We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

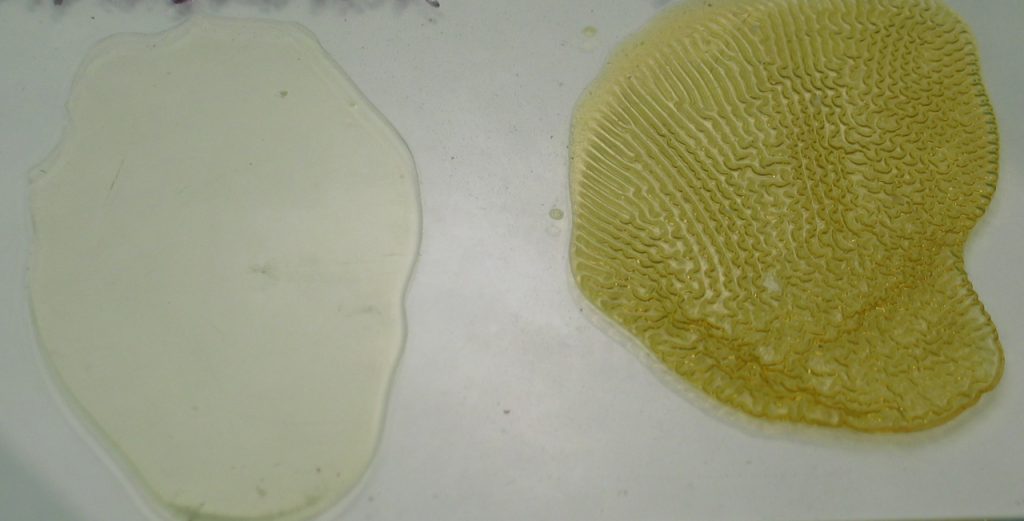

On the left is a dried puddle of wiping varnish. On the right is a dried puddle of a mixture of oil and varnish. Clearly a huge practical difference between the two.

If you go back to the early issues of U.S. woodworking magazines in the 1970s and ’80s and read about oil finishes, you’ll come away confused. The more you read the more confused you’ll become. I know this because I was there. The claims and explanations were all over the map. More often than not they were contradicting each other.

The problem of course began with the manufacturers and their labeling. What was Danish Oil? What was Seal-a-Cell? What was Waterlox? What was Salad Bowl Finish? For that matter, what was “tung oil,” when brands clearly performed differently? All of these were (are) wipe-on/wipe-off finishes, all are thinned and cleaned up with mineral spirits (paint thinner), and all are very popular with amateur woodworkers. But what are they? How do they differ?

In 1990, at the beginning of my writing career, Jeff Greef asked me to write an article on tung oil for Woodwork magazine (its archives are now owned by Popular Woodworking). I worked for three months researching that article during which the topic morphed into the broader subject of “oil” finishes in general.

I bought all the brands and followed all the directions, applying these finishes to various woods. Still confusing. The breakthrough came when a chemist friend suggested that I put puddles of the finishes on glass and see how they cure.

