We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

A few weeks ago I was invited by the Yale University Art Gallery to do a presentation on colonial wood turning. The event took place at their legendary Furniture Study in lieu of their weekly public tour. During the presentation, I highlighted the differences between the work of the cabinetmaker and the work of the turner and then discussed how lathe turning uniquely satisfied the demands of the preindustrial artisan and consumer. To bring this to life, I walked through Moxon’s text on turning while demonstrating the entire process. The guests got to see a billet split, hewed to round, and turned on a foot-powered lathe. I’ve written more about that presentation over at my blog, The Workbench Diary.

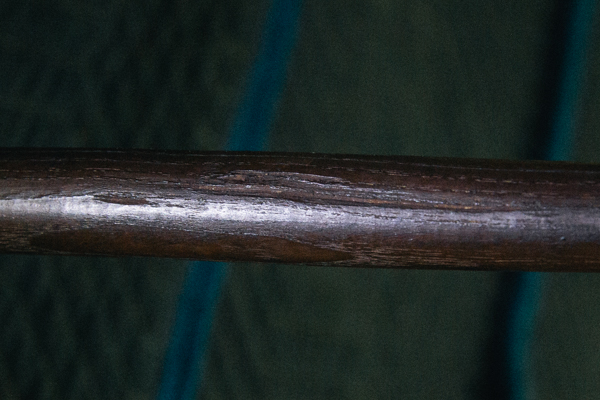

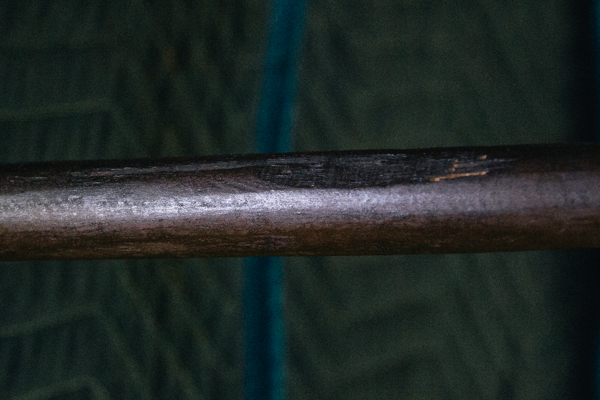

When I arrived to set up for the presentation, I had museum assistant Eric Litke, set out two chairs from their collection for comparison. I began my presentation by pointing out the differences and similarities. It wasn’t until later as I was at the lathe showing turning techniques that I commented about the tool marks and surface qualities of period turnings. I explained to them that the preindustrial pieces I see in my conservation studio almost always have areas of tear-out and/or riving marks. This “dawking,” as Moxon called it, was no reason for discarding the spoiled piece. The maker merely turned the flaw to the bottom or inside during assembly. This practice was par for the course, not an anomaly.

I told the audience that this was so consistent that I would be willing to bet that if we were to examine the turned chair I discussed earlier we would find exactly this kind of tear-out. That was the last thing we did together. As we walked out of the workshop, we made a semicircle around the chair while Eric laid it on its back. With flashlight in hand, we began investigating. I was relieved to find I had not overstated my case. Lightbulbs seemed to go off for folks as we enumerated the “dawks” and riving marks. On this particular example, it happens that every single component had at least one such major blemish. I also showed them the rippled surfaces of the “flat” parts of the turnings. The audience really seemed to appreciate these observations from a craftsman’s perspective.

So what should we learn from this? I don’t bring this up because I think we need to celebrate mistakes, but I do think we need to be realistic about our expectations. Frankly, foot-powered turning is not the same thing as relying on sandpaper at a motorized lathe. Even though I am aware it possible to turn a flawless spindle with foot power, I‘m telling you it’s not necessary. So if you’re one of those precision-oriented woodworkers, by all means, make chairs to glass-smooth perfection. But if you want to know how it was done historically, learn to hide your mistakes.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.

Joshua,

Thank you for the article! What a relief to hear that I stand in good company with my own “dawking”, and that my frugality in simply hiding the marks rather than throwing the component away and starting again is in fact a common practice going way back! (I thought I was just cheap – but it turns out I am just being “authentic”!)