We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

What is the best design for a round mallet? It has to do the job, feel good in your hand and remain comfortable as you use it. Three weeks ago, while at Peters Valley, I had a chance to make a few mallets and try out their feel and comfort levels.

What is the best design for a round mallet? It has to do the job, feel good in your hand and remain comfortable as you use it. Three weeks ago, while at Peters Valley, I had a chance to make a few mallets and try out their feel and comfort levels.

Round mallets are easily turned on the lathe (although the 4th graders in my school carve them out from branches) and because the machine room had an amazing collection of lathes, I couldn’t resist the temptation to re-hone my turning skills and make a mallet or two. I am not an expert turner but I know my way around the lathe and can produce a decent bowl, a furniture leg or a cutting-board handle. I know I rely too much on sandpaper, and occasionally my spindle gouge catches on my revolving blank, but I am able to turn well enough to execute my designs.

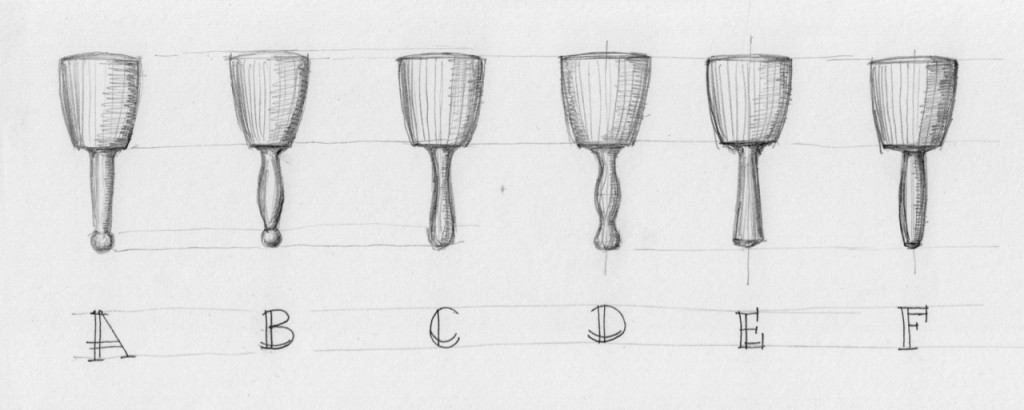

It seems that there is consensus amongst woodworkers on best shape for a mallet’s head. In most cases it looks like a bulging frustum (it’s geometry, trust me; it means a barrel-shaped cone). Therefore, I decided to concentrate only on the handle design.

Below are my illustrations of common mallet shapes.

I turned my first experimental mallet as part of my spindle turning demo. I decided to turn a mallet that would be long and hefty, to be used mainly for driving a froe into logs for splitting them. As a turning blank I used a seasoned beech branch that I brought from home. My design followed (more or less) options B and D in my drawings.

When turning an object such as a tool handle, it is good practice to turn it oversized, then remove the object from the lathe, hold it in your hand and try to simulate its use. Or even better, to do some actual work with it. Then bring it back to the lathe and slim it down as needed. This process took me a while but it was worth the effort because in the end, the mallet turned out comfortable to hold and effective in use.

After finishing my demo and while my students were venturing into this craft, I decided to keep my experiment going and make a few prototypes to help me figure out the best design for my hand. I grabbed a short ash log I’d brought from home. I’d kept it outside our garage for a year and planned on splitting it into four parts. First I tried to cleave it by driving a carpenter’s axe into it (I left my froe at home) but even under many persuasive blows from my awesome new mallet, the log didn’t budge. Perhaps it was just too dry, or my carpenter’s axe blade was too thin for cleaving? So I decided to use a band saw instead. After sawing the log into four parts I began turning the mallets.

No matter how hard I tried, I could not cleave this log. It might have been because it was just too dry, or perhaps because I should have used a splitting axe instead.

Please stay tuned; next time I will show each of my mallets and grade them according to my own comfort scale.

Editor’s note: Want to get started in turning? Check out our online show “Woodturning with Tim Yoder,” with new episodes every two weeks (each is available for free viewing for eight weeks after it’s posted. You can also find collections of the episodes at ShopWoodworking.com. Now available are Season 1, episodes 1-6; Season 1, episodes 7-12; Season 1, episodes 13-18; Season 1, episodes 19-24; and Season 2, episodes 1-6.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.

Would boisdarc/Osage orange be a good wood to use for a mallet? It’s a very hard yellow wood. I have quite a bit of it that had been dried for about 5 years.

About 30 years ago I made a heavy 4 legged carving stand out of 2 x 6 with a bowling ball as the pivot thru which I had drilled a hole and inserted a threaded carver’s screw. I was quite proud of the out come, so I stained it and finished it like fine furniture. Well I figured that fine stand deserved to be used with a fine wooden mallet. I turned the head using a piece of hard maple and then turned a handle of walnut. Likewise that too was a beautiful project, but that mallet was too beautiful to EVER use! To this day it hangs beneath that stand as a reminder that useful hand made tools need not be beautiful.

A naive question, why is ash a bad wood fora Maul/mallet head?

The heaviest mallets (for stone) carving are made of lignum vitae of course, but in college I just couldn’t afford one so I made a slightly larger mallet from osage orange. I carved it green but it never cracked in the slightest. I made the handle like a competition shooter’s handle, with a groove that fit each finger as I didn’t want to kill a fellow student if it slipped away from me. It was a little heavy for woodwork but I loved that mallet. Sadly, I lost it to an arsonist in ’06.

The reason you can’t split your log is due to the branches that were growing out of it. You can still see their patterns in the lobes under the bark. The fibers around the branches do not grow straight up and down, which makes it very difficult to cleave it and to turn it. I’ve turned several carving mallets, out of a few different species. I think you would find that hard maple takes the abuse of a froe better than the ash you chose, with much less splitting. Also, if your log is green, it will dry with more deformities than a straight grained section.

So far, I made my two favorite mallets from dogwood and hophornbeam. They are almost indestructible.

If you turn the center of the end of the mallet slightly concave, it will be easier to find and less likely to roll off your bench and onto your foot. Turn the outside edge of the end rounded and convex, so it will be less likely to start a split. Think of the bottom of a coffee cup.

I’m continually inspired by your skills with a pencil as well as your woodworking Yoav. I’ve never used a round mallet before, it would be interesting to give one a try.

Cheers

Graham