is more likely to change from this side rather than shrinking from the other side.”

To be certain, Roubo discusses the seasoning of lumber for furniture, but as anyone who has dried thick slabs can tell you, those are an entirely different animal from lumber used for tables and chairs.

While reading the rest of Roubo’s writing on furniture, a section on kitchen tables stuck out. Here is some of the text from Plate 253:

“The top of kitchen tables is made of a thick plank of beech in which you assemble the legs whether by tenon and tail like the woodworkers’ workbenches, or even with double assembly, which is about equal. In either case, it is good, for cleanliness sake, that the assemblage/joinery not pass through the top (so that they [the tops] be easier to clean and straighten up as you are using them), but on the contrary that they have but two-thirds of its thickness, which is sufficient, always with the condition that they be assembled very exactly.

“Kitchen tables vary from 6 feet up to 12 and even 15 to 18 feet in length by 18, 24 and 36 thumbs in width, but this is very difficult to find without splits and other defects.

“The thickness of these tables varies from 4 to 6 thumbs and even more, if possible, the large thickness being necessary given that you flatten them from time to time, which thins it rather promptly.

“In general, the top of kitchen tables should be oriented in a manner such that the heart side is on top so that when the slab is moving [in response to dimensional/seasonal change], it can only move from this side, which you can remedy easily. What’s more, you can eliminate this problem, as least partly, by choosing the driest wood possible, which has but a very little reaction as a result.”

Here Roubo is saying to make kitchen tables like a workbench. And to use the driest wood possible. And to orient it heart-side up. Here’s another clue:

“Whether the kitchen tables be wide or narrow, it is good to place across the two ends some [leather] straps [it is a ligament from an ox, dried and hardened] attached above, which prevents them from opening, but restrains them, which is much better than putting there iron links, which, truthfully, prevents their opening, but which, when the tables shrink, splits them, given that they do not make allowance for this.”

The way I read this (and I could be wrong), is that you should cover the end grain with leather to restrict moisture exchange in the end grain. There are lots of ways to interpret this. One way would be: Leather can help keep a wet top from splitting.

In the next entry, I’ll discuss what I am going to do to answer these questions in my mind.

— Christopher Schwarz

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.

You could take a dried tendon, pound it to get strips, soften them in warm hide glue, then wrap them around the end of the board (leaving the grain exposed, but wrapping the other four surfaces). When the glue dries, the sinew will shrink slightly. This would in effect, band the wood as someone else suggested and keep it from splitting.

This technique is used to make composite bows which are made of horn, wood, and sinew. Horn compresses & returns to shape. Sinew stretches and returns to shape. A thin layer of wood is sandwiched between them to provide balance between the forces.

Regarding the leather or dried tendon end treatment – the notation that this material is superior to iron links suggests that the sinews are applied wet (or wetted with hide glue) and when dried will continue to apply sufficient compression to keep end grain checks from opening. It could also be intended to counteract cupping of the top, but application only at the ends hardly makes sense in achieving the goal. It might have been added as a moisture barrier (by intention), but one cannot ignore the mechanical effects that would also occur. This is inferred based upon the techniques of sinew backing bows. Jim Hamm, and the Traditional Bowyer’s Bibles , Bois D’arc Press, are good starting references for going down that rabbit hole.

All of that thinking does lead one down to the next step. Where are the examples of sinewed kitchen tables? Where are the old kitchen tables with curious rebates, dados, or mysterious stains along the ends? Where are the tales of Antoine fighting the dog that insists on chewing off the kitchen table end treatment? Is this a discussion of what could be done, rather than what was done?

I’m thinking along the same lines as Damien that the strap is about compressive and tensile forces – exerting tension to resist crossgrain expansion whilst allowing the contraction phase to occur naturally. A metal fixture would resist both and cause the wood jack itself apart in the centre if it shrank.

Clever stuff, I’ve plenty of experience splitting thick boards as they dry – perhaps this is the little nugget of historical genius I’ve been missing..!

