We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

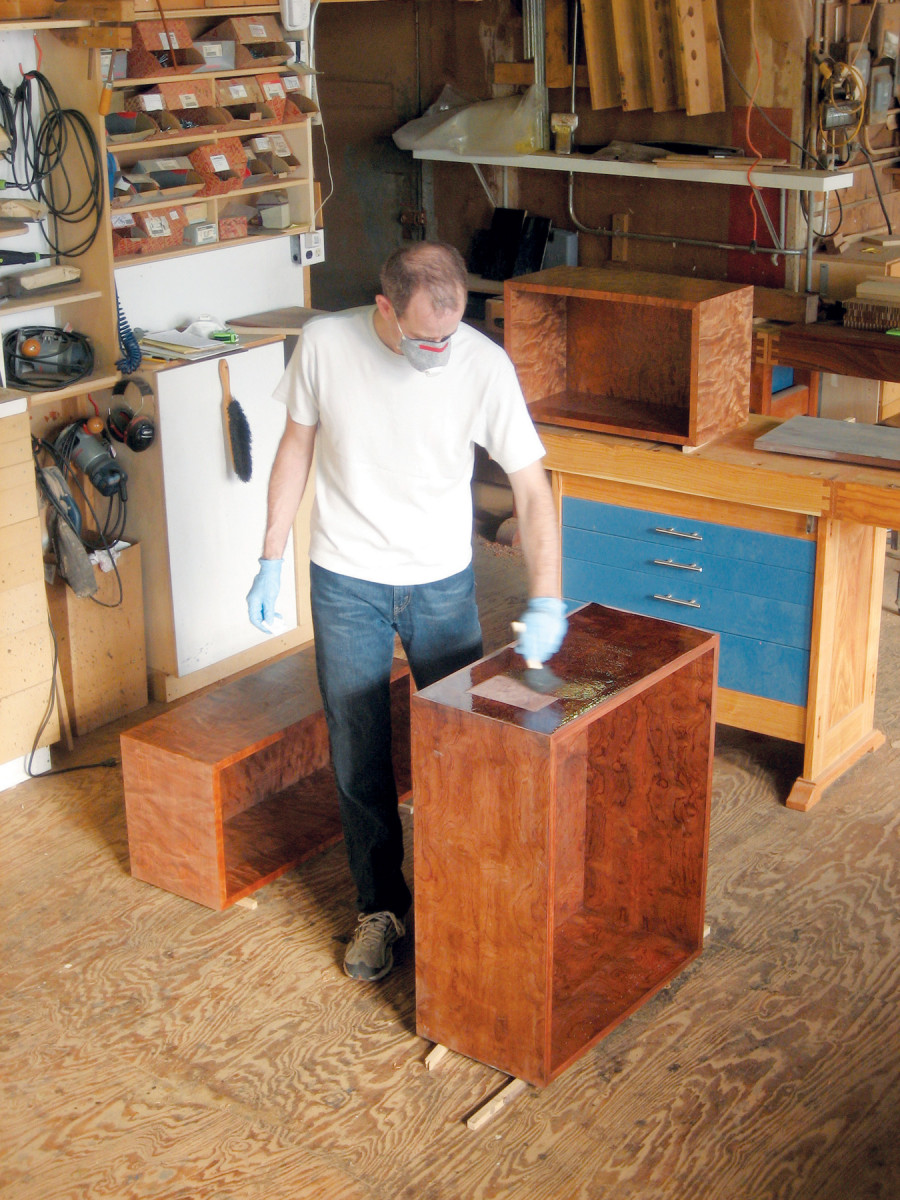

Photo 1. Brushing a finish is much easier if you can apply a thinned coat on horizontal surfaces before assembly. All glue joints, like these mortise and tenons, should be masked off.

A Disposable Brush And A Few Rags Build An Awesome Finish.

Finishing is a challenging aspect of woodworking. There are many finishing materials and methods of application; within a single piece there may be several conditions requiring different approaches. It is one thing to get a nice finish on a small flat sample board but what about inside corners, vertical surfaces, curved areas, thin edges and framed panels? It may be tempting to think of spraying as a cure-all but spraying comes with its own set of problems and still requires a lot of effort to get a luxurious surface.

This article presents a technique to help you apply a finish by hand, using only a brush and some rags. The sequence calls for a thin coat or two of polyurethane, scuff sanding and final coats of a wiping gel varnish to remove the sanding haze.

