We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

Dovetailed Step Stool

Three kinds of dovetails

make it extra strong.

By Frank Klausz

|

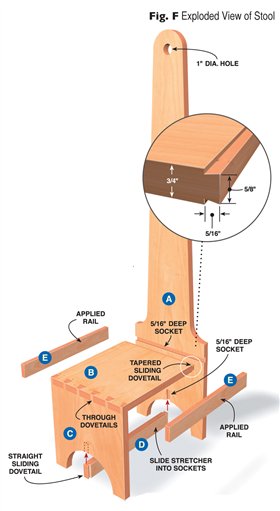

After I finish a large commission, I like to surprise my client during the holidays with a gift—this sturdy kitchen stepping stool. Making one is a pleasure because it’s held together by nothing but dovetails, and I love hand cutting dovetails. A kitchen stool that will face hard use has to be strong. When you stand on the stool and hold onto its tall back for balance, you put extra strain on the joints. That’s why this stool is dovetailed throughout, because dovetails make the strongest connection between wide boards. If they fit tight, the mechanical interlocking alone is enough to hold boards at a rigid right angle. Adding glue is icing on the cake. You’ll need about six board feet of lumber (about $30), to make this stool. The one in these photos is made of cherry, but any wood will do, including pine. You’ll also need some tempered hardboard, 1/4" and 1/2" plywood for the jigs, and a router and router table. After you’ve made the jigs and tried them out, set aside one weekend to make the stool. You’ll find three different kinds of dovetail joints in this stool: a tapered sliding dovetail that goes across the grain, through dovetails, and straight-sliding dovetails that go with the grain.

Preparing the wood

|

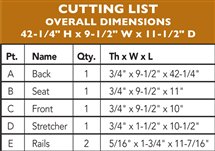

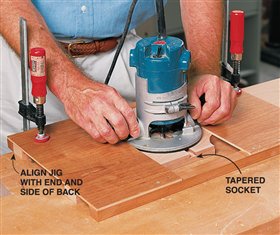

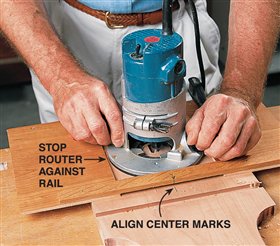

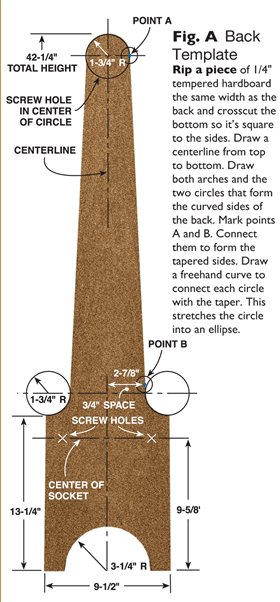

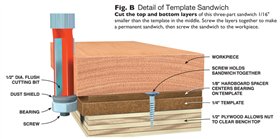

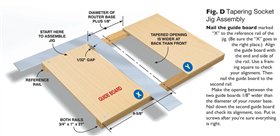

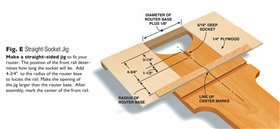

Click any image to view a larger version. 1. Follow a template with a router to shape the back of the stool. The template is the middle layer of a sandwich that allows your router bit to clear 2. Cut a perfect tapered socket with this simple jig. The two pieces of plywood are tapered, so the opening between them is wider at one end than the other. 3. Cut the seat dove-tail on a router table. Shim both sides of the seat to make the same taper as the socket. Adjust the fence by trial 4. Rout the stretcher socket with a second jig. This is a straight sliding dovetail. The jig’s opening has parallel sides. When you bump the router into the top rail, you’ve reached the end of the socket. 5. Mark the length of the stretcher directly from the stool, which is not yet glued together. Cut the stretcher and dovetail the ends on the router table. Fig. A: Back TemplateFig. B: Detail of Template SandwichFig. C: Tablesaw Tapering TechniqueFig. D: Tapering Socket Jig AssemblyFig. E: Straight-Socket JigFig. F: Exploded View of Stool |

