We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

Sixty-something year old George Wurtzel has turned porch posts for mansions, built furniture for R&B stars and crafted hundreds of kitchen cabinets. He’s run a cabinetmaking and countertop fabrication shop, worked as a Volkswagen repairman and taught industrial arts. He’s attended design fairs in Milan Italy and skied 500 miles across Finland. An impressive resume—made even more impressive by the fact that George is blind. “That I’m blind is no more challenging to me than a lefty trying to use right-handed scissors,” he explains. “You just need to use different scissors.”

Sixty-something year old George Wurtzel has turned porch posts for mansions, built furniture for R&B stars and crafted hundreds of kitchen cabinets. He’s run a cabinetmaking and countertop fabrication shop, worked as a Volkswagen repairman and taught industrial arts. He’s attended design fairs in Milan Italy and skied 500 miles across Finland. An impressive resume—made even more impressive by the fact that George is blind. “That I’m blind is no more challenging to me than a lefty trying to use right-handed scissors,” he explains. “You just need to use different scissors.”

Poor vision; great passion

“You’ve got to follow your passion in life regardless of the obstacles in your way,” George says. “Never allow someone who doesn’t have to pay the consequences dictate the consequences of your life.”

Computer Desk (2013); white oak, 48″ x 30″ x 18″.

George started life with poor vision and it deteriorated from there. But that never kept him from working with his hands. His grandfather, a carpenter and cabinetmaker, introduced George to woodworking. His father, an excavator, introduced him to mechanics. “Most kids had swing-sets in their backyards. We had backhoes, cranes and a thousand acres to play on.” But his mother, who grew up on a farm and was extremely creative, was the one who taught George that he could make anything. “On a farm you grow up learning how to do stuff—and she knew how to do stuff. It rubbed off on me.”

Dining Table (2013); white oak, glass, 29-1/2″ x 66″ x 36″.

George primarily attended schools for the blind, where he learned to read braille and navigate a world designed by and for sighted people. While attending one such high school—one that offered metalworking, woodworking and auto mechanics classes—George realized he was gifted with his hands. “Some people pooh-pooh schools for the blind, but I feel like I’m a better person for it,” he reflects, “because there was no one to tell me I couldn’t do something because I couldn’t see.”

Turned Vessel (2013); black ash burl, 6″ x 11-1/2″ x 10-1/2″.

After deciding to become a mechanic, George worked in Volkswagen and bicycle repair shops. But he didn’t like getting greasy, so he turned to woodworking. “Being the stubborn cuss I am, I just started building stuff,” he explains. “I built a few pieces of lawn furniture and put them outside. Within a month I got an order for a hundred chairs. I put a radial arm saw and a jointer on my brother’s charge card and I was in business.”

Piano Coffee Table (1978); walnut, 16″ x 36″ x 20″.

Business boomed for nine years. George’s shop expanded to 5000 square feet and eight employees. During this time, he built a piano-shaped coffee table. A one-third-scale model of a Steinway & Sons Model D concert grand, it was presented to Stevie Wonder—George’s former classmate—as an outstanding achievement award.

But when interest rates soared and the economy crumbled in 1982, so did George’s fortunes. He lost his shop, house and livelihood before deciding to relocate from Michigan to North Carolina. “You know you’re not doing so well when you can move everything you own on a Greyhound bus,” he recalls.

George applied for and was accepted into the Catawba Valley Community College Furniture Production Management program. The entry process was not without incident. “I walked into the admissions office with my white cane and the first thing the guy said was ‘We have a problem.’ I said, ‘Who’s we?’ He said ‘You’re blind.’ I replied, ‘I noticed when we shook hands that you were missing two fingers.’ He explained he’d lost them in a woodworking accident. I told him that all I was looking for was the same opportunity to cut off my fingers that he’d had, and I got in!”

Reproducing architectural millwork is one of George’s specialties.

While finishing his course work George was hired to set up a cabinet-manufacturing shop. He designed the space, bought and set up all the machinery, and wound up managing the facility, which produced up to eight kitchens per week.

Flag Case (1989); walnut, 4-1/2″ x 22″ x 18″.

A few years later he went back into business on his own, naming his new company SellAmerica. “I wasn’t sure what I was going to make, so I figured a name like that would allow me to sell anything,” he says. George designed a triangular display box for veteran interment flags and established accounts with 2500 funeral homes and the armed forces. He eventually sold the company and spent the proceeds on “drugs, sex and rock and roll—and the rest foolishly.” For a while he dabbled in raising horses, worked in a bakery and ran a camp for blind kids.

In 2009 George moved to Minneapolis to work as an industrial arts teacher for an organization called Blindness Learning in New Dimensions (BLIND). He enjoyed working with students facing the same challenges he had faced. “But you know,” he explains, “when you work by yourself for a long time, you like to do things your own way.” In 2011, he again dove headlong back into the furniture-building business, this time concentrating on a line of puzzle furniture.

