We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

In his element. Chris Vesper’s small shop and home are filled completely with old tools, his machinery and his book collection.

Chris Vesper strives for precision and perfection in toolmaking (and dancing).

Editor’s note: this article originally appeared in the December 2013 issue of Popular Woodworking

When it comes to settling the issue of who is the most dedicated toolmaker on the planet, Chris Vesper has the plumbing – or rather, the lack of it – as proof of his single-minded love of the craft.

Several years ago, Chris built his 12 x 8-meter shop and home on the land behind his parents’ house in rural Somerville, Australia. After carving out space for his extensive collection of machinery, a bedroom and kitchen, he had to make a choice: Should he make space for his tool collection or should he build a bathroom instead?

Smiling, Chris pulls open a huge metal drawer filled with the largest collection of unusual chipbreakers and irons I have ever seen. Above that drawer are stacks of vintage and rare hand tools he studies. Behind is his collection of rare books and his prototypes.

Yup, the tool collection won.

So Chris takes showers at his parents’ house. When visitors arrive, he shows them the particular trees where it’s good to do your business.

“Just wave to the neighbors if you see them,” he says.

Among all of the passionate toolmakers working today, few can match Chris for his intensity, his attention to detail and his insistence on doing every operation himself. His demeanor has earned him a reputation as somewhat of an outlier.

When I first arrived in Melbourne, Australia, one of the woodworkers I met asked me: “Have you met our very odd Mr. Chris Vesper?”

Showing up. Chris attends woodworking shows both in the United States and Australia, such as this weekend show in Melbourne, Australia, in 2013.

The funny thing is that while Chris is an incredibly focused person, he also has a genial side that few of his customers see. He loves salsa and ballroom dancing – in public and with groups of people.

“I’m aware I’m pedantic,” he says with a laugh. “But I’m pedantic with my tools, and I keep a clean workshop. I wash my car only once a year, and there are times when I let the dishes pile up. I focus my fussiness on what I want to do.”

Indeed, after spending a couple days with Chris in his workshop, you can see that he is more than just a talented machinist. In his own shop, he is completely at ease, moving around with surprising fluidity amongst his surface grinders, milling machines, metal lathes and workbenches (it is a bit like dancing).

He cooks a mean breakfast, is still unmarried and has an eye for the women at coffee shops.

But when the conversation turns to tools and his machines, he is all business and precision and microns.

