We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

Designer and builder of elegant but simple iconic furniture.

Editor’s note: This piece was originally published in the December 2009 issue of Popular Woodworking in memoriam of Sam’s passing that year.

Sam Maloof is the reason I became a furniture maker. I used to teach shop in the early 1970s. The Portland (Ore.)Public Schools maintained an audio/video depository for teachers and in those days most of the technical choices were film strips with the requisite recording that beeped when it was time to roll forward. Dorky. The heat from the projector was unbearable.

My woodshop “classroom” was small and consisted of a series of tiered benches surrounded by windows reinforced by chicken wire – a needed safety measure to protect students from the occasional explosions in the adjacent welding lab.

Sometime in 1974 I noticed a film titled “Sam Maloof: Woodworker” and ordered it for review. The next day after classes, I rolled in the projector and watched a movie about a woodworker who was unknown to me. It is probably important to mention that I was 23 years old and 1,800 miles from home.

Time erodes my memory, but I believe the film was around 30-40 minutes in length and I watched the film five times in a row. It was the most humbling experience of my life. Here I was teaching woodworking and realizing that I knew nothing about woodworking.

Produced by Maynard Orme (who later served 19 years as the president and CEO of Oregon Public Broadcasting), “Sam Maloof: Woodworker” was impossible for me to ignore. I remember a raging internal debate as to whether I should show this to my students for fear of exposing my own ignorance. But I could not keep this from my kids.

I have now seen that film well over 50 times and have learned something with each viewing. At that time, I did not know about pattern shaping, never had seen a rolling pin sander, and it never occurred to me that wood could be sculpted in such fashion. I hate to admit it, but at that time I was Forrest Gump-dumb in regard to woodworking – probably everything else too.

Within a year another film made the catalog, featuring Wendle Castle’s music rack (can’t remember the title). It was a cool how-to film set to Modest Mussorgsky’s “Picture at an Exhibition.” Then in 1975 I received the first issue of Fine Woodworking (which I still own). I did not know it at the time, but my life was being swept up in a woodworking tsunami that spanned the entire planet. I don’t think we will ever see a wave this big again.

It was early 1978 when I noticed an ad in Fine Woodworking for the Anderson Ranch in Snowmass, Colo. Listed was a three-week summer hands-on workshop with … Sam Maloof!

It was dusk when I pulled into the Anderson Ranch and while driving into campus I noticed a barn with doors wide open. Alone inside was Sam Maloof oiling a rocking chair. I was such a star-struck wimp that I quickly sped past to the check-in counter for chickens.

The Anderson Ranch woodworking classroom was two columns of workbenches. I took the very last bench because I would not like to look around, or over, a 6’3″ awestruck fellow like me who hogged the view.

On the third or fourth day an interesting thing happened. Sam’s glasses broke at the bridge and for the rest of the class, they were held together with white tape – Hanson-brother style for you hockey fans.

The significance of this event was transformative for me because I then realized Sam was just as susceptible to life’s quirks as the rest of us. I also noticed that he worked fast. Really fast.

One of my fondest memories of Sam is from that class, in which I made my first scooped chair seat. I was so excited and was eager for Sam’s approval when I thought my chair was ready for oiling.

“It will be fine when you get all the bumps out.” He informed me, as I wondered how his stovepipe fingers could feel anything. “What bumps?” I asked; it appeared perfect to me.

“Are you right- or left-handed?” Sam asked. “Left,” I said. “Put a pencil in your left hand, close your eyes and feel the seat with your fingertips. Every time you feel a bump, color it with the pencil with eyes closed. Dents are bumps on all sides. Do this until you think you are done. Do not open your eyes, and use all ten fingers.”

When I opened my eyes my chair seat was almost entirely black. I was not only shocked, but really discouraged. I scraped all the marks off, and repeated the process five or six more times. In the end, when the finish was dry, it was easy to see the grace and flow of the sculpted seat. It made the light sing; the work was not only worth it, but its own reward. It was then I knew furniture making was for me.

When Sam left my station after sharing what I needed to do, he reminded me that you are half done with a piece when it is ready to sand. That also was an eye-opener. I then realized that you are not green forever and that this class with Sam Maloof would change my life in unimaginable ways.

Finally, I raised my hand again. Sam came by, ran both of his hands over my chair seat, smiled, and walked over to another student. It was the best day.

On the last day of class there was a picnic. Sam sought me out and apologized for not spending much time with me. It was a grand gesture, sincere and he really did feel bad. I told him I was not there to talk but to learn and that I was going to go home and quit my job to be a furniture maker. It was the easiest decision I ever made.

Before we parted company Sam asked to see my portfolio. All I had were a couple pictures of a try-square I designed for my beginning woodshop classes – I was really embarrassed. In his customary way, he told me he thought the try square was beautiful.

Within a couple of years my work – strongly influenced by Sam’s forms – was being accepted by juries. At some point Sam called to congratulate me and I confessed how hard it was to design without thinking about how Sam would do it. He told me not to worry, that this will pass and I will find my own voice. It was not long before I had a three-year backlog of work and just as Sam predicted, my later work bore no resemblance to his own.

I never once saw Sam wear a dust mask, and neither did I. My furniture-making career came to a quick halt in 1983 with a hyper-allergic reaction to wood dust. Bridge City Tool Works was my last shot at self-unemployment.

