We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

I can bend that. With Compwood, you can bend wood in ways that are surprising. When the wood dries, it holds its shape and can be worked with standard woodworking tools.

Video: See Chris bend an arm bow around a form using Compwood.

Article: Read about the drying process and see our makeshift kiln.

Web site: Visit the Fluted Beams web site to order Compwood.

Web site: Read details of how Compwood is made at the factory.

In our store: ”Woodworker’s Guide to Bending Wood.”

Blog: “Compwood Unleashed.”

From the April 2011 issue #189

Buy this issue now

The package of wood looked everything like a mummy when it arrived in our shop. The wood was wrapped in clear plastic, bound by plastic straps and wrapped by more plastic and cardboard.

We peeled away each layer to reveal a stick of unassuming 8/4 ash that was about 6″ wide and 54″ long. Aside from the fact that the wood was cool to the touch, it looked like regular ash.

I took it to the jointer and planer and machined it flat. I ripped off a 1″-wide slice and machined that to 13⁄8” thick, just like any other piece of wood.

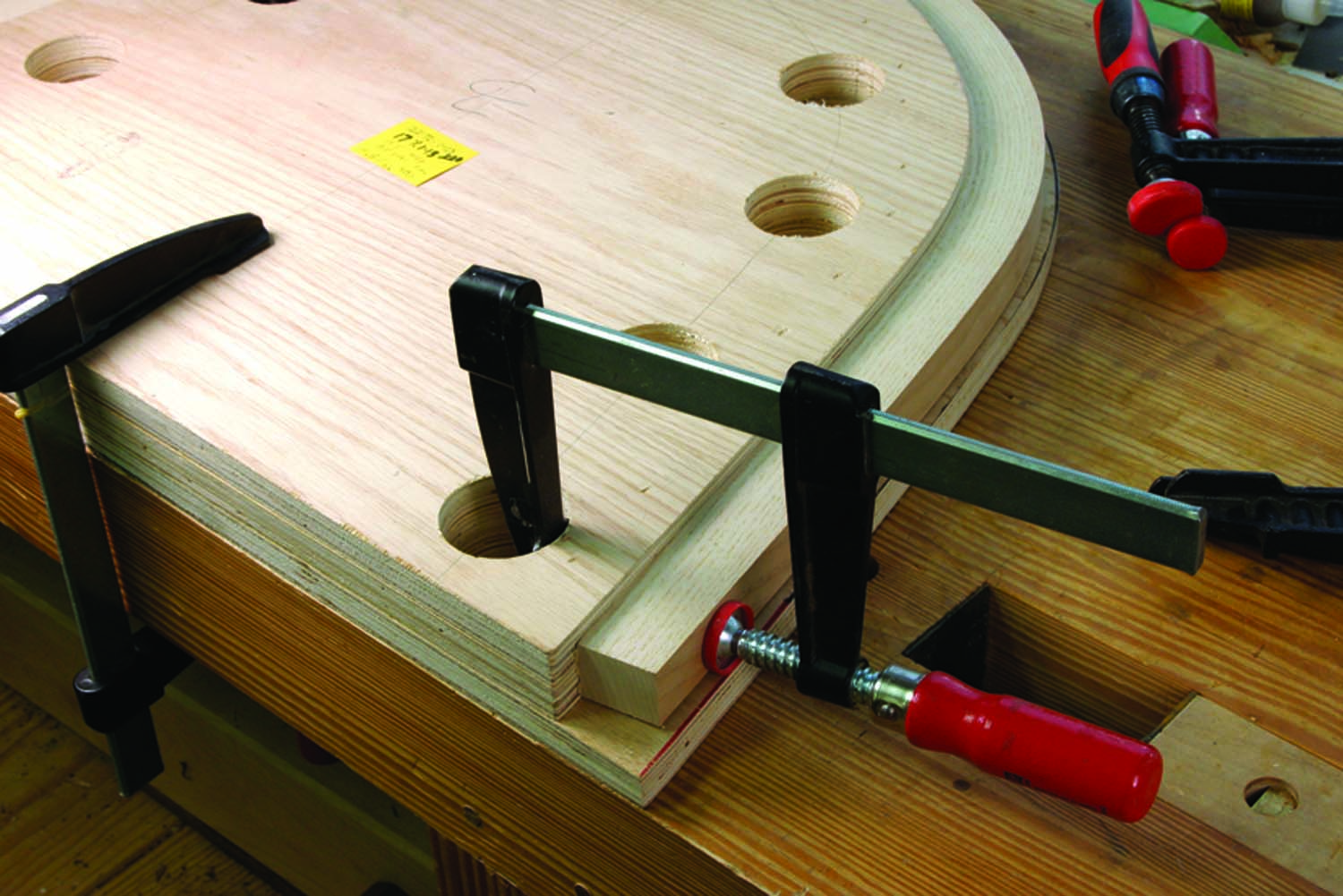

But then I put that stick into a bending form, and the wood gave up its secret identity. Working alone, I bent the piece of ash along its 13⁄8” dimension and pulled it around a C-shaped bending form with a 9″ radius. In 10 minutes, the wood was bent and clamped up. No steam or heat. No adhesives.

