We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

Finish test. Oils and oil/varnish blends dry soft and wrinkled. Wiping varnish dries hard and smooth. So the easy test is to put a puddle on a non-porous surface such as the top of the can and see how the puddle dries. Both of these products claim to be oil, but Daly’s Profin is clearly varnish.

How can something so simple be made so hard to understand?

It’s probably fair to say that a majority, or at least a large minority, of woodworkers use a finish they can wipe on and off the wood. No expensive spray gun; not even any brush cleanup. Simple.

At least the application is simple. But these finishes have been made the most complex and confusing of all finishes by manufacturers striving for an edge (they want to convince you they have something special) and writers who either buy into the marketing or simply don’t know what they are talking about.

Wipe-on Finish Basics

There are four primary types of wipe-on finishes:

• Oil (boiled linseed and tung)

• Wiping varnish (alkyd or polyurethane varnish thinned about half with mineral spirits)

• Blends of oil and varnish (thinned or not)

• Gel varnish (alkyd or polyurethane varnish in a “gel” consistency).

Each of these finishes can be wiped or brushed, or even sprayed, on the wood and then wiped off.

Oils and blends of oil and varnish don’t harden well, so all of the excess has to be wiped off or the surface will remain sticky.

Wiping varnish can be wiped off, or it can be left damp or wet on the wood to build faster because it dries hard.

Gel varnish also dries hard but you can’t leave a thick layer without getting streaks or brush marks, so it’s better to wipe off the excess.

All of these finishes can be combined (and also thinned with mineral spirits) in any proportion, with these caveats: Adding oil to varnish means the finish can’t dry hard, so all the excess has to be wiped off, and adding any of the liquid finishes (or thinner) to gel varnish reduces the gel quality of the product.

I think this is pretty simple. But all kinds of problems are introduced by inaccurate labeling, marketing and descriptions. I’m going to discuss three: Labeling a thinned varnish “tung oil,” claiming that the product polymerizes and calling varnish “resin.”

