We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

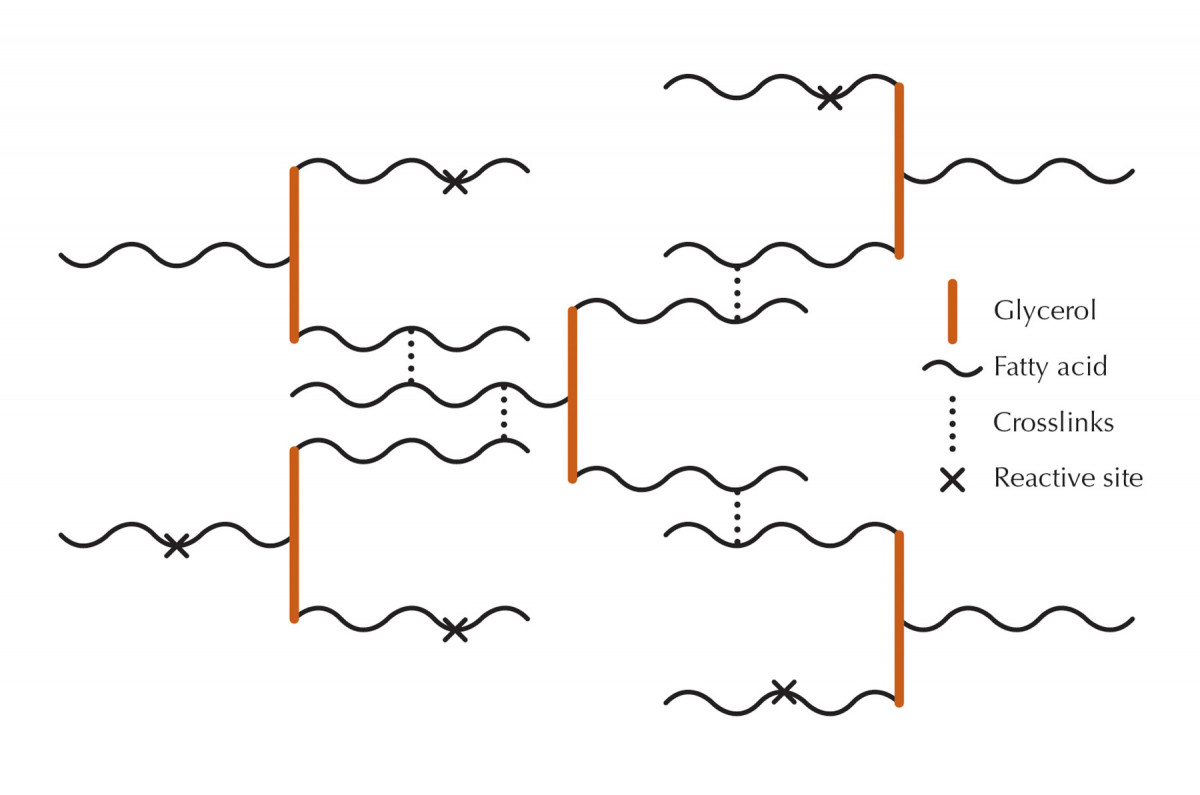

Tuning fork comparison. Vegetable oils are made up of triglycerides (glycerol molecules with three fatty acids attached). The tuning fork comparison makes these molecules easy to picture, but the actual fatty acids are curled up tightly and, of course, can’t be seen by the naked eye. The more reactive sites on the fatty acids, the better the oil cures – that is, turns from a liquid to a soft solid.

Learn why certain oils cure better and what makes an oil suitable for finish.

Oil is one of the most important ingredients used in finishing products. Besides being a finish all by itself, oil is an important component in varnishes, polyurethanes and furniture polishes; a primary binder in stains, glazes and pore fillers; a plasticizer in lacquers; and a lubricant used together with sandpaper or abrasive powders to level finishes and rub them to an even sheen.

Despite its importance, oil is poorly understood. To help make sense of it and understand how the various types differ, a little technical knowledge is helpful.

The Nature of Oils

You’ve probably noticed that some oils stay liquid forever while others get sticky after a while and still others dry completely after a day or two. The explanation is that some oils have more reactive sites than others, and it is at these sites that oil molecules crosslink and cure, usually with the aid of oxygen.

Oils that never dry have very few or no reactive sites, oils that get sticky have a few reactive sites and oils that dry completely have sufficient reactive sites to make this possible.

Oils have three large families: mineral oil, vegetable oil and synthetic oil.

Mineral Oil

Mineral oil is distilled from petroleum and is always a straight-chain hydrocarbon with no reactive sites, so mineral oil never dries.