This is Compwood, a 1988 European invention that allows you to bend room-temperature wood around a form in multiple dimensions. The lumber comes to your shop wrapped in plastic because it is fairly wet – my piece of ash measured 20 percent moisture content. While it’s wet, you can bend the wood in almost any direction. When it’s dry, it holds its shape and can be worked just like any other piece of wood.

Why Try It?

Flexible terms. Compwood can be bent without steam or – in many cases – a bending strap. It also can be bent in three dimensions.

I became interested in Compwood when I saw it in use at Jeffrey Miller’s woodworking shop in Chicago. He’s been experimenting with the material to use in some of his chair designs and he showed me how it works. Intrigued, I purchased some for my own chairs, and I first cut into this batch to make some arm bows for some Welsh stick chairs.

The Compwood appealed to me for several reasons. While expensive, the Compwood allows me to make my arm bows without investing in a steam box, which I don’t have room for. Also, the material allows me to bend wood to a tight radius without a bending strap and without the risk of compression ruptures on the inside curves or delaminations on the outside curves.

How tight? There’s a formula for each species. For ash, the smallest bending radius without a strap is six times the thickness of the work being bent. So my 13⁄8” arm bow could be bent to an 81⁄4” radius or larger. So a 9″ radius could be bent without a strap.

The Compwood is also less labor- and machine-intensive than a typical cold-lamination job. When I make cold laminations, I typically have to sand all the pieces down to 1⁄8” thick or less for tight bends – that’s a lot of machine work. And I prefer to use plastic resin glue for these parts, and it is nasty and messy stuff.

While I probably wouldn’t consider the Compwood if I made hundreds of chairs for a living (I’d probably invest in a steam box), it did make sense for me for a short run of chairs.

How to Dry it

So how did the material fare? I found that it worked as advertised. After clamping up my arm bows, I let the wood air-dry in the form for a day, and its moisture content dropped to about 12 percent. Then I placed the form in a box that was heated with a lightbulb to 85° F and the work quickly dropped to 7 percent, according to our pinless moisture meter. That’s when I first removed it from the form.

The piece sprang out a little at the ends (though it was nothing unacceptable). The reason for the springback was that the wood likely wasn’t completely dry.

My makeshift “kiln” wasn’t ideal. Miller makes his kilns out of 2″-thick pink foam insulation boards then heats the kiln with a ceramic heater with a fan. His kilns are leaky, which is good because it allows the moisture to escape. He leaves parts in his kiln for about a week. The results were impressive.

“It was pretty much flawless from a springback perspective,” Miller says. “It didn’t move a bit.”

Relax(ed).One of my arm bows sprung out a little after being released from the form before the arm bow was completely dry. Back onto the form for you.

Chris Mroz, who makes and sells Compwood to woodworkers and industry through his company, Fluted Beams, says that I probably removed the wood from the form too soon. For a piece like mine, he would dry it at 110° F for about six days. If he were to air-dry it, he would leave the piece in the form for two or three weeks. So I clamped my arm bows back into the form and let them sit.

How the Stuff is Made

The way Compwood is made is just as interesting as using it. Compwood is made by first steaming the wood at 212° F

until it becomes plasticized. Then it is placed in a press that compresses the wood in length. A 3-meter-long piece of wood will end up about 2.4 meters long when in the press. When the press is released the board will expand again, but it will have lost about 5 percent of its length.

This time in the press bends the cells of the wood like an accordion. The structural change in the cells is what allows the Compwood to bend when it is in a cold but wet state.

Not all species work with this process, but the range is expanding all the time. Fluted Beams, which has the only Compwood press in the Americas, sells 14 different species, from beech, white oak and walnut to cherry, elm and even osage orange.

Softwood species and exotics don’t seem to respond well to the Compwood process, though experiments with exotics are ongoing.

As far as pricing goes, expect to spend $30 to $40 a linear foot for 8/4 material that is about 6″ wide. Thinner stock is considerably less ($18.75 a linear foot). And Fluted Beams (flutedbeams.com or 253-988-2046) also offers small bundles of Compwood for as little as $20 that will allow you to experiment with the wood without buying large planks.

The golden arches. I was well pleased with the way the Compwood behaved for these arm bows. Now I just have to get on with saddling the seats of the chairs.

Mroz quickly acknowledges that because Compwood is expensive it’s not for every job. If the project can be done with steam-bending, that definitely is a cheaper way to go.

“I tend to focus on using this product for things that haven’t been done before – when the wood needs to bend in multiple dimensions,” he says. “It’s whenever the shape gets more sculptural that this product becomes useful.”

And while I can see that side of the equation, I also am a fan of it for my simple bends because it’s easy to use in a small shop with limited equipment. Plus it doesn’t fail spectacularly like some of my steam-bending adventures.

Christopher is the editor of this magazine and secretly wishes at times to be a starving chairmaker, instead of a starving writer.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.