We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

Research gives names to unknown artisans.

David Rowley, Freegift Wells, Amos Stewart, Orren Haskens, Eli Kidder…ever hear of these guys?

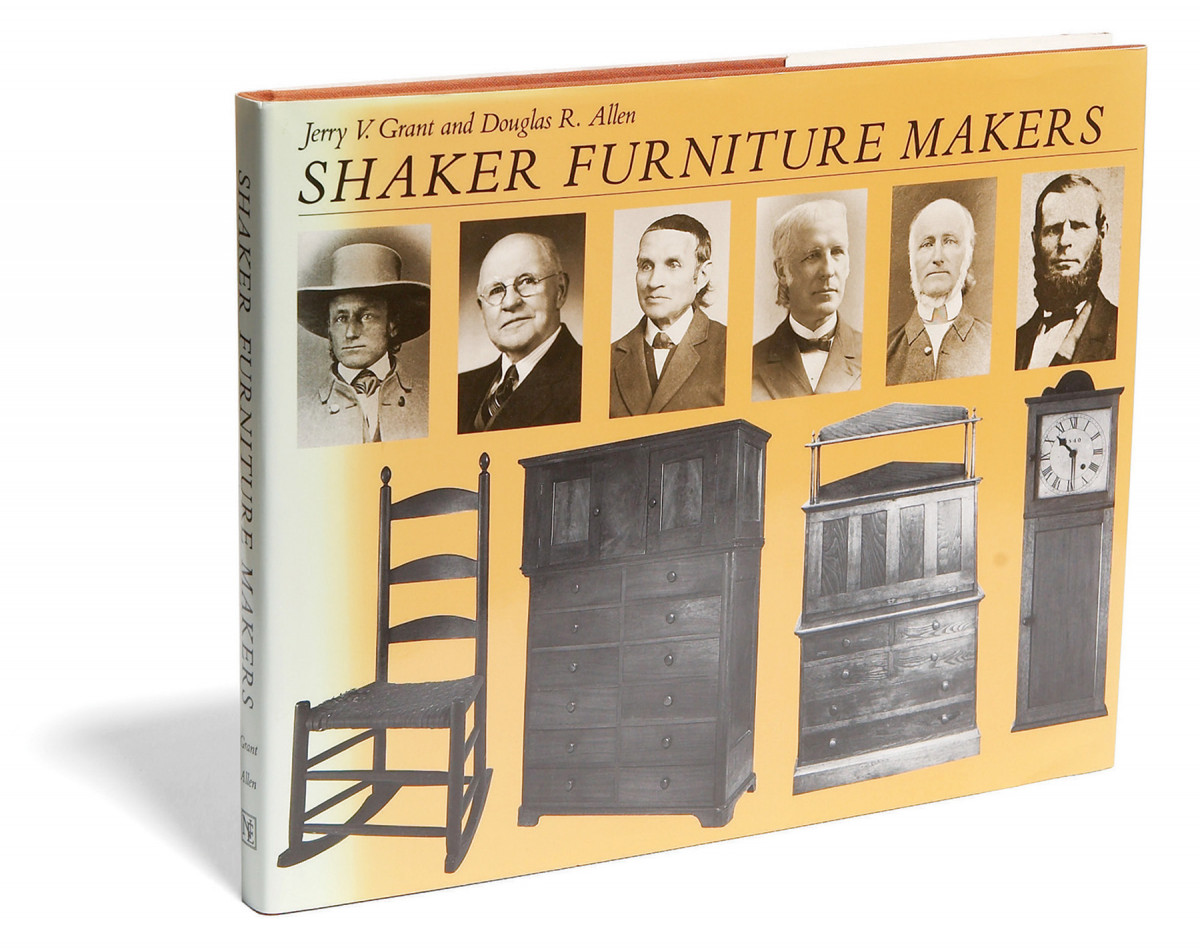

They were Shaker cabinetmakers, the names behind one of the most unified and influential movements in American furnituremaking. You might think that they would have been completely anonymous, like most woodworkers of that era, but a remarkable project by Shaker scholar Jerry Grant, undertaken in the 1970s and 80s, has brought to life these and other artisans–27 utterly fascinating people–in Shaker Furniture Makers (1989).

Grant drew heavily on journals kept by the Shakers, discovering detailed descriptions of their joinery and finishing techniques. You won’t find much of that technical information in this book, but you will find a well-written set of stories about a set of celibate artisans who labored under different aesthetic and philosophical constraints from those of today. Grant writes:

Even though the Shaker craftsmen worked for the good of the community more than for personal advancement, they were in many cases strong individuals. Many were saintly in their devotion; some had strong fleshly appetites for things of this world… Some of their intense personal efforts [to remain true to Shaker ideals]…were in vain. Some of the master craftsmen left the Society, while others remained Shakers for life.

Even though the Shaker craftsmen worked for the good of the community more than for personal advancement, they were in many cases strong individuals. Many were saintly in their devotion; some had strong fleshly appetites for things of this world… Some of their intense personal efforts [to remain true to Shaker ideals]…were in vain. Some of the master craftsmen left the Society, while others remained Shakers for life.

Shaker style evolved over the years, but at its high point in the first half of the nineteenth century, it was a pure form of a rectilinear Federal style popular in the world outside the utopian Shaker villages. Remove the inlay, simplify the molding, use only local woods–and you have the basis for many Shaker pieces. Of course, all this was done in the name of a higher cause. Grant relates one telling example: “In the summer of 1840, David Rowley removed the superfluous brass pulls on drawers and replaced them with wooden ones, which were deemed, through spiritual communication, to be more appropriate to Shaker life.” Imagine building to please those clients!

Many Shaker pieces were unsigned, so how do you tell who made what? Well, how they were made. One way is to look at how. Grant writes about an unusual method of dovetailing drawers that can be traced to the work of Abner Allen and Grove Wright, of the Hancock Bishopric. On more than thirty pieces, these artisans tapered the sides of their drawers, making the sides narrow at the top and wide at the bottom. This meant that the wear surface on the drawer’s bottom was wider than normal–and thus would presumably last longer–while the top of the side would have a more delicate look. Cutting dovetails for tapered sides is definitely more difficult than straight sides.

A few years ago, I found a chest at a flea market whose drawers were made this way (right). The drawer sides are pine, and although their bottom edges are 3/4” wide, they’re quite worn down. The chest was covered in black paint, and cost very little. Underneath the paint were beautiful birch boards, flaunting large, tight knots and sensuous crotch grain. The lines of the chest were very plain–but not like any Shaker piece I’d seen. Clearly, the maker had fallen in love with some unusual wood.

Who made this piece? Did Allen or Wright train this fellow? Could it have been a young man who left the sect because his “fleshly appetites” were too strong? Reading Shaker Furniture Makers makes me wish that we all left more behind than just our work, because someday, somewhere, someone might ask, “Who was that guy?”

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.