We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

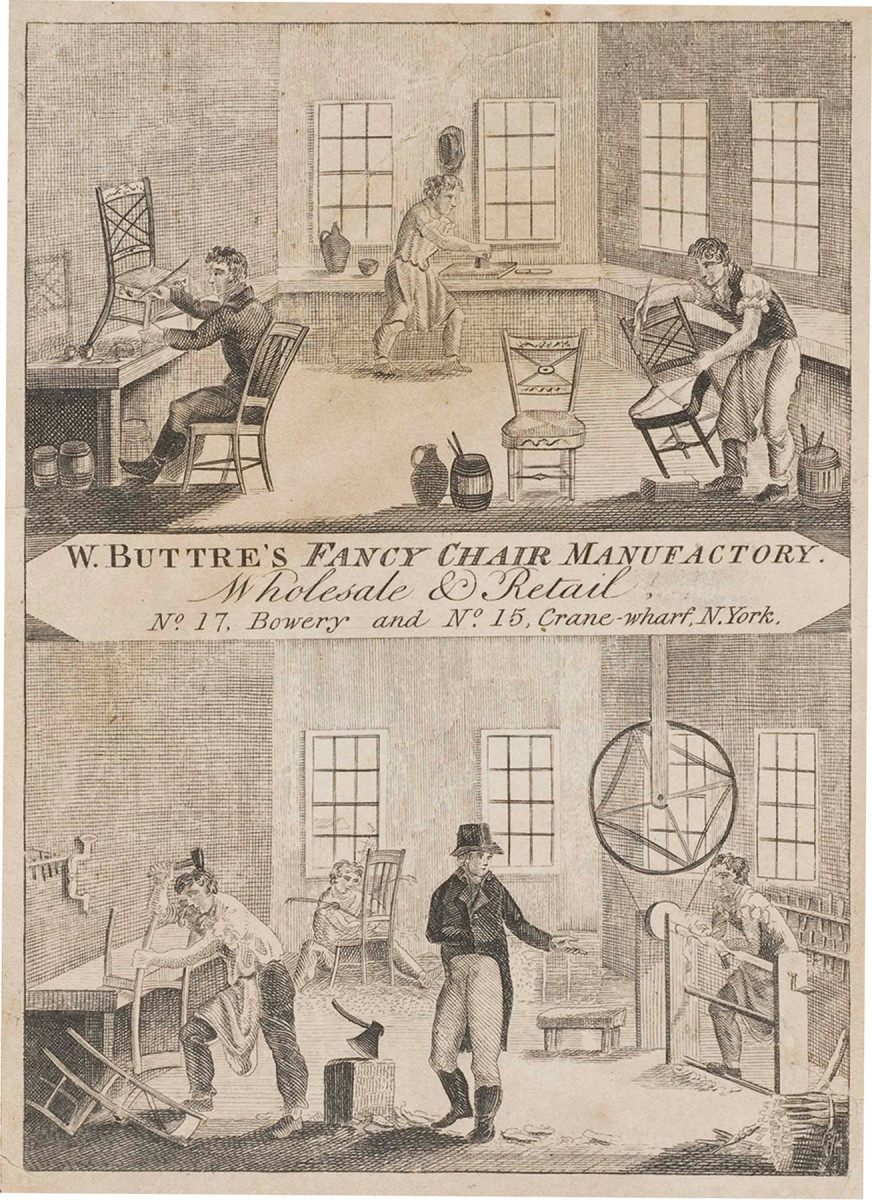

Trade label. This W. Buttre trade card, circa 1813, shows chairmaking apprentices at work. Courtesy, The Winterthur Library: Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera.

A brief history of a not-so-romantic woodworking education system.

Ever since the renewal of interest in woodworking in the 1970s, especially among amateurs and small-shop professionals, there has been talk of reestablishing an apprenticeship program similar to what existed hundreds of years ago. But what was that apprenticeship system like?