The goal is a finish that appears level and clear, shows the pores and texture of the wood, and feels very smooth (even on inside corners). I like a slightly glossy sheen. If it has been applied and handled properly, it will appear as an integral part of the surface and not like a plastic film.

Hand applying a finish has many qualities in common with hand tool work. The process is quiet, meditative and benefits from a eye for detail. It also requires practice to perfect.

Materials:

- Brushes: 3” foam brushes with wood handles. Cut about 1” off the end of the handle, sand the edge and so the brush can be stored in the quart can of finish. This eliminates the use of solvents to clean the brush.

- Polyurethane: I use semi-gloss Minwax Fast Drying Polyurethane for the interiors of cabinets and gloss for the surfaces on the outside.

- Thinner: Naptha is better than paint thinner as it evaporates faster. The goal is to thin the poly so that it will flow out better without extending the drying period too much.

- Gel Varnish: Bartleys Gel varnish handles well and only comes in satin.

- Sandpaper: You will need stearated sandpaper in 400, 600 and 800 grit.

- A felt block for backing your paper.

- Cotton or paper wipes. I use Taskmate/Brawny Industial.

- Japan drier, available at most paint stores.

Apply The Polyurethane Varnish

Start by sanding everything to 180-grit then wet the sanded surfaces with water. After it dries, scuff sand the raised grain with a felt block and 220-grit paper. Dust or vacuum the dust. The surface doesn’t have to be spotless because the scuff sanding between coats will smooth out any vagrant dust in the finish. I don’t bother with a tack rag.

I completely pre-finish all the interior surfaces and partially finish the exterior surfaces of a cabinet before assembly. Pre-finishing lets me work on flat, horizontal surfaces without having to brush into an inside corner (Photo 1). Mortises, tenons and all glue surfaces should be taped off. I use basic masking tape and a utility knife to trim the tape after it is applied. I finish one surface at a time, letting it dry completely before turning it over to finish the opposite side.

The first coat is polyurethane that’s been thinned until it is more like water than syrup (usually about 20% naptha by volume). The exact amount is not that important. What you want is a coat that flows out and stays wet while you brush. Add 1/3 of a capful of Japan drier to help speed the curing.

A natural bristle varnish brush requires lots of solvents to maintain. I simply use a disposable foam brush and store it in the partial can of varnish I’m using. One brush will last for all the coats I apply.

Photo 2. Brush a perimeter of finish on the surface of a panel leaving a dry edge to prevent drips. Sticks elevate the panel and facilitate working the edges.

Working with foam brushes requires some getting used to. Dip the brush halfway into the finish, let it drip back into the can a bit and quickly move the brush to the work piece without dripping. With practice you will get a sense for the right amount of finish to load into the brush.

Photo 3. Fill in the perimeter. Lay out an even, wet coat of polyurethane over all but the very edge. No need to worry about brush stroke direction yet.

Foam brushes tend to push a small puddle of finish in front of them. To avoid pushing the finish over an edge, I start by applying a perimeter of finish roughly 1-in. from the panel edge, (Photo 2). Then, work the finish back and forth to fill in the middle (Photo 3). Be sure to keep shy of the edges.

Photo 4. Brush the dry border. Hold the brush lightly, barely overhanging the edge. Make the brush stroke parallel to the edge.

Next, brush the dry border with a brush that’s just loaded enough to wet the wood but not enough to leave drips on the edge (Photo 4). Go back over the entire surface, in any direction, to move the finish around and create a thin even film with no puddles or dry patches.

Photo 5. The final strokes are made with the grain. Hold the unloaded brush lightly with just the tip touching and come in to the surface on a long low angle like a plane landing. Use a raking light source to check for puddles or dry spots.

“Graining” is the term I use to describe the final brush strokes made parallel to the grain (Photo 5). Start the strokes just in from the edge and continue all the way off or past the opposite end. The only downward pressure should be from the weight of the brush; you are just lightly smoothing the finish in the direction of the grain and don’t want to push finish over the edge.

The raking light should reveal a thin, even and level coat of finish with the brush marks starting to flow out and disappear. If you see puddles or dry spots you can move the finish around with the brush and then re-grain with light strokes.

Photo 6. Finish the edges of interior parts by brushing on the finish then wiping it off immediately. Use a tightly folded wipe or rag to avoid disturbing the top finish. Be sure to clean the underside of the edge as well.