Tung Oil

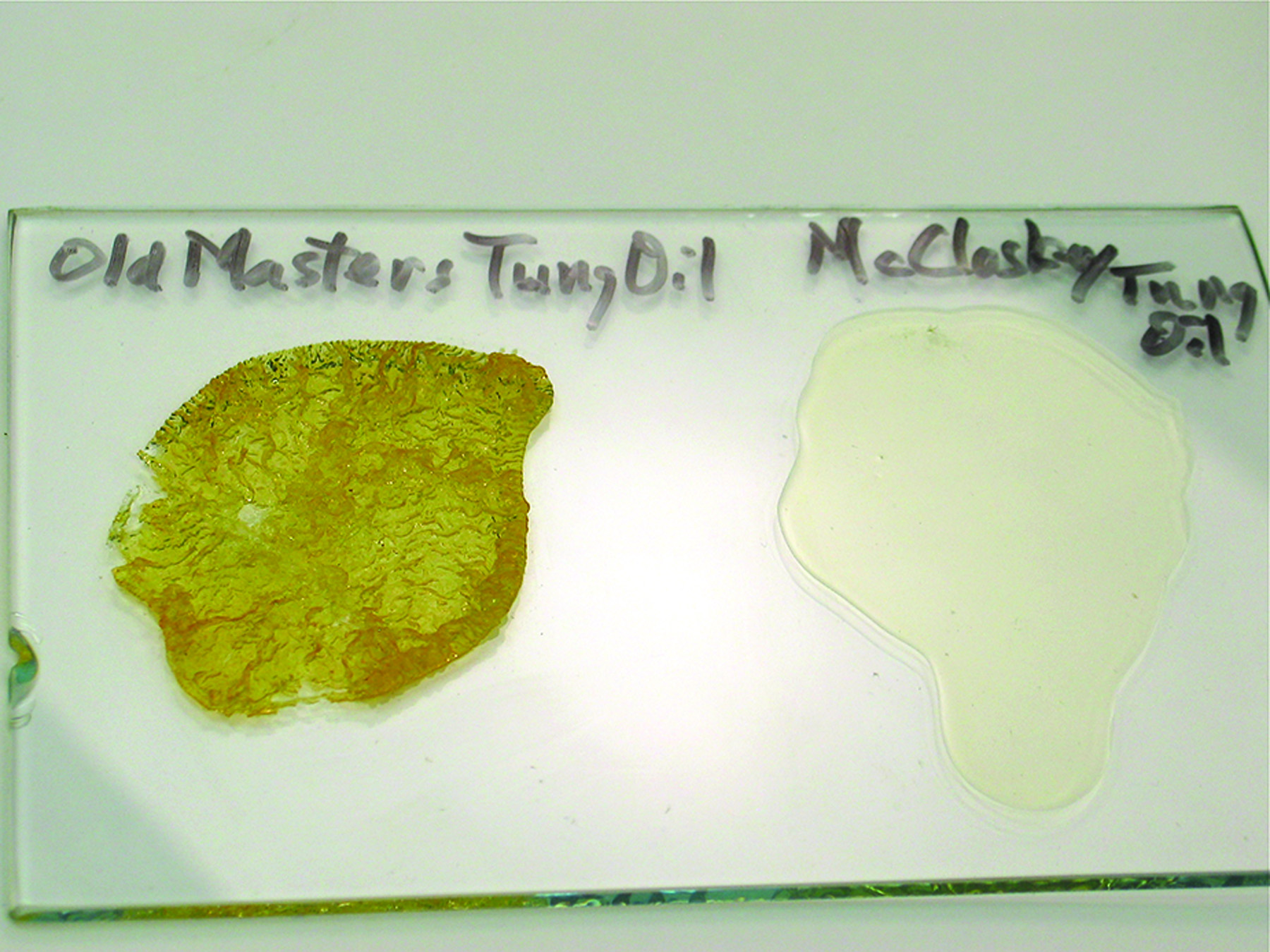

Two tung oils. Both of these products claim to be tung oil. Old Masters’ (left) clearly is. McCloskey’s (right) clearly isn’t. It’s varnish.

Tung oil is harvested from the nut of the tung tree, which is native to China but is now grown in other parts of the world. It’s more water-resistant than linseed oil and replaced linseed oil around the turn of the 20th century as the oil ingredient in exterior varnishes.

These varnishes, and all varnishes at the time, were made by cooking one of these oils with a natural resin, such as amber, copal or kauri, which are all fossilized sap from pine trees.

By the 1960s tung oil was being marketed as a complete finish in itself. But tung oil has problems. It dries considerably slower than boiled linseed oil, it doesn’t look or feel nice until five or more coats are applied and sanded between each, and it never gets hard, so no build can be achieved. Tung oil is not used very often as a finish.

To overcome the problems while keeping the positive-sounding exotic name, manufacturers began selling thinned varnish and oil/varnish blends and calling the product “tung oil.” This dishonest labeling has created all sorts of confusion in the marketplace and among writers who aren’t paying attention.

Polymerization Explained

Watco watermarks. Watco Danish Oil claims better protection because the finish polymerizes “in” the wood. Here, I left puddles of water on three coats of dried Watco for just more than a minute. It’s clear that resistance to water penetration is very minimal.

Some manufacturers claim their oils or varnishes “polymerize.” This is a big-sounding word that makes the finish seem special. But polymerization is simply the way all oils and varnishes cure when exposed to oxygen in the air. Individual molecules in the finish crosslink or hook up with each other chemically.

So the claim that a finish polymerizes is meaningless for distinguishing one oil or varnish from another.

The ingredient in oils and varnishes that makes them dry within a reasonable time is a catalyst called a “drier.” The drier speeds the introduction of oxygen, and thus the polymerization and curing. It’s the absence of a drier in tung oil that explains the slower drying.

The difference between raw linseed oil, which takes weeks or months to dry, and “boiled” linseed oil, which dries overnight when all the excess is wiped off, is the drier added to boiled linseed oil. Both oils polymerize.

One way you know there are driers in salad bowl finishes, which are wiping varnishes, is that they dry within hours.

Despite all oils and varnishes drying by polymerization, some manufacturers still try for an edge. Here are three examples.