If you apply mineral oil to wood, it continues penetrating into the wood until it can’t go any farther. So what you experience after each application is the surface slowly drying out and losing its rich color until eventually there’s enough oil in the wood to keep the surface in a semi-permanent oily state. (Washing the surface removes this oil, of course.)

Vegetable Oil

Stay safe. Linseed oil and any product containing linseed oil, including oil stains and glazes, can spontaneously combust if the heat created in the drying can’t dissipate. So if you work alone (rather than in a multi-person shop where safety protocols need to be established) and want to be safe with these products, drape rags over a trashcan or similar object, without piling them up, until they dry. Then throw them in the trash, which is no different than throwing an oil finished piece of wood in the trash.

Vegetable oils are pressed from seeds and nuts and make up the bulk of the ingredients in finishes. They are composed of a glycerol molecule with three fatty acids attached. This compound is called a “triglyceride,” a term you’re probably more familiar with in the context of blood tests and what is more or less healthy to eat. (Animal fats have the same chemical structure as vegetable oils, so they are also triglycerides.)

There are many different fatty acids, each containing from zero-to-four reactive sites per molecule. Sometimes all three fatty acids attached to a glycerol molecule are the same, but usually they are mixed, so the best way to figure the number of reactive sites in any given oil is to use averages.

Oils with fatty acids containing an average of zero-to-one reactive site per fatty acid don’t crosslink enough to ever dry. These oils, including olive, castor and coconut, are called “non-drying” oils.

(Oils without reactive sites are also called “saturated” and are unhealthy to eat because your body can’t break them down. Your body breaks oils down at their reactive sites, and oils that have them are called “unsaturated.”)

Oils with an average of one-to-two reactive sites per fatty acid dry better, but it takes a long time and heating the oiled surface is often necessary to help the drying along. Even so, these oils may still remain sticky, so they’re called “semi-drying” oils. Examples include walnut, soybean (soya) and safflower oil.

Oils with fatty acids containing an average of two or more reactive sites reach full cure, though slowly, and are called “drying” oils. The most common examples in finishing are linseed oil and tung oil. Curing occurs faster when heat is applied and also when metallic driers are added. These driers (often sold as Japan drier and composed of cobalt and manganese naphthenates) are catalysts that speed the introduction of oxygen into the oil.

The difference between linseed oil and tung oil can be explained quite easily by counting the reactive sites on their fatty acids.

Linseed oil has an average of about two reactive sites per fatty acid while tung oil has almost three. In addition, the reactive sites in tung oil are arranged better for curing. So tung oil cures faster than linseed oil, and it is considerably more water resistant when cured.

Keep in mind that the linseed oil we’re talking about is raw linseed oil – that is, without added driers. When metallic driers are added, making “boiled” linseed oil, the product cures faster than tung oil, which is never sold with driers added. Adding driers to raw linseed oil doesn’t make the final cure more water resistant, however. It just makes the oil dry faster.

Vegetable oils such as linseed oil and tung oil can be “polymerized” to make them dry faster, harder and glossier – resembling varnish more than oil. The method is to heat the oil to around 500ºF in an oxygen-free environment (in inert gases) until the oil begins to gel, then cool it rapidly.

Because there’s no oxygen, the reactive sites on the fatty acids crosslink directly (no oxygen atoms in between), so the characteristics of the oil are changed. When the partially cured oil is then exposed to air, it completes its drying very rapidly, considerably faster than varnish.

Linseed oil for color. Linseed oil has more orange color than most other oils and darkens as it ages. It can be used to deepen and enrich the color under other finishes, especially on darker woods such as the mahogany shown here. The coloring improves with age; it doesn’t happen all at once. Also, you have to let the oil dry completely before coating over.

Synthetic Oil

Synthetic oils generally don’t have any reactive sites, so they don’t dry. Silicone oil is probably the best known in the finishing world. This oil holds up to very high temperatures, so it’s often used to lubricate machinery. It’s also much slicker than mineral oil and has a lower refractive index, which creates more depth in finished wood. So silicone oil is often used in furniture polishes.

Fish eye. Maybe the biggest problem in refinishing is “fish eye,” where the finish refuses to flow out over a slick surface. This is caused by furniture polishes containing the synthetic oil silicone having been used for dusting; some silicone gets in the wood. In this case, the finish is polyurethane.

These polishes have received a bad reputation because the oil is so slick that it causes finishes to pull away forming “fish eyes” or craters. But these polishes are very popular with consumers.

Fish eye can be eliminated by cleaning the surface better with solvents or detergent, adding some silicone oil (sold as fish-eye eliminator or Smoothie) to the finish to lower its surface tension, or by sealing with shellac, which isn’t usually affected.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.