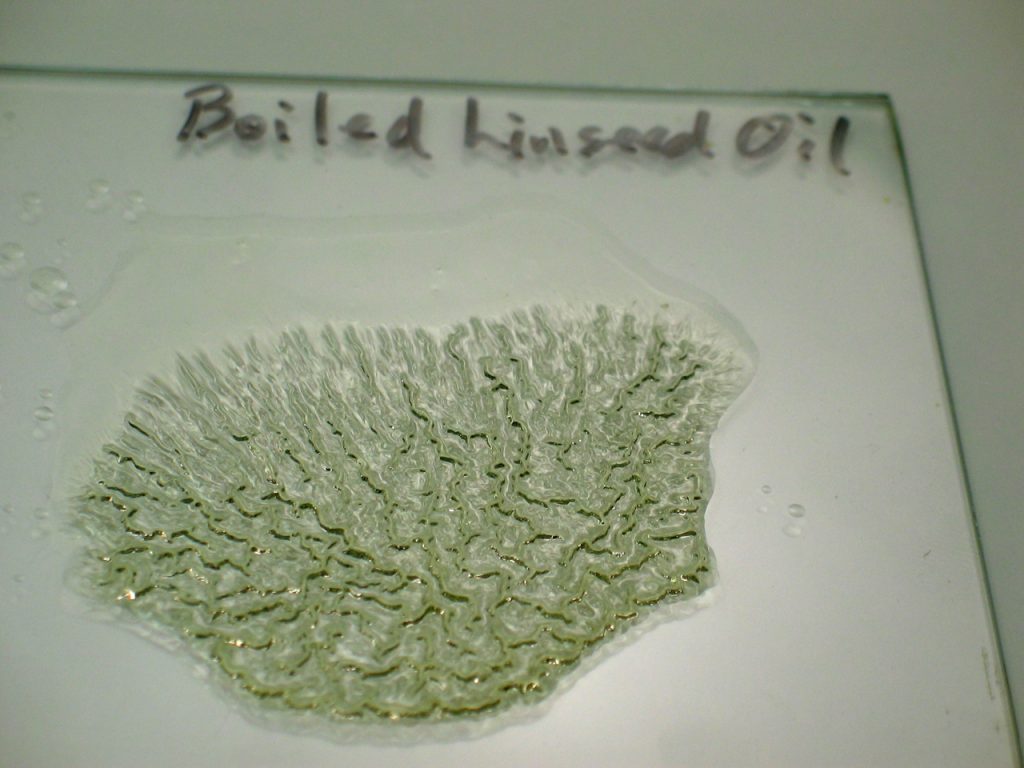

Voila! Some cured very slowly to a soft and wrinkled film. Others cured fairly quickly to a hard, smooth film.

As a reference, here is the way a puddle of boiled linseed oil cures on a non-porous piece of glass. Soft and wrinkled.

So there was a huge difference in these products. Some had to have the excess wiped off after every coat or the result would be a gummy, sticky mess. Others could be left damp or wet and built up to a hard film with several coats; this would provide much better water resistance. Some were obviously oil, or they were a mixture of oil and varnish because including oil with the varnish causes the finish to cure soft and gummy. Others were simply varnish, thinned with mineral spirits so the finish could be wiped rather than brushed.

Here’s where the confusion starts because varnish is made with oil. How do you define the difference between a mixture of oil and varnish (Watco Danish Oil, for example) and thinned varnish (Waterlox, Seal-a-Cell or Salad Bowl Finish), which is made with oil, other than by how they perform?

You can’t just mix a natural resin, in this case amber, with oil and expect to get varnish. The resin will just sink to the bottom and remain there. You have to cook the mixture to get the two to incorporate and make varnish.

The key words are “cook” and “mixture.” Varnish is oil and resin (think amber, used as jewelry) cooked to cause the two to combine chemically and make varnish. You can’t simply mix the two; the resin will just sink to the bottom and remain there. You have to cook it. (Varnishes are now made by combining chemicals and heating instead of combining natural products and heating, but the process is easiest to picture with the natural products.)

Once you have the varnish you can mix it with oil (linseed or tung) to make an oil/varnish blend. This blend acts like oil in that it never cures hard. The argument for mixing these, which you can do yourself if you want, is that the addition of varnish makes the finish a little harder and more water resistant than boiled linseed oil or tung oil alone. But my tests indicate that the difference isn’t much.

Never mind, there are still two very different products on the market represented as oil or unclear what they are.

Why did writing about this subject occur to me now, when I’ve written about it so many times before? Because I just received a woodworking magazine with an article that didn’t distinguish this difference. Varnish was defined as a “mixture” of oil and resin.

One of the things I’ve been most gratified about since 1990 is that woodworking magazines have all bought into my explanations and even adopted my term “wiping varnish” for thinned varnish to distinguish it from oil and oil/varnish blend.