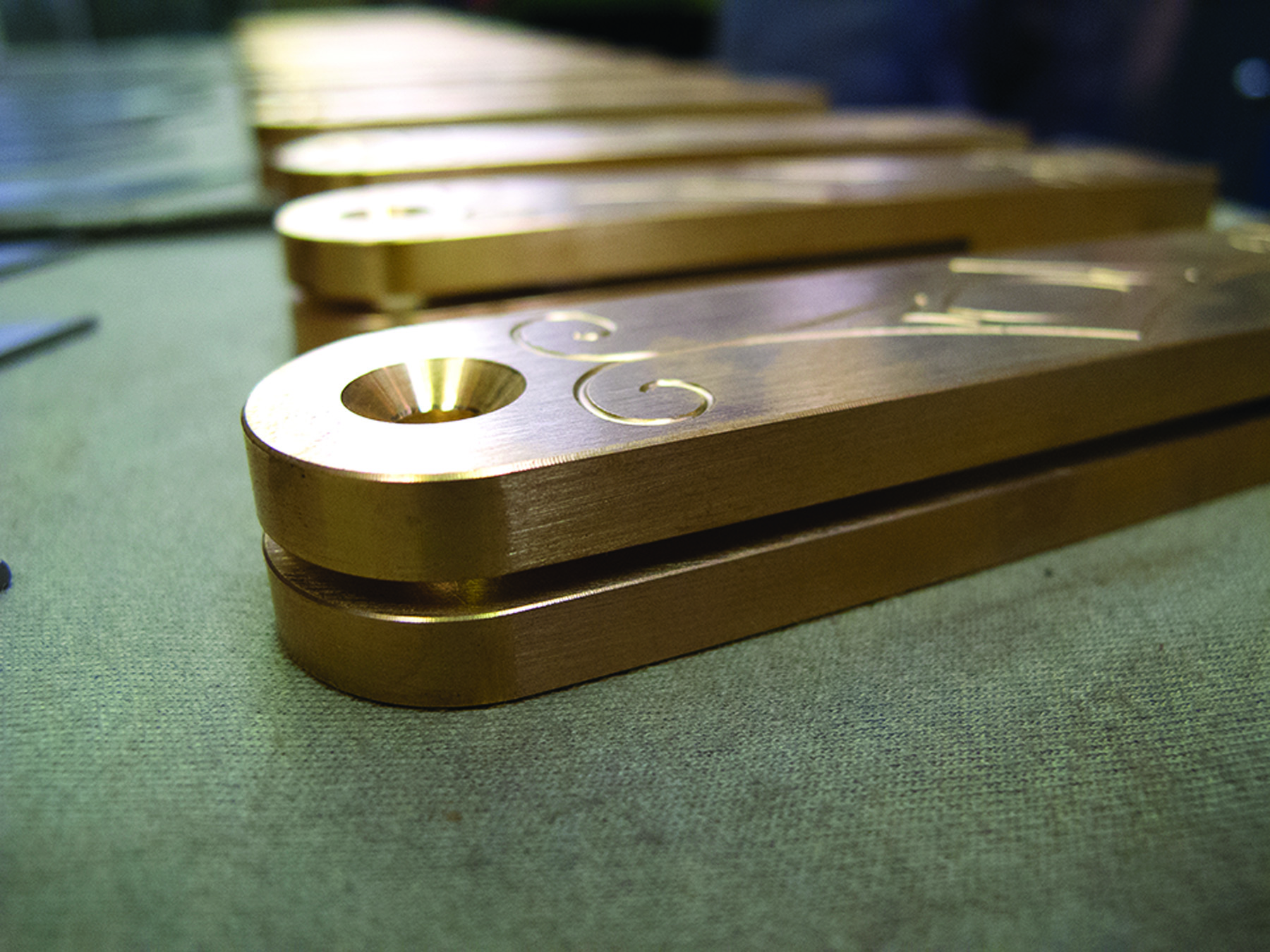

Ready for assembly. Here are some engraved parts for bevel squares, ready for assembly.