4 Tips from Frank Klausz for Dovetailing by Hand

Tip 1. Cut by Eye

|

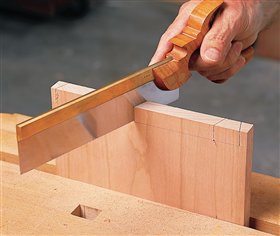

When dovetailing by hand, be bold. Don’t bother with a try square or sliding bevel. After gauging a line across the board, lay out the pins with your saw as you make each cut. Trust your eye to find a pleasing dovetail angle and repeat it over and over. Trust your hands with a sharp saw to cut straight down. If you’ve never done this before, let go of your anxiety and just do it. Practice, practice, practice. You’ll be amazed at how easy it becomes. I’m not worried about the exact sizes of the pins or the spaces between them. In fact, a little variation is a good thing. Your right and left hands aren’t perfectly symmetrical, so it’s okay if your dovetails aren’t, either. |

|

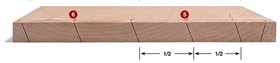

I follow a “rule of halves” when I saw the pins. First I cut the two outer half pins. Next I cut the other side of one tail. |

|

Then I eyeball |

|

I divide the remaining spaces in half again. |

|

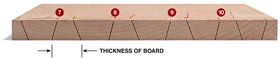

Turning the saw in the other direction, I saw each complete pin. I judge their width by looking at the thickness of the board. |

Tip 2. Chop with Vigor

"I chop out the pins like there’s

no tomorrow. Good, solid blows

on a very sharp chisel get the

job done in no time."

|

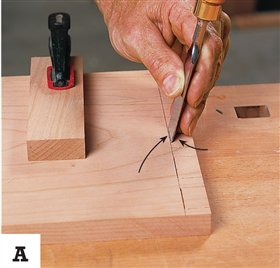

A. To start, I plant the chisel very close to the gauge line, but not exactly on it, and give it a whack with a round-headed mallet. The slope of the chisel’s bevel carries it right into the line. Experience tells me how far to set it away from the line. I march across the board, repeating the same cut. |

|

B. Next comes a sloped cut that defines the shoulder. The chisel is facing the same direction. That’s an economy of movement common to all good handwork. This cut carries the chisel pretty deep, almost up to the first cut. |

|

C. A combination of vertical cuts and sloped cuts remove most of the waste. Actually, I lean the vertical cuts. This “undercutting” saves a lot of time in cleaning up the dovetails. Notice that I leave a flat spot at the end of the waste. If you’ve ever torn out the interior of a hand-chopped dovetail, you’ll appreciate this tip. I chop halfway down one side of the board, brush away the chips and turn the board over. The flat spot supports the waste so there’s no tearout. |

Tip 3. Mistakes Happen! Just Fix 'Em

|

Don’t worry about making a few mistakes. Learn to fix them. Here I had to insert a thin wedge in the joint to make up for a mistake in cutting. While the glue was still wet, I sawed out a couple of wedges and lightly tapped one into an open joint. After the glue dried, I cut the end of the wedge off. |

Tip 4. Level Quickly

|

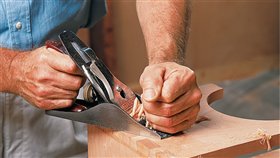

I use a plane to clean up dovetails. When finely set and super sharp a plane slices right across the end grain leaving a smooth, flat surface that you can’t get with sandpaper. I plane from the corners into the middle and take out any ridges the plane may leave with a cabinet scraper. |

|

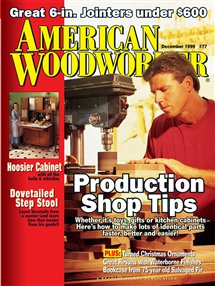

This story originally appeared in American Woodworker December 1999, issue #77. |

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.