We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

Reading

Grain

Direction

“Going against the grain” is a familiar phrase. It means

doing something the wrong way.When you’re talking about

wood, you always want to go with the grain—cutting or

planing a board in a way that follows the natural structure of

the tree (Photo 1). The result is a smooth surface.

How do you figure out which way the grain goes? Some

folks use the coin-toss method.They’ll joint or plane one side

in an arbitrary direction and observe the results.After all,

you’ve got a 50-50 chance of being right! When you’re

wrong,however,you can be really wrong (Photo 2)

and you’ll get tear-out.Whether it’s shallow

or deep, tear-out means extra work

in planing, scraping or

sanding a board.

Tear-out will rarely be a problem for you after we

show you how to read the fibers inside a board.Most

woodworkers think that the ovals or lines on the

surface of a board are the key to grain direction,

but this type of “grain” is not completely

reliable for predicting fiber direction (Photo

3, page 84). Going with the grain really

means going with the fibers. In the

pages to follow,we’ll show you other

clues that are more dependable in

predicting the fiber direction

in hardwoods.

|

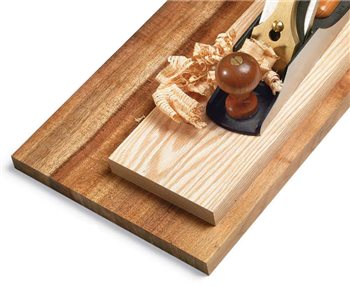

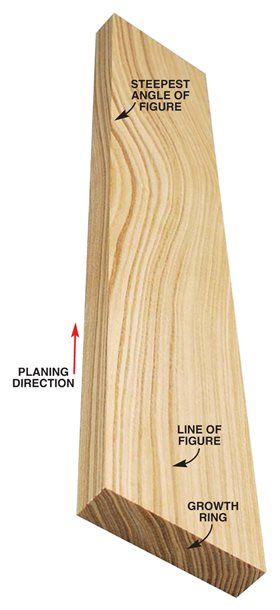

1. Wood is

composed of

long fibers that typically

run at an angle to the surface

of a board. Splitting a board reveals the

direction of the fibers, but we’ll show you

less destructive methods of reading grain

direction on the following pages.

|

|

Click any image to view a larger version.

|

|

2. Nasty

tear-out

is often the result of

planing a board against

the grain.The better you

get at reading grain direction,

the less time you’ll spend

sanding out a mess like this.

|

|

|

|

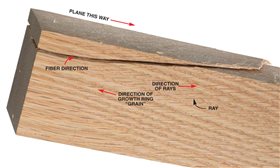

3. Grain direction

can fool you. Normally

we call patterns of

ovals and lines made by

the growth rings the

“grain” of the wood.We

assume that the fiber

direction runs the same

way.The split-off piece of

red oak at right shows

that this “grain” and the

fiber direction don’t necessarily

go the same way.

Small cells called rays are

the true indicators of fiber

direction in plainsawn oak.

(Plainsawn boards are also

commonly called flatsawn

boards. See below for

more information on rays

and plainsawn boards.)

|

|

|

|

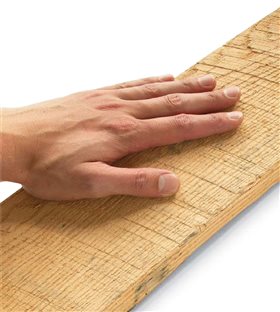

4. Feel the fuzz

on rough lumber.

No kidding, you can tell

which way to plane rough

lumber merely by running

your hand over it! The direction

that the fibers go feels smooth,

while the opposite direction feels

rough and jagged.That’s because many

individual fibers actually stick out above the

surface of rough lumber.You’re feeling their

sharp ends.

|

|

|

|

5. Know where to look. On smooth lumber,

the clues to fiber direction are on the surface

of the wood.

You can’t read fiber direction just by looking at

the surface you want to plane, however.

The clues to look for are on the edge

adjacent to the surface you’ll

plane. To plane the top (1),

look at the side (2). To

plane the side,

look at the

top.

|

|

|

|

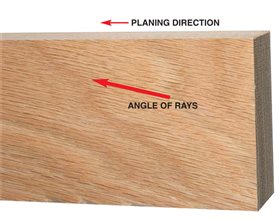

6. Rays are the best clues

to fiber direction in

hardwoods. The general angle

of the rays on the plainsawn face

of a board invariably point in the

same direction as the wood’s

fibers.This typical piece of red

oak is easy to read because oak’s

rays are quite prominent. Beech

and sycamore also have large

rays. Cherry, maple and many

other woods have rays that are

paler and much smaller, but you

can find them if you look closely.

Some hardwoods, such as ash

and walnut, have rays that are

too small to see.

|

|

|

|

7. Look for vessels to

indicate fiber direction

when you can’t see rays.Vessels

are cells that look like

long, dark dashes.They’re

easy to spot on this piece of

walnut once you know what

you’re looking for. Mahogany,

butternut and birch also have

clearly visible vessel cells, as

do many other woods.

|

|

|

|

8. Figure is a last resort.

If you can’t see rays or

vessels, go with the angle of the

dark lines that most woodworkers

call the “grain” of a

board. (“Figure” is the more

accurate term.) We’re all familiar

with the concentric growth

rings on the end of a board

(Photo 9). If you follow those

rings around to the face or

edge, they become the lines

and ovals that lend each board

a distinctive figure.

|

|

|

|

9. Fiber

direction can

often run two ways. Tearout

may be inevitable no matter

which way you plane this board, but

you can minimize it using the clues to

fiber direction given here. In this

piece of ash, the figure made by the

growth rings is the only obvious clue

to follow.The angle of this figure is

steeper at one end of the board than

the other.Always use the steeper end

to decide which way to plane.

|

|

|

|

10. Mark fiber direction on the end of the

board.This mark means “begin planing the

top surface here.” It can’t be accidentally removed

as you mill the faces or edges of your lumber.

|

|

|

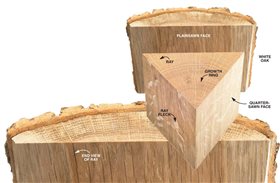

What are Rays?

Ray cells radiate from the center of a tree.These

long, thin ribbons show different faces depending on how

the board is cut from the tree.

You can clearly see the wide side of the rays when the

surface of a board runs at a right angle to the growth

rings.This surface is called a quartersawn or radial face,

and the ray’s wide sides are called ray fleck.

When the surface of a board runs more or less parallel

to the growth rings, you only see the narrow ends of the

rays.This is how most boards are sawn, and this surface

is called a plainsawn, flatsawn or tangential face.

|

|

|

Product Recommendations

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.