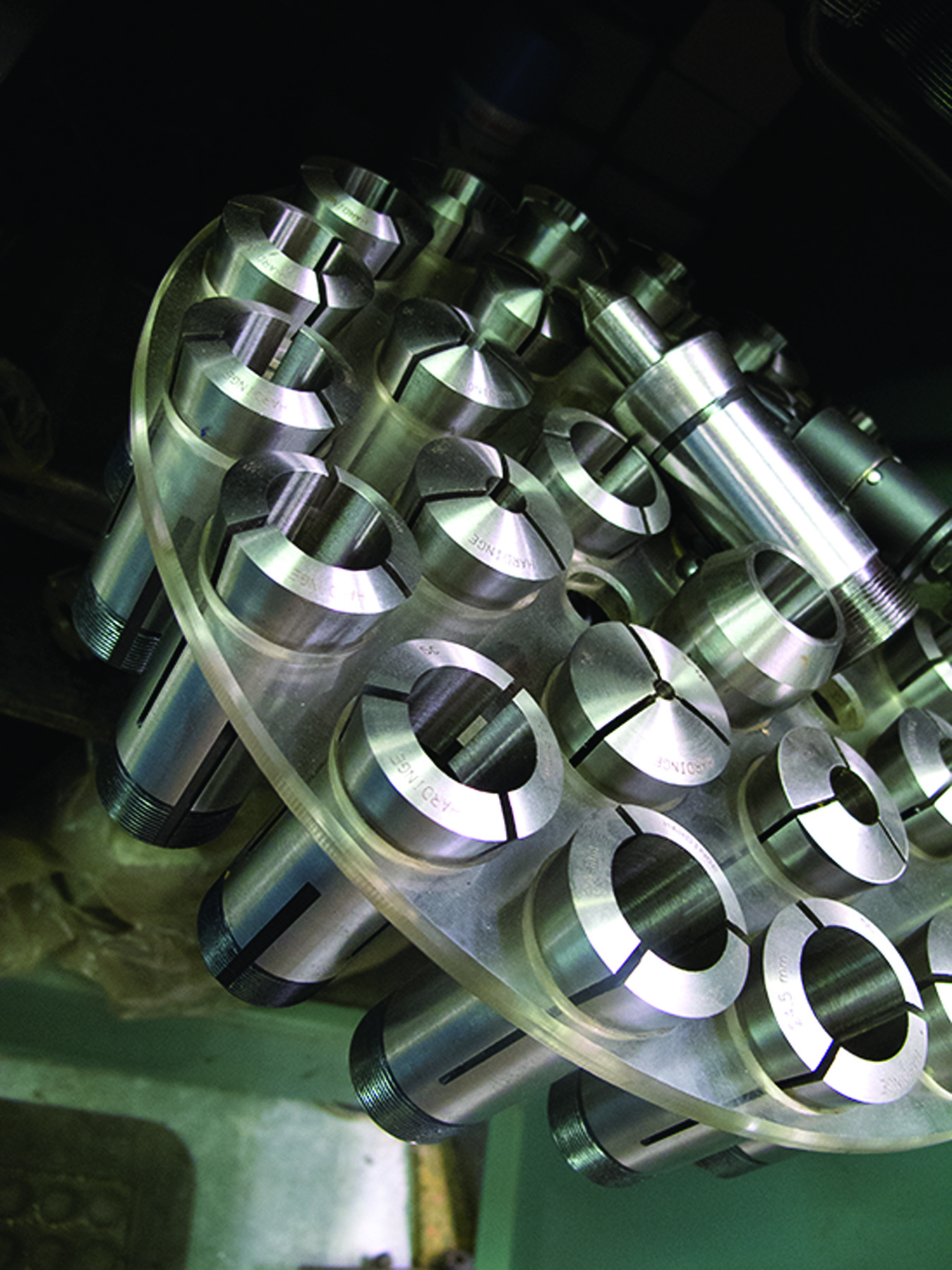

Most of the machinery he uses to make his bevels, squares, marking knives and other tools was purchased used and restored by Chris to factory-new. For many years, he poured all the profits from his business into his machinery and tool collection.

As a result, he has machines that few individual toolmakers own – including several large surface grinders, a large milling machine, hardness testers, a Mitutoyo profile projector for part inspection, a laser engraver, a Feeler toolroom lathe – and the list goes on.

Miller at work. Chris mills the bed of one of his customer’s planes during a workshop in March.

The results of the machinery and Chris’ training pretty much speak for themselves. His sliding bevels are, in my opinion, without equal. They lock tighter than any bevel I’ve ever used. The fit and finish of the parts is top shelf (or perhaps the shelf above the top shelf). And his metal try squares are good enough to be used for precision toolmaking, as well as woodworking.