Designing without erasers

George’s puzzle furniture is based on the interlocking wood puzzles his grandfather made for him when he was a child. The furniture has a Craftsman-style look and feel. Designed for people living an “urban, nomadic lifestyle,” it can be easily assembled, disassembled and moved. Each piece is held together with a single fastener—a hidden thumbscrew. George has applied the basic design to create coffee, end and dining tables, as well as bookshelves and a laptop desk that adjusts for standing or sitting.

Box-Joint Cube (2013); pine, walnut, 4-1/2″ x 4-1/2″ x 4-1/2″.

The joinery is complex and precise. As with all of his pieces, George designed everything in his head. “Good design can be felt, not just seen,” he explains. When asked about the challenges of designing cerebrally rather than on paper, George says, “Creativity doesn’t come out of your eyeballs; it comes out of your head. Some people are blessed with the ability to sing, some with playing baseball. I’ve been blessed with the ability to see everything in my mind’s eye. When I’m designing something I can look at it from every angle by rotating it, using my brain’s built-in computer mouse.” George maintains most people design with a pencil because there’s an eraser on one end. “My eraser is the scrap bin,” he jokes.

Working in darkness

George’s shop looks like any other woodworking shop. It sports a drill press, miter saw, bandsaw, half a dozen routers and stacks of wood. A huge lathe—large enough to turn porch posts—occupies one corner. As George lives in an older part of Minneapolis, he’s recently found a niche reproducing architectural millwork. He turns delicate sculptural vases and bowls on the same lathe.

George calls his Felder multi-machine a “poor-man’s tool,” because, “after you pay for it, you’re poor!”

A massive Felder multi-machine that incorporates a shaper, jointer, planer and rolling-table saw occupies the center of George’s shop.

