|

Years ago, an old professional spindle turner

showed me a different way to sharpen

a skew. When I tried it, I was sold. This

modified grind is more versatile, friendlier and

more responsive than a traditional grind. Used

correctly, a modified skew is difficult to catch and

dig into the wood, unlike a conventional skew. In

the years since, I’ve found that many early 20th century

turners from Maine to Indiana adopted

the same alternate shape. They were all on to

something good.

It’s easy to learn how to sharpen a modified

skew. I’ll show you how to take a regular skew chisel

with a flat cross section and turn it into a far

superior tool in an hour or so.

Shape the sides

Begin modifying a conventional skew by reshaping its

sides (Photo 1). I prefer to do this on a belt sander

mounted in a stand and equipped with a belt designed to

cut metal (see Sources, below). Be sure to remove all

the dust from the sander and set aside its bag to avoid

starting a fire. Start with a 60-grit belt; finish with a 120-

grit belt. I round the short point side to glide with a

smooth motion when planing and to easily rotate and

pivot the tool when rolling beads.

Grind the tool’s profile on a 36- or 46-grit wheel (see

“The Modified Profile,” and Photo 2, right). I use a

coarse wheel because this step removes a lot of material.

Sharpen the edge

Switch to a 60- or 80-grit wheel. Adjust the tool rest to

grind the same angle as on a conventional skew.

I prefer to set this angle by measuring distances.

The length of the bevel should be approximately

1-1/2 times the tool’s thickness. The angle between both

bevels will then be 35 to 40 degrees. As you grind, you’ll

probably have to tweak the tool rest’s angle to

get it right.

Two Tools in One

With both straight and curved sections, a modified skew is

quite versatile.

The curved area is great for these tasks:

– Planing and rolling cuts. If you lead with the short point

side and cut with the tool’s curved section, you cannot dig

in. Digging in is a real problem with a conventional skew

and a bane to all novice turners.

– Planing chip-prone woods, such as red oak or figured maple.

– Forming the concave and convex sections of a spindle.

The straight section is great for these tasks:

– Peeling away wood, like a large parting tool.

– Slicing rounded pommels (with the long point down).

– Scraping end grain and knots.

– Working in tight areas. The curve creates a small clearance.

Begin sharpening the straight section (Photo 3). Flip

the tool as you go to remove the same amount of material

from each side (Photo 4).

Now for the curved section. You’ll grind and sharpen

this in one long sweeping motion, using your fingers

as a pivot point (Photo 5). Start next to the

straight section, then rotate the long point off of the

wheel. Continue in one fluid motion down to the short

point. Stop when the area around the short point is

square to the wheel (Photo 6). Then, without changing

your hand position, rotate the tool in the opposite

direction, back toward the straight section. The idea is

to fan the tool back and forth without lifting it from the

tool rest. Make three or four passes on one side of the

tool. Then flip the tool and make an equal number of

passes on the other side. Continue sharpening and flipping

until the bevels meet at the cutting edge.

As with any turning tool, you’ll know when to stop

sharpening by watching the sparks. When they fly off

evenly both above and below the bevel, the cutting edge

is sharp. To confirm that it’s sharp, lift the tool and look

down at the edge under a bright light. A dull area

reflects light; a sharp edge disappears into a black line.

Hone and test the edge

I’m a big believer in honing. An extra-sharp skew is

safer and performs better. I use a diamond slipstone on

high-speed steel tools because it cuts fast (see Sources,

below). To get the angle right, hold the slipstone so it

only rubs on the bevel’s heel (Photo 7). As you move

the slipstone up and down, incline it until it touches

the cutting edge as well; then maintain this two-point

contact. Repeat on the other side. Hone the tool’s sides

near the short and long points, too. Test your tool by

making a light planing cut (Photo 8).

|

|

Click any image to view a larger version.

The Modified Profile.

My skew’s profile has two sections: straight and curved.

The straight section begins at the skew’s long point and

extends one-fourth to one-third of the blade’s width. The

curved section continues to the skew’s short point. The

angle from long point to short point is about 70 degrees,

the same as on a conventional skew.

I also modify my skew’s body. I round over the short

point side and lightly chamfer both edges of the long

point side.

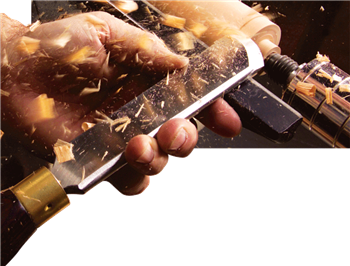

1. Begin modifying

a standard

skew on a belt

sander. Hold the

tool so the belt

always travels

away from you.

Completely round

the short point

side up to the ferrule;

chamfer the

sharp edges of the

long point side.

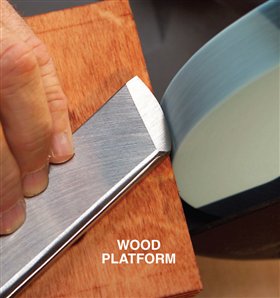

2. Grind the

straight and

curved profiles.

Position the tool

rest about

90 degrees to the

wheel. I’ve mounted

a wood platform

on my tool

rest to have a

broader area of

support, which is

critical for modifying

and resharpening

a skew.

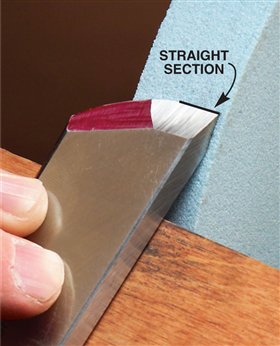

3. Begin grinding

the profile’s

straight section.

Color the

old bevel with a

felt-tip marker to

identify where

the wheel cuts.

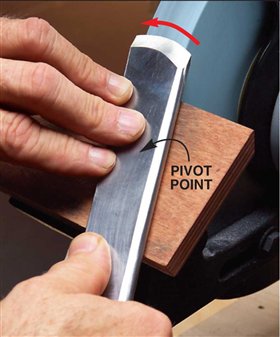

4. Flip the tool

now and then

as you continue

grinding. It’s

important to keep

the bevels on both

sides of the tool

equally long to

center the cutting

edge.

5. Grind the

curved section

by using

your fingers as a

pivot point. Keep

the spot you’re

grinding square

to the wheel.

6. Continue

grinding with

a fanning motion.

When you reach

the short point, as

shown here,

reverse the direction

without lifting

the skew from the

tool rest.

7. Hone the cutting

edge

with a diamond

slipstone. It’s

easy to find the

correct angle by

feel. Hold the

slipstone so it

contacts two

points on the

bevel’s concave

surface: the heel

and the cutting

edge.

8. Check the

tool’s sharpness

by putting it

to work. Make a

planing cut on a

cylinder. A sharp

tool will require little

effort to push,

produce lots of

shavings and

leave a very

smooth surface.

|