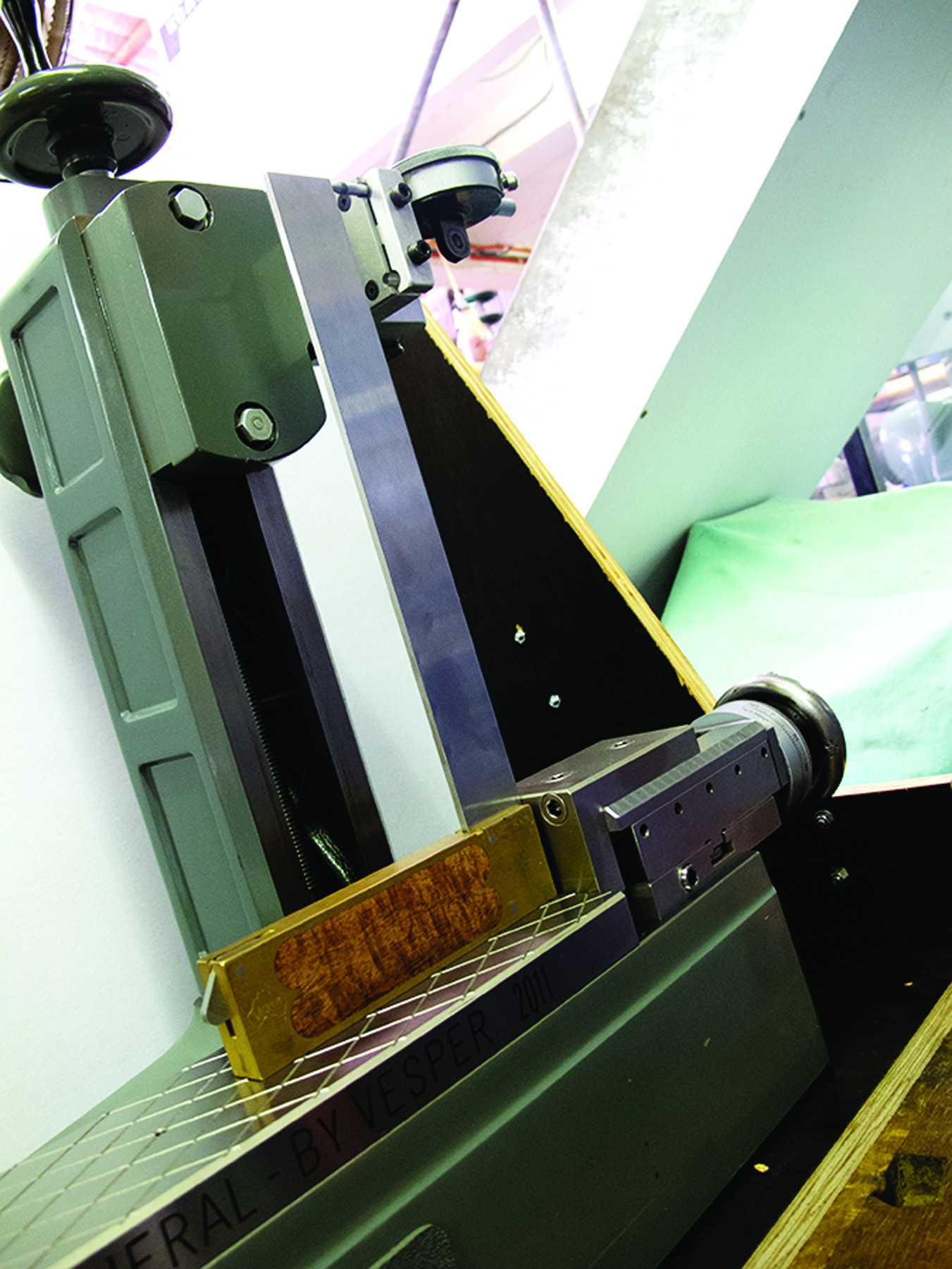

He checks every square on an ingenious apparatus he built himself in 2011 called “The General,” which remains under a cover most of the time to protect it from dust. The most accurate squares he makes are accurate within 10 microns. (For reference, a human hair is .0035″; a micron is .000039″.) These squares are labeled “A+” and are used by other toolmakers and woodworkers who are demanding (read: engineers).

For turning parts. One of the more impressive machines on Chris’ shop floor is his Feeler toolroom lathe (above) and the chucks he has collected for it (below).

While some woodworkers gritch about the prices he charges for his tools – a 7″ sliding bevel can run about $239 – I always say: compared to what? There’s really nothing else out there that can compete with his bevel.

Chris has carved out an incredible little world for himself, both in the woodworking world and in his parents’ backyard. You have to ask: Where did this guy come from?

Chris has carved out an incredible little world for himself, both in the woodworking world and in his parents’ backyard. You have to ask: Where did this guy come from?

Two Apprenticeships

Early work. Chris used to make this infill shoulder plane for sale. Now he concentrates on his marking and measuring tools.

Chris started as a self-taught woodworker at age 15 who couldn’t afford his own tools. He wanted to become a full-time furniture maker, so he decided to make his own tools, including a mortise gauge, a cutting gauge and some planes.

And in this drawer. Chis is a tool collector, user and maker. His collection of blades and chipbreakers is impressive.

At school, he took the woodworking classes that were offered, but he was too young to use the machinery, except the lathe and the disc sander. Plus all the tools were dull.

After finishing school, Chris got an apprenticeship as a fitter and a turner, but he completed only two years of the four-year program.

“My competitive and perfectionist nature really stressed me out,” he said.

So he took a cabinetmaking apprenticeship for a while and left that after nearly two years to work in the trade for other people. It became apparent that he wasn’t ever going to be promoted in these shops and Chris says he was tired of working for other people.

“I can remember the time after leaving my last job when I got down to my last $5,” he says. “Scary.”

He began his business, Vesper Tools, in 1998 and started by making marking gauges and carving knives, which he sold at Australian woodworking shows. A few years later he started making his current crop of sliding bevels after seeing a 19th-century patent drawing for a bevel with a tough butt-locking mechanism.

‘The General.’ Every try square Chris makes is checked for accuracy on this device, called “The General,” which Chris made.

Chris even made a few infill shoulder planes for customers. I saw two of them while visiting Australia– they’re beautiful – but he doesn’t plan on making more.

He doesn’t have any employees and he makes every tool himself. The process begins behind his shed in one of the two giant metal containers parked there (by the “bathroom”). One container is filled with vintage machinery he plans to restore, including an old printing press. The other container is filled with wood. Stacks and stacks of the gorgeous and difficult woods he uses to make his tools – Tasmanian blackwood, ringed gidgee, conkerberry and black red gum.

The wood is slabbed up on his 1870s Western & Co. Darby & London band saw (nicknamed the “bandosawrus”). And then he gets to work on the metal parts with the milling machine and surface grinders.

World headquarters. Chris built his workshop and home in the back yard of his parents’ home in Australia.

When the tools are complete, they are stored in the “panic room,” a climate-controlled room upstairs that also could have been a decent bathroom. He sells his tools direct to his customers for the most part through his web site and at woodworking shows.

It’s a full life – building tools, selling them and filling in the spare moments with dancing, collecting old books, music and cooking. What more could he ask for?

“I would like to be married,” says Chris, who is 33. “Finding the right girlfriend has been tough.”

Fixing that problem won’t require a new milling machine or demagnetizer, but it just might require some additional plumbing at Vesper world headquarters.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.