We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

An illuminating look at the life of a 19th century country cabinetmaker.

Daydreaming in my shop, I’m imagining a warm summer day way back in 1899. Just after supper, Henry Lapp sits at a pine table outside a tavern on the Lancaster Turnpike, a few dusty miles past the long bridge over the Schuykill River. He’s a cabinetmaker from the heart of old Amish country in Lancaster County, some forty miles away—from a town called Bird-in-Hand, to be exact—and he’s on his way to Market Street, in Philadelphia, to drum up some business.

Henry has a new idea for a washbench, an important piece of furniture back home in the country. It typically holds water buckets for scrubbing freshly-pulled vegetables or dirty hands. Most washbenches were humble affairs, but this one is stylish: It will have a two-level, tin-lined recessed top, graduated drawers and compound bun feet. It’s an ambitious piece.

Henry is busy sketching his washbench in a small store-bought notebook which has a plain, soft cover and a sewn binding. As the sun goes down, he slips the notebook into his coat pocket. Eventually, this book will contain over 50 pages of projects that Henry has built or would like to build— everything from a drop-leaf table to a set of ingenious mousetraps. It’s his catalog.

This sketchbook is Henry’s only way of communicating with his customers. Henry Lapp was born deaf and is partially mute. He’s learned his trade just by observing other men at work.

Fast forward fifty years. Henry’s sketchbook has lain, untouched, in the top drawer of a small bureau—one that Henry may well have made himself, although we’ll never know, for he didn’t sign his work. The bureau is a quaint antique that’s just been sold by one of Henry’s descendants. The dealer who bought it is removing the odds and ends typically left in an old chest when he discovers this slim volume, one of the most valuable documents illuminating the life of a typical country cabinetmaker in the 19th century.

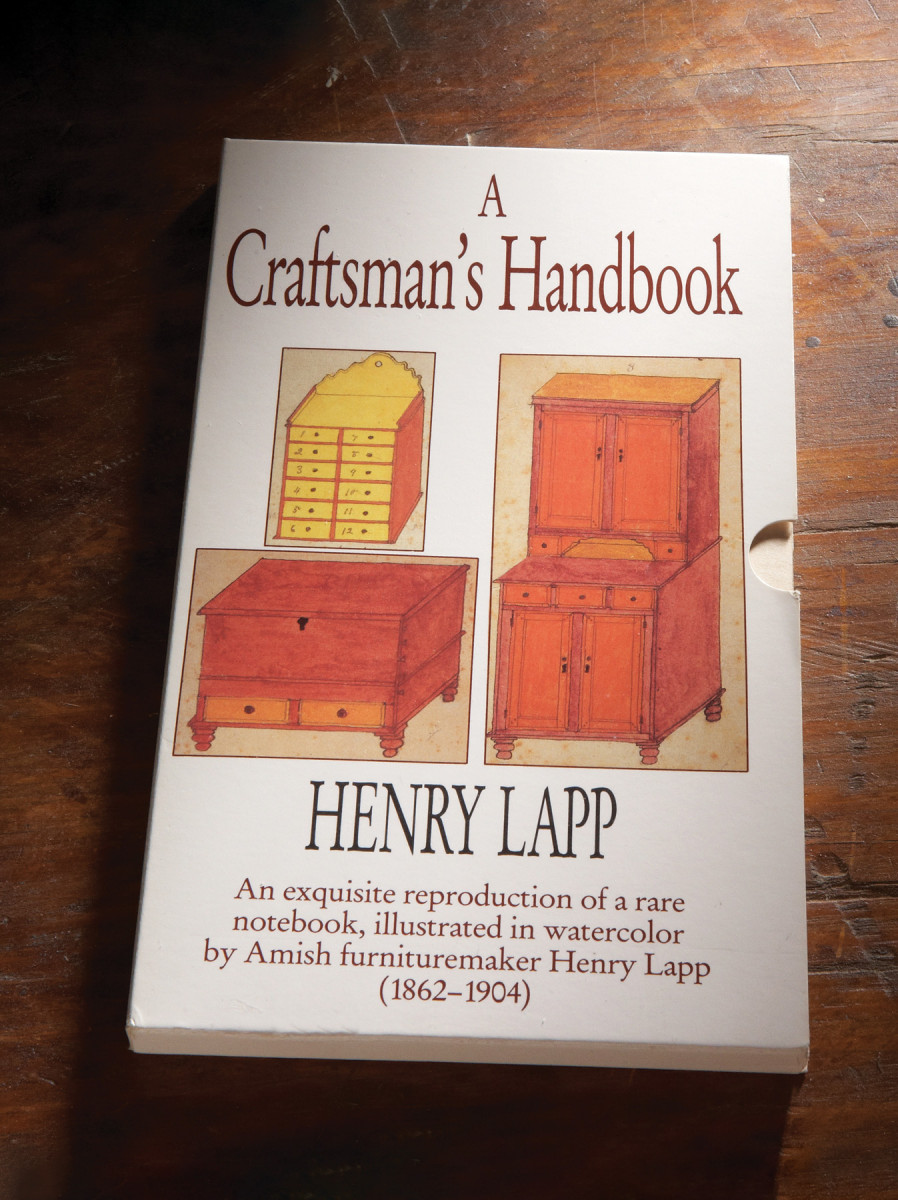

Today, Henry Lapp’s book sits in the archives of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Back in 1975, at the height of America’s interest in folk art, the museum published a facsimile edition of this book. It’s still available through used bookstores on the web at a very low price. Each page is accompanied by a fascinating commentary by Beatrice Garvan, a curator at the museum.

Henry’s sketchbook is a beautiful object in its own right. A skilled artist, Henry painted all of his pencil drawings with yellow, red and green watercolors. Like the Welsh immigrants who lived just to the east of Lancaster County, Henry used washes with vivid colors to brighten up inexpensive poplar and pine furniture.

The pages of Henry’s sketchbook are so evocative that the Philadelphia Museum has reproduced many of them as posters and art prints. One of the finest prints is bursting with ideas, with drawings of an eggbeater, a salad sower, a cutlery box, two pie crimpers and three bent-wire bread toasters, cheek by jowl.

These everyday objects, along with seed drawers, trellises and those mousetraps, fill the back pages of Henry’s inventory of designs. The front pages—no doubt the ones he would show first to those customers on Market Street—display Henry’s finest pieces: his furniture. The breadth of his work is amazing to a modern woodworker, but would probably be no surprise to any of Henry Lapp’s neighbors. In a way, Henry was ultramodern. He served his community making simple, functional objects using a local resource—the trees of Lancaster County.

For more information on Henry Lapp, see “A Craftsman’s Handbook: Henry Lapp,” published by Good Books in 1975, and “Two Amish Folk Artists: The Story of Henry Lapp and Barbara Ebersol,” by Louise Stoltzfus, also published by Good Books in 1995.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.