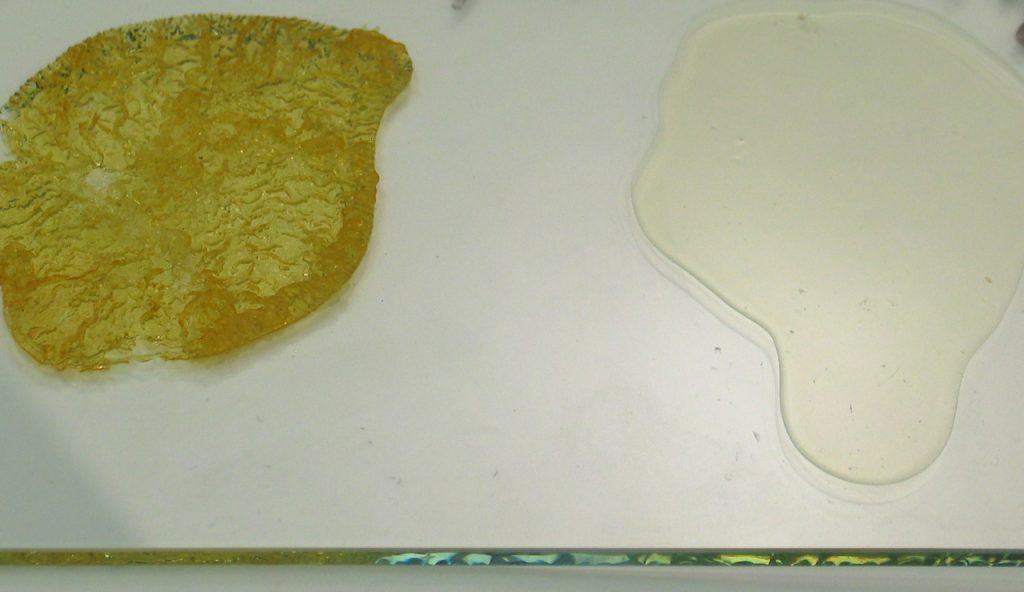

On the left is Old Master’s Tung Oil. On the right is McCloskey Tung Oil. Two well known companies selling two obviously different products, calling both tung oil. What could illustrate better why finishing can be so confusing?

OK, manufacturers haven’t budged a bit. They still mislead as they always have. But I have come to the conclusion that they don’t actually realize they’re doing this. They are marketing companies. As long as their products are moving off the shelves, everything is OK with the world.

The result of their not caring, however, is that the burden is on us to figure out what it is we’re buying. That’s what made it so depressing for me when I realized that here was a magazine that was still living in the 1970s and 80s.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.

Once an oil is converted into a varnish, do the inherent qualities of the oil remain? For example, raw tung oil is more water resistant, and cures more quickly, than raw linseed oil or soya. But once the tung oil is cooked with resins and dryers, is the resulting varnish any more water resistant than a soya based varnish cooked with the same resins and the same ratio of resins to oil? I ask because I am evaluating a few different varnishes for a kitchen table top that my kids will use daily. Waterlox (tung/phenolic), sutherland wells (tung/uralkyd), and Arm R Seal (which I think is soya/uralkyd). Should I care much what oil was used, or choose on the basis of color, cost, resin, and ease of application? Anectdotally, it seems that the tung based varnishes have shorter open time than the soya (which makes the soya easier to apply but harder to control dust), but maybe it is due to different dryers or resins.

Also, if you know of any other short oil tung/phenolic varnishes, please let me know. Waterlox is nice stuff by pricey for something that is 50% mineral spirits. It would be cheaper using something like epifanes and diluting myself, but I think that is a long oil and won’t cure as hard.

This article was timely for me, as I was deciding what to finish a picture frame I needed to deliver the next day when I read it. Thank you for all the information you provide, both here and in your books.

Jon

First I’d like to acknowledge this as being the best educational “finish” article I’ve read in Popular Woodworking. I have been selling a European line of finishing products which contain zero oils. In fact they believe they not only cause degradation to wood but also pose health hazards. Additionally oils cannot give a clean uniform finish.

You have pointed out an extreamly common marketing problem what is labeled on the outside of the can is not actually what really inside the can.Try convincing the person holding the can & reading the msds sheet the reality the glass proved. As KeithM said we should be like the textile industry & post detailed information in reguards to what truly is in our products.

I am glad to see this article. We are focused on our tools & equipment & many other new & improved systems of our trade yet we are still in the dark ages of finishing systems.

Too bad we don’t have requirements similar to textile fiber identification laws. You have to list composition, by percentage, using generic names, and can’t use terms like “wool-like nylon.”

One place I usually start is the SDS (MSDS) but sometimes they’re not helpful when they list “proprietary” ingredients. Sometimes I have to cross reference with CAS (Chemical Abstract Service) numbers to realize, “oh, that’s naphtha”

One of my recent favorites is “synthetic shellac!”