A couple of times a year there would be tool shows in the Los Angeles basin and I would stay with Sam and Freda on their lemon grove property. We would talk until Freda made Sam go to bed. It is here that I learned that objects should be worthy of the space they occupy – Sam surrounded himself with the visual richness of others in addition to his own work. There was a canoe hanging from the ceiling – how cool.

Customer and Friend

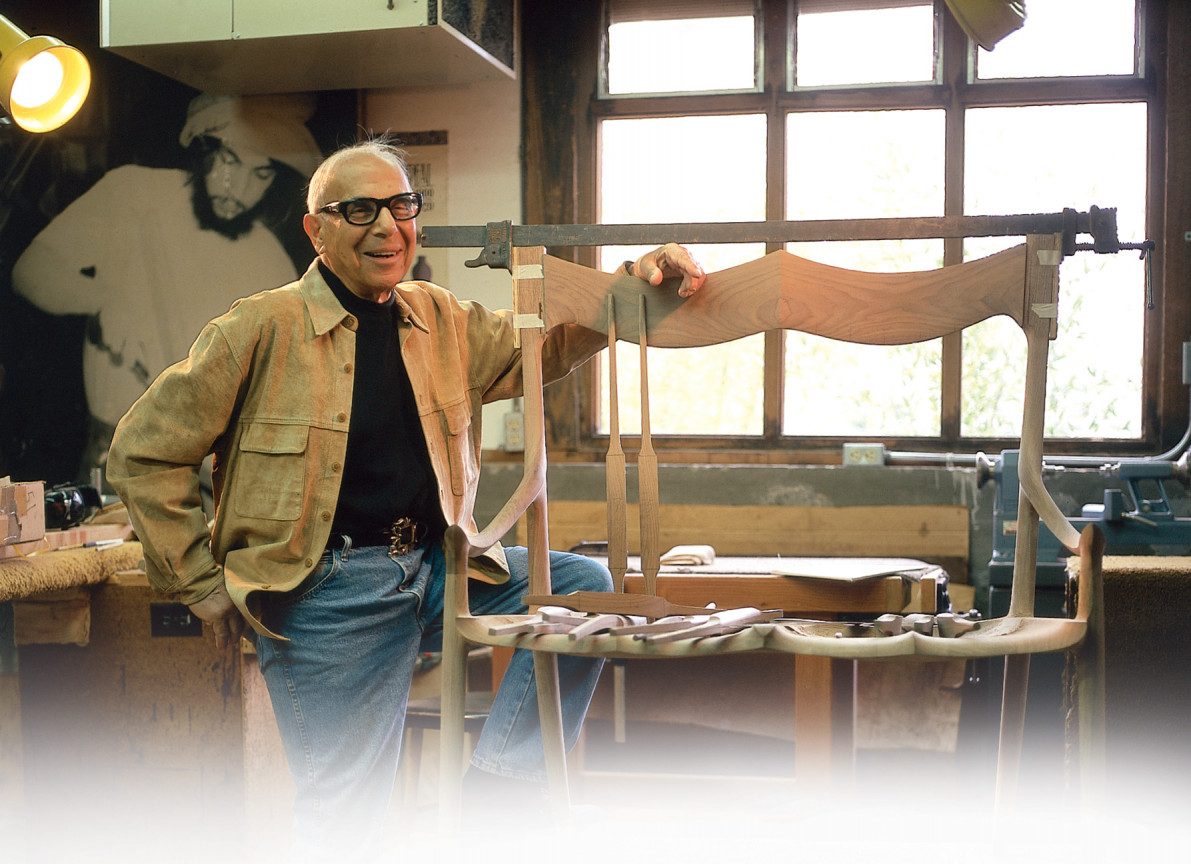

Legendary rocker. The iconic Maloof rocker has been made for presidents, celebrities and captains of industry. Maloof used templates to guide the rough work, but allowed the final form of each rocker to change in response to the wood.

Sam was an avid customer of Bridge City and during one trip I asked him where all the tools were that he had purchased. They’re right here behind the sofa, he said, and he pulled out a box and opened it. I said, “Why don’t you use them?” “I do,” he replied. “I tell everybody about these beautiful tools.”

Craftsmanship meant a great deal to Sam and I will never forget it. The ego will let your eyes lie, but your fingertips never will. To this day, when I teach, I explain that if something is supposed to be flat, then it better be flat because the light will expose your intent as flawed.

And if you allow these sorts of compromises then the honor of calling oneself a craftsman cannot be done in good faith. I learned that anybody can do mediocre work but fine work, well, this takes dedication, understanding, patience and desire. Making something worthy of the space it occupies is not only hard, it is imperative. This lesson has been the driving force behind Bridge City tools for the past 25 years.

My last visit with Sam was a year ago; I took Sam and “the boys” to lunch. Sam asked to see our latest tool, which was the CT-14 Shoulder Plane. When I told him the price, Sam commented, “$800 is a lot of money for a plane.” I retorted, “$35,000 for a rocking chair is a lot of money for a piece of furniture.”

One of the boys interrupted: “Sam, you are not going to win this one.”

And with a wink, he put the handplane on his lap and asked if I could send him an invoice.

I don’t believe Bridge City would exist without Sam Maloof. And like so many others, I desperately wish he were still here.

Thanks Sam. –John Economaki, founder of Bridge City Tool Works.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.