We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

Hone your hand skills with a project that has low risks but high rewards.

Trying something new in the shop can be, well, trying. Once I get comfortable with one technique to make a joint, I am loathe to try another, no matter how many people (or magazines) tell me how much better it is.

This is human nature, I suppose. Whenever I want to attempt something new, I try to use it in a project that doesn’t consume a lot of wood or time. That way, if I botch the project, I’ve made just a few sticks of firewood.

This Shaker silverware tray is an ideal project for this sort of experiment. Beginning dovetailers will find this project a good starter project. Want to try using rasps and files? The curves on the end pieces and the cutout handles are excellent practice. How about cutting rabbets or grooves with hand tools? Or even just hand-planing all the boards and giving your sander a rest? This article and its drawings explain how the box goes together; the methods you choose to execute those joints are up to you.

About the Box

About the Box

All the parts for this project are 1⁄2“-thick stock. Using thin stock is what makes this project ideal for people who want to hone their dovetail skills. Thin stock is easier to cut true than thick stock. Cut all your parts to size and then cut your dovetails at all four corners.

The bottom of the tray is a single panel that floats in a groove cut into the sides and ends. The groove is 1⁄4” x 1⁄4“. Cut the groove so it is located 5⁄8” up from the bottom edge of your sides and ends. Note that the groove in the two side pieces needs to be stopped or you will be able to see it on the outside of the project. The groove in the end pieces does not need to be stopped as its exit point will be hidden by the tails on your side pieces.

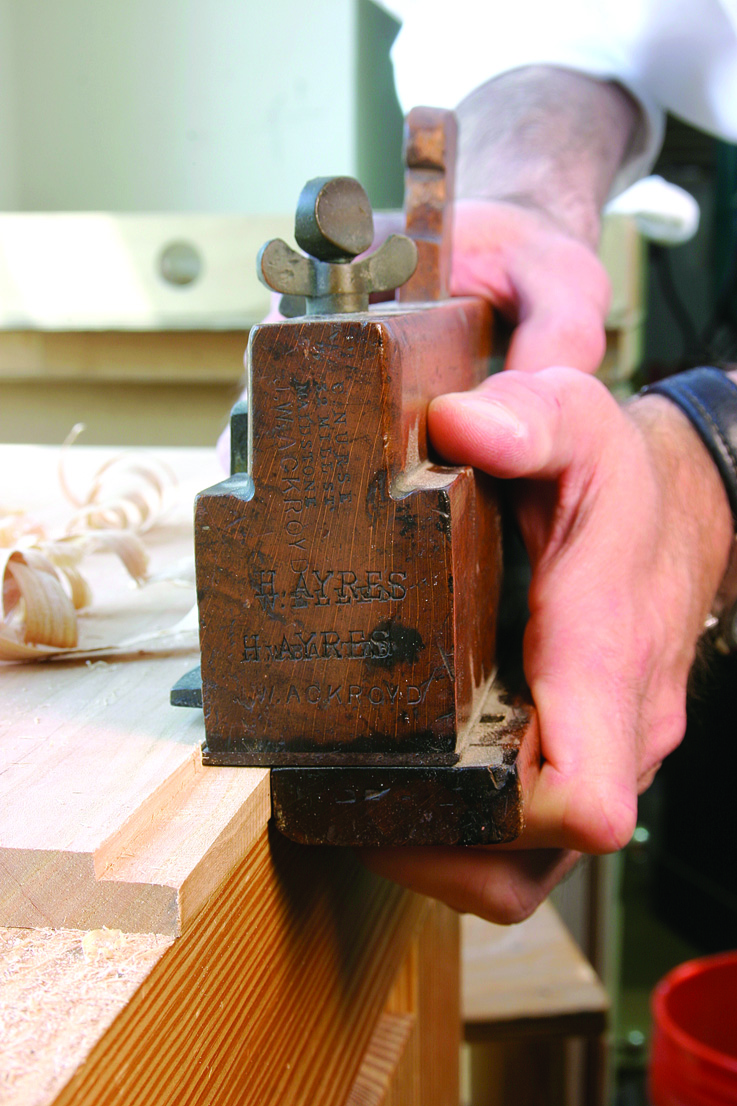

“New” way to make rabbets. A small-scale project such as this is a great way to try out different ways of making joints. Here I’m making the rabbet in the bottom with a moving fillister plane.

The bottom itself needs a tongue on all of its four edges so it will fit into the 1⁄4” x 1⁄4” groove. To create this tongue, cut a 1⁄2“-wide x 1⁄4“-deep rabbet on all four edges of the bottom piece. The rabbet is wider than you need, but the extra width makes it easier to fit the bottom in the groove, and to get the bottom in and out of the groove during both test-fitting and assembly.

The size of the bottom piece is critical. It should bottom out in the groove in the end pieces. But the long edges of the bottom piece should have some room to allow the bottom to expand and contract with the change of seasons. The size of the bottom in the cutting list allows 1⁄16” for expansion on either side.

Cut the curves on the end pieces. The easiest way to mark the curve is to mark a line 11⁄2” in from the top edge of the ends. Take a thin and long piece of scrap and bend it so it joins your two pencil marks on the ends and the top of the end. Trace the curve and cut it.

The cutout handles on the ends are 3⁄4” high, 3″ long and located 5⁄8” from the top edge of the end. Here’s a hint: Use a 3⁄4” auger or Forstner bit to both remove the waste and form the curves on the ends. Then refine and smooth the inside edges of each cutout.

Assemble the box by gluing two end pieces to one side piece. Then slide the bottom into its groove and glue the other side in place. My finish recipe for the box shown here is simple: Rag on a coat of boiled linseed oil (follow the instructions on the container) and allow the oil to fully cure. This takes a couple weeks in a warm room. Then spray on three coats of a clear aerosol lacquer, sanding lightly between each coat with #320-grit paper.

You might be wondering what new technique I tried out when building this project. My new technique was to attempt to build this project for my wife for her January birthday and to actually deliver it on time. And how did I do? Let’s just say it was an excellent Groundhog Day gift.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the October 2007 issue of Popular Woodworking

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.

About the Box

About the Box