Cheers,

Matthew

Hey Chris, this is a totally off topic question, but it’s been nagging me and this is the only way of contacting you.

Is there historical context or reference for flattening whetstones? As in the type of flattening we do nowadays, flatten every time we sharpen.

Thank you for your wonderful work, it’s been an inspiration.

Uncle Roubo, “AJ” to family members, told me that it was tradition for a father to secure green wood for a workbench when a son was born. This wood was then stored to dry until the child reached the age at which he could be apprenticed to a cabinet shop. By that time, the wood was sufficiently dry to fashion a first class workbench. AJ thought this was common knowledge and, as such, omitted it from his book. This approach is not unlike a father building up a dowry for his daughter. Clearly, being the father of a daughter, you yourself must have started building your daughter’s dowry when she was born. If not, how will you secure a good husband for her?

It seems to me that the leather straps had a 4 fold function.

1. To hide the end grain and beautify the table.

2. To permit limited wood movement that occurs

from season to season which is the normal

expansion and contraction.

3. To prevent the wood from splitting during the

process of moving.

4. To limit how much moisture the wood absorbed

through the various seasons.

As far as the work benches are concerned, it seems that

the same principle of limiting how much movement you

had from the wood which would necessitate the need

to flatten the top would apply.

Whether an individual used dried, seasoned wood for

the bench top or not would likely be dependent upon

the individuals experience and knowledge the individual

had prior to building the workbench.

A seasoned wood worker would likely have experienced

the annoying need to often flatten the top of his workbench

after having used green wood to build it and would in all

likelihood, use dried, seasoned wood on subsequent workbench

tops, to limit the amount of time wasted, flattening that needed

to be done to the top.

Likewise, an individual who was well read, would most likely

choose dried, seasoned wood to make a workbench top,

having read under the table section that dried, seasoned

wood was preferable for the top to limit wood movement

and how often the top needed to be flattened.

It is not inconceivable that the tip to use dried, seasoned

wood when making a workbench top would have circulated

not just through the community of wood working hobbyists,

but professionals, schools teaching the craft, and from Father

to Son as well.

The only times I can see where green wood would have been

used is in situations where there was not an ample supply of

dried, seasoned wood, or where the individual making the

workbench was an inexperienced woodworker and did not

have the benefit of a seasoned woodworkers expertise

and guidance.

When assessing what past generations practiced, always

keep in mind that they in all likelihood had more sense

than what modern day generations and historians like

to give them credit for.

There are modern day products like the Air Jordan pump

which allows the wearer to add air into the sole with a

pump, the design of which, was originally patented, if my

recollection is correct; in the 1800’s.

Take care.

So I am assuming that 1 thumb is going to be about 1 inch?

I guess that when Roubo says ‘nerfs de boeuf’ he talks about the neck ligament of an ox. They made walking sticks and composite crossbows with it. I imagine that the modern equivalent are thin metal straps with also a low compression resistance.

Pouce = inch not thumb in this case. I used to own a 16th c house in France and was puzzled by the dimensions of the windows till I figured out they were in inches, the older system. Even in modern France metric dimensions are not universal. Plasterboard is 2240×1120 or 8×4 feet!

“Straps attached above” seems to indicate across the top. Iron linking wouldn’t do anything to stop moisture exchange, so I don’t think he meant it in that way.

Hey Chris,

Minor translation nit: “rather than shrinking from the other side.” probably wants to be “rather than going hollow on the other side”; Creuser is very much “digging” or “hollowing”. I think Roubo prefers a crown to a hollow on the bench top.

I have a shiny new (about one year since the tree came down) slab of 6″ douglas fir that’s about to become a bench-top; I’ll report how it moves over the next few years. I’m not patient enough to let it season longer before I use it. But of course softwoods vs hardwoods…

Paul

It specifies dried ox tendon. The tendon across the end grain might act kind of like a vergy strong bungee and draw the wood of the table top together preventing splits. And,

since it would gain and lose moisture at the same rate as the wood it would allow some movement. I think……