To describe it I’m going to go a little off my usual topic of finishing, because shops before the American Revolution were small, and finishing was too simple and too small a part of the job to have spawned a specialized “finisher” craft. Those who did the finishing were the woodworkers themselves ,who were usually divided into specialized categories: cabinetmakers, chairmakers, joiners, clockmakers, turners, etc.

And these woodworkers were a part of the larger artisan/mechanic category (artisans were often referred to as “mechanics” at the time), which included all skilled craftsmen, from tailors and shoemakers to silversmiths. So any discussion of finisher apprenticeship is really a discussion of craft apprenticeship in general.

The English Guilds

Beginning in the Middle Ages in Europe, each craft organized itself into its own guild composed of masters and journeymen to protect the interests of the members. By controlling the number of apprentices admitted and the education standards – for example, the requirement to produce a “masterpiece” at the end of the training – guilds were closed labor markets that were able to keep wages and standards high.

Apprenticeships served a much larger purpose, however, than just job training where the special skills (“art”) and special knowledge (“mystery”) were passed down from one generation to the next.

Boys (they were almost always boys) were just 12 to 14 years old when they were apprenticed to a master craftsman. So an apprenticeship was also meant to instill a proper moral development overseen by the socially approved master and was a means of control over potential socially disruptive teenagers.

Not every boy became an apprentice, of course. Farmers’ sons usually became farmers. Sons of the wealthy leisure class were usually educated to join that class. Many boys grew up to join the growing merchant class. And many boys from poor families grew up to do manual labor, join the military, become servants, or even become beggars.

There was a hierarchy among the crafts, determined partly by the craft’s earning power and partly by what it cost to set up as a master. For example, having completed an apprenticeship as a tailor, all a person needed to start a business was needle and thread, and a tape measure.

In contrast, a cabinetmaker required a large array of tools, so it was rare that a graduating apprentice could afford to set up a shop. Almost always, he had to work many years as a journeyman to save up the funds.

The term “journeyman” derives from the need of the graduated apprentice to journey to wherever he could get the best wages.

Colonial America

Colonial America was made up of English colonies, of course, so the laws and traditions of England applied here as well. But though the apprenticeship path to learning a craft and developing proper moral standards flourished, especially in the Northern colonies, guilds never took hold.

The reasons were a shortage of skilled labor, free land to the west, vast distances, and a poorly developed legal system. Whereas in England it was rare for an apprentice to run away from a master before he had learned the craft (he would never find employment elsewhere), it was not uncommon in America.

You may recall the story of Benjamin Franklin running away to Philadelphia from his printer apprenticeship in Boston long before he had completed his training. Once in Philadelphia, he represented himself as a journeyman printer and had no trouble finding work.

In America, you were then (and you still are today) who you say you are – so long as you can pull it off.

The price that was paid for this freedom was a lower quality of craftsmanship overall than existed in England. We have numerous examples of very high-quality furniture pieces that have survived from the Colonial period, so you may not have thought of the colonists’ skills as below par. But the skills of many were, and their furniture hasn’t survived.

While you’re contemplating this, keep in mind that many of the craftsmen working in America had been trained in England or elsewhere. It’s still that way. For example, in a craft I know a lot about, a highly disproportionate share of the most skilled furniture restorers in the U.S. today were trained somewhere else.

Also, the crafts were more highly developed in the Northern colonies than in the South. In Southern colonies, a good deal of the labor, skilled or not, was performed by indentured servants or slaves. The apprenticeship system wasn’t nearly as well developed.