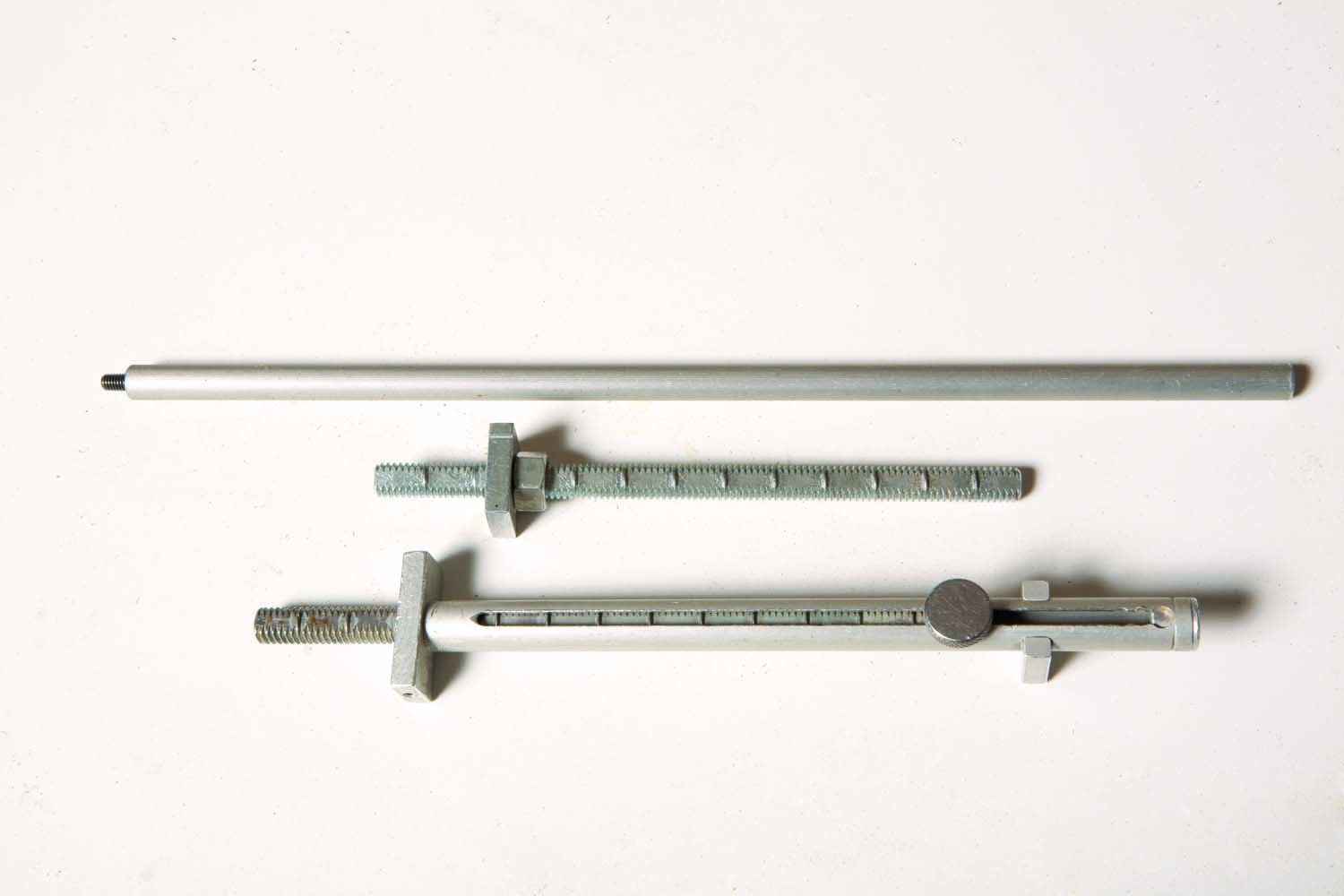

The one tool that might look foreign to most woodworkers is the small “click ruler” that George keeps in his back pocket. The heart of this device is a 12″ long 16tpi threaded rod with one side flattened and scribed in 1/2″ increments. This rod slides inside a tube that has a stop at one end and a spring-loaded ball bearing located precisely 6″ away. Each time the ball bearing engages the next thread, it clicks—indicating a 1/16″ change in dimension. By engaging the stop and adding together the 6″ fixed dimension, the number of exposed 1/2″ scribe marks and the audible clicks, this ruler measures up to 12″ in 1/16″ increments. Screwing on additional threaded rods extends the tool’s capacity in 12″ increments. To measure in 1/64″ increments, George uses a “roto” ruler, which is based on the same threaded rod. This ruler simply has an adjustable nut with a square head. Each quarter turn of the nut measures 1/64″.

George uses two rulers for precise measuring. His “click” ruler makes an audible sound with each 1/16″ change. Each quarter-turn of the square-headed nut on his “roto” ruler marks 1/64″. Adding one or more extension rods increases the range of both rulers.

George uses a scribe for marking, rather than a pencil, so he can feel the lines. Two other tools he’s fond of are the audio-output tape measure that he uses for rough measurements and the push-button remote that allows him to control his dust-collection system from any place in the shop.

George doesn’t use a blade guard on his tablesaw. Because he works primarily by feel, the guard continuously gets in the way. Yet, after 40 years of woodworking he still has 9-7/8ths of his fingers; he nipped one while doing a repetitive task at the end of a day. We’ve all been there.

As a person who “sees” with his fingertips, George doesn’t understand people who focus on how a piece of furniture looks and ignore how it feels. When it comes to sanding and finishing, he’s a perfectionist. “Don’t be in a hurry,” he explains, and then adds—with a twinkle in his eye, “If it’s worth the effort to build it, it’s worth the effort to sand it.”

Some people feel a piece of furniture or wood art should stand aesthetically on its own; others feel a greater appreciation can be gained by understanding the era in which it was created or knowing who created it. George’s furniture and turnings surely stand on their own, but knowing the man—and his story—makes them even more special. And yes, George’s eyes do twinkle.

Sidebar: A Special Project

George’s most recent project reflects his creativity and compassion. He met Maire (pronounced “Mary”) Kent through Keith Famie, a filmmaker who’s producing and directing “Maire’s Journey,” a feature documentary. Maire was enamored by the children’s book Paddle to the Sea, but having been diagnosed with advanced cardiac sarcoma, realized she wouldn’t be able to trace the journey of the book’s main character while she was alive.

Maire died at the age of 24—but not before she and George met face-to-face to discuss an idea—building a sailboat that would allow her to complete the journey in the afterlife. This vessel would carry Maire’s ashes to the sea, following the route described in the book. Based on her wishes, George crafted a prototype and tested its seaworthiness using bags of sugar as surrogate ashes. Then he built Maire’s boat.

This summer, Maire’s boat will be launched from Northern Michigan with the goal of making its way through the Great Lakes “to the sea.” This message from Maire will be painted on it: “My name is Maire Kent. I died of sarcoma cancer. I’m making my way to the ocean. If you find me, please set me back on my path. I will bless you from heaven.”

Keith and his Emmy-winning production company Visionalist Entertainment Productions will film the voyage, documenting how people react to Maire’s custom-built vessel and the journey she’s on. “We’re not sure when the boat will reach the ocean,” George explains. “But we know two things: First, we want it to travel down the Detroit River during the fireworks celebration on the Fourth of July. Second, it’s definitely not sturdy enough to go over Niagara Falls.”

For more information about “Maire’s Journey,” visit v-prod.com.

To see more of George’s work, visit gmwurtzel.com.

Spike Carlsen is the author of Woodworking FAQ and other books. His newest, The Backyard Homestead Book of Building Projects (Storey Publishing), is now available. For more information, visit spikecarlsen.com.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.