At this point I tackle the edges of the inside parts. I brush poly on these edges and wipe it off right away with a cloth (Photo 6). This leaves a thin film of varnish that won’t sag or drip. The thin film offers enough protection for edges that are inside a cabinet (like a shelf). Use your raking light to check for a ridge of finish that may have been pushed onto the top. Re-grain with a light brush stroke on the top if necessary.

For exterior edges I support the dried panel vertically so that I can brush on the now horizontal edge. Use the tightly folded towel to wipe any drips off the pre-finished top and bottom surfaces.

Photo 7. Curved surfaces will test your skills. Use a less saturated brush with a light touch and check repeatedly for drips or sags. It’s important to catch them early so they can be brushed out before the finish gets sticky.

Curved parts are brushed with a drier brush (Photo 7). Dip the brush tip in the finish and brush lightly with the brush held in a more vertical position. Limit your brushing area to one face and brush out a thin even coat. Wipe off the adjacent faces to remove any drips.

Photo 8. Scuff sand with 400-grit paper on a felt block after the first coat has dried overnight. The goal is not to remove material, just knock off the raised fuzz and make the surface feel smooth.

When you are done, clean the rim of the can, drop the brush in it, hold a deep breath for a minute and exhale into the can right before placing the lid on. This will replace the O2 in the can with CO2; and minimize skinning.

Photo 9. Apply the gel varnish to all the interior parts with a foam brush. The gel varnish covers up the scratch pattern made by the sandpaper.

The next day, scuff sand the seal coat (Photo 8). A light but comprehensive sanding is all that’s required. Sand very lightly near the edges where the finish can be extra thin. The wiped off edges should already be smooth. If you find you need to sand out a little fuzz on the edges, use a light touch some folded up 800-grit paper. At this point, I apply 2-3 coats of gel varnish to the interior surfaces only (Photo 9).

Photo 10. Wipe off all the gel with two rags and two hands. Get two fresh wipes and firmly re-wipe the piece with the grain. Pay particular attention to the beginning and end of the wiping stroke. Push down hard as you leave the board to remove the sticky remnants that remain near the edge.

Brush the gel on most of the part and then smear it over the entire surface and edges with a wipe in each hand. Switch to a new set of wipes to remove all the excess gel varnish (Photo 10). Any remaining gel will dry to a sticky mess, so get it off now. Use a clean folded wipe off the edges. Remove any vagrant gel from the underside of the part and clean off smudges from your hand on the top.

Photo 11. Apply a second coat of poly to the outside of the cabinets after the interiors are done and the cabinets are assembled.

With the interior surfaces finished I assemble the case and apply a second coat of poly on the outside of the cabinet (Photo 11). I only do one side at a time, rotating the case to bring a new side horizontal after the previous side has dried.

Photo 12. Wipe up any drips that form on the cabinet edges with a folded towel.

Usually I can do 2-3 sides of a case a day. Blankets and padding are important to protect the sides from damage as you rotate the cabinet. Wipe off any drips that may form on the edges (Photo 12).

Photo 13. Lightly sand the exterior surfaces with 600-grit paper. Be very circumspect near the edges. Sand to within 1/8-in. of the edge and then do light passes on this sand-free zone, barely letting the block go over the edge.

Wait at least 2 days for the second coat to dry. Then scuff sand lightly with the 600-grit to dull out about 30% of the glossy surface (Photo 13).

Photo 14. Final sanding is done on the exterior surfaces with 800-grit paper and should leave a level surface. Look for a 90% sanded surface with an even pattern of small shiny pores when you wipe off the dust.

Repeat with 800-grit paper and the felt block. This time, push down harder to level the surface (Photo 14).

The next step is to use a gel varnish to cover the scratch pattern from the sandpaper just as you did with the interior surfaces.

Note: The used wipes should be individually spread out to dry when you are done.

Subsequent coats of gel will reduce the sanding haze. Usually I will apply 2 to 5 coats of gel on top of the poly to get the finish I am looking for. For my really special pieces and on dark finishes I will polish with 3M’s Imperial Hand Glaze #5990 between the last coats of gel. I rarely use wax except on thin or satin finishes.

This finish sequence can be used over dyes and stains but you must be very careful near the edges, especially with dyes. Dark colors will require more coats of gel and Hand Glaze polishing to remove the haze.

Photo 15. Keep applying gel coats on the outside of the case until you get the look you’re after.

Over the years I have found this approach reduces the finishing process to manageable steps. When each step is performed well it consistently yields a great, trouble-free finish (Photo 15).

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.