The Life of an Apprentice

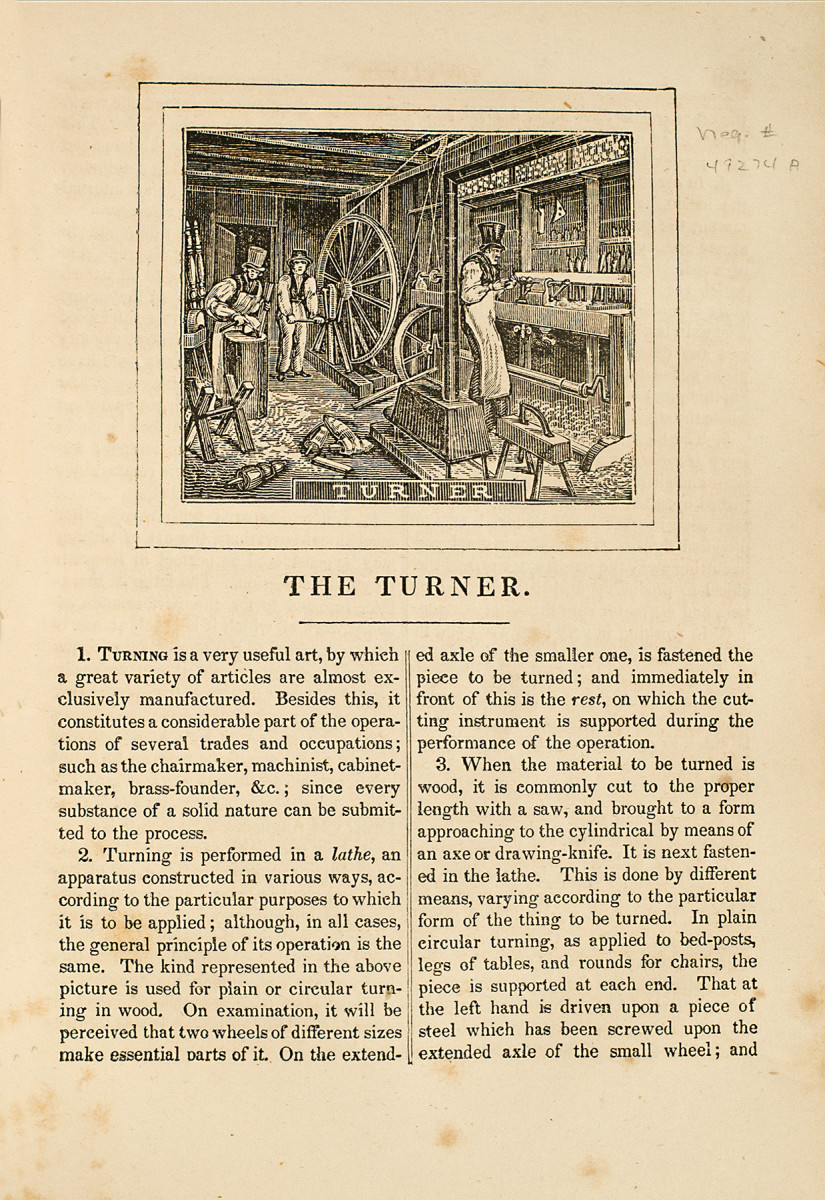

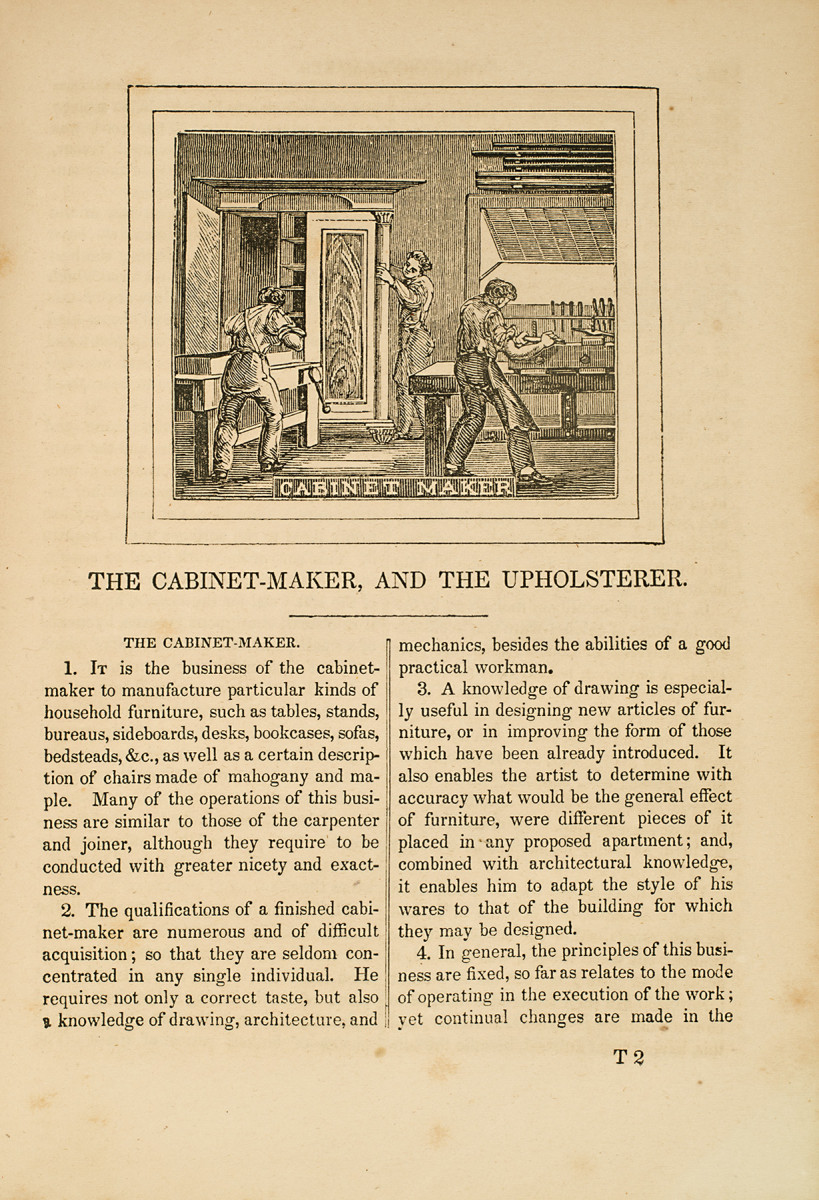

Building trades. These illustrations show apprentices at work in a turning shop and cabinetmaker’s shop. From “The Panorama of Professions and Trades; or Every Man’s Book” by Edward Hazen (1837). The book – available free online – is a fascinating romanticized read on educating children for future professions.

Apprenticeship in America could be very hard, partly because the master himself might be poor and partly because masters often took advantage of apprentices, making them do menial chores for years without teaching them anything about the craft.

Apprenticeship in America could be very hard, partly because the master himself might be poor and partly because masters often took advantage of apprentices, making them do menial chores for years without teaching them anything about the craft.

In the colonies, there was always the possibility that the apprentice might run away, so masters often held back training until the later years to try to keep this from happening.

Moreover, apprentices were often poorly fed and beaten. Remember that they were only children.

Apprenticeship usually began with a short trial period, from weeks to half a year, for the master and the father of the boy to decide if they wanted to continue the relationship. Then a contract was signed by the master and the father, which usually specified that the master would feed, clothe and house the boy and teach him the craft. The master might also be required to provide a general education.

In England the father would usually have to pay a fee to the master. In America this was most often the case only with the higher-status crafts.

At the end of the contract period, which could be for as long as seven years, the master would provide the “graduated” apprentice with a suit of clothes and send him on his way.

Sometimes, the master would agree to pay journeyman’s wages to the apprentice in his final years.

But the opposite was also common. It was cheaper to keep an apprentice than to hire a journeyman, so masters often had apprentices doing journeyman’s tasks for as long as they could get away with it. Their success with this usually had something to do with the state of the economy at the time: Did the apprentice have other opportunities?

Apprenticeship Today

When we think of apprenticeship in the 20th and 21st centuries, we don’t mean for it to be as all-encompassing as it was in the 17th and 18th centuries. We usually mean for it to be a trade off: working for free, or at least for very little pay, for a fairly short time, in return for instruction in the craft.

This is very different from what apprenticeship used to mean.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.