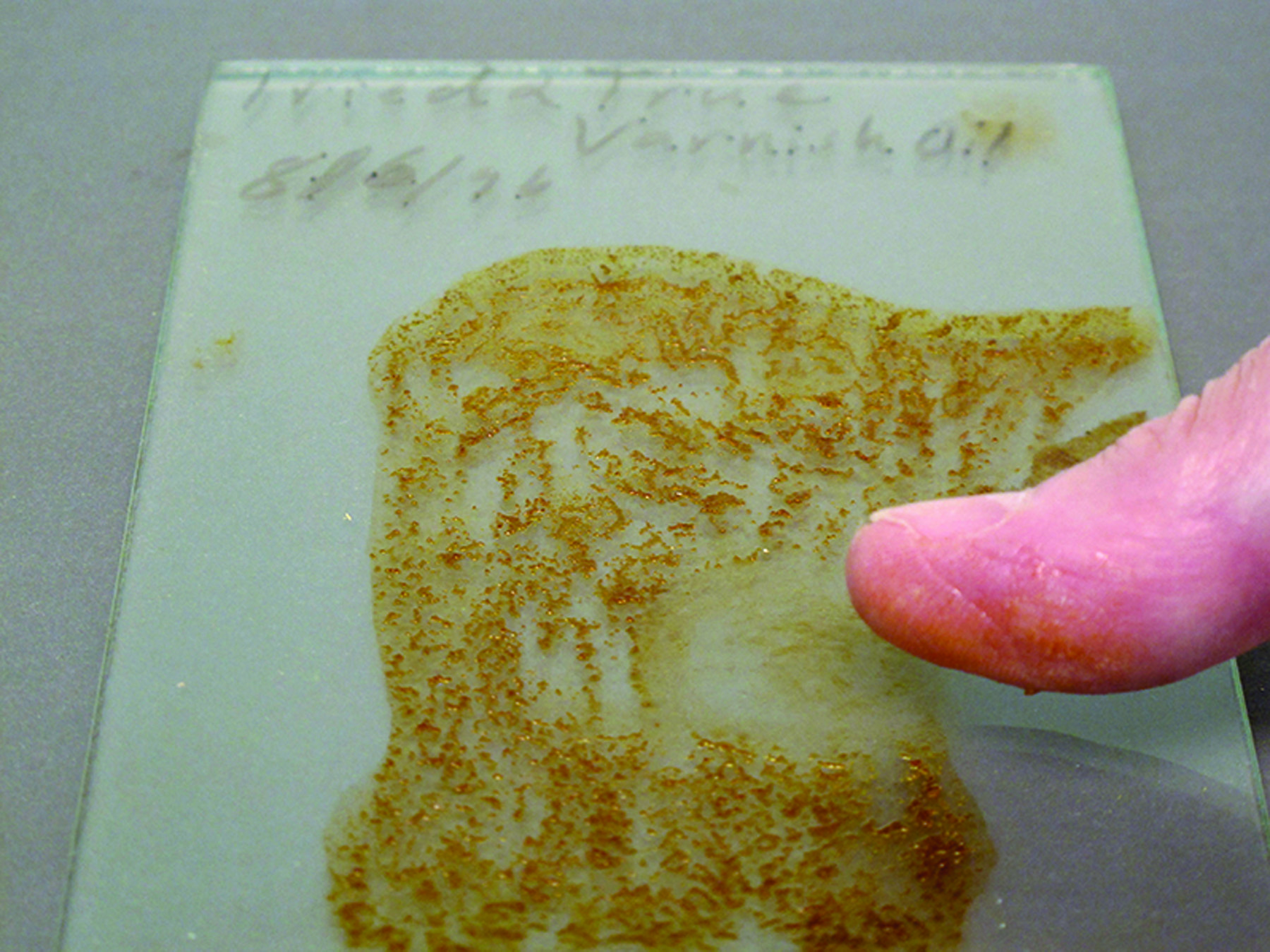

Very poor drying. Tried & True oil finishes are little more than raw linseed oil. Because I save almost all my tests, I still have a glass plate with Tried & True Varnish Oil, which has been exposed to air for 16 years. The finish is still soft and sticky.

Watco has long claimed that its Danish Oil polymerizes “in” the wood, implying better protection – that is, water resistance. Back in the 1970s I bought into this until I learned from sad experience that the important quality was how thick the finish is on the surface. Oil/varnish blends like Watco can’t be built up, so they aren’t very protective.

Tried & True oil finishes don’t contain driers, so they dry extremely slowly. They are essentially raw linseed oil. Why would anyone use such a slow-drying finish? Because the word “polymerize” in the marketing has made them think the finish is somehow better.

Southerland Welles also claims “polymerizing” to market its tung-oil product. But rather than simply exposing the raw oil to air for a while as Tried & True does, Southerland Welles cooks the tung oil in inert gases – no oxygen. So the chemistry of the oil changes. It thickens so much that it has to be thinned to be useful, and it dries very rapidly when exposed to air, even though it doesn’t contain driers.

Tru-Oil, marketed for gunstocks, is also this type of finish.

Resin, Drying & Hardening

Resin in oil. Varnish is not made by simply adding resin to oil. The two have to be cooked to change the chemistry. Here you see a piece of amber resin dropped into some raw linseed oil. The resin just sinks to the bottom, as you would expect.

So how do confused writers explain the differences in drying and hardening? They use the vague term “resin.” There’s oil, and the more resin added, the faster and harder the drying.

But you can’t just add resin to oil and change it. Think of dropping amber jewelry into oil. It will sink.

Varnish is made by cooking oil with a resin, including synthetic alkyd and polyurethane resins. This changes the chemistry, causing the finish to dry hard. It’s not the amount of resin used, it’s the cooking of the two substances that makes varnish.

So why not use the word “varnish” instead of “resin?” Everyone understands varnish. Why make something so simple so hard?

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.