We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

Have a vendor mill your patterns on their CNC to start digital woodworking with little effort at low cost.

In earlier posts in this series, I explained how you can take simple computer drawings and make paper patterns. In my last post, I revealed the process I used for years for making MDF patterns. But, how do you do that if you don’t own a CNC? Outsource it. Here are a few tips on finding and working with a local CNC shop.

If you look around your area, you should be able to find a nearby CNC service that can machine patterns for you. When it comes to patterns, I prefer a vendor with a large CNC that uses vacuum hold down. Vacuum holding works better for large sheets of flat material. Smaller CNCs like a 48″ x48″ will work fine, but for this purpose, a larger machine is more efficient. There are a lot of 48” x 96” and larger CNCs in use and a number of small companies might take on simple projects like machining patterns for you.

Possible CNC Services

- CNC service bureaus

- Cabinet Shops

- Sign Makers

- Maker Spaces

- User group members

- Local Furniture Makers

File preparation is important. Layout your patterns to make the best use of your material with little waste. Make sure you leave adequate space between patterns. I find a minimum of 1/2″ works well.

Prepare your Files

If you’re a hobbyist woodworker, persuading a CNC service to output your patterns will likely be somewhat dependent on how easy you make the process for them. As you would expect, every vendor’s requirements will be different. First, contact them to find out exactly how they’d like their files prepared. They will certainly use some kind of CAD or sign making software along with CAM software to program the CNC. Don’t worry, you don’t need to use the same software they using. You just need to provide them with files that their software can read or import. For example: If you’re coming from a drawing program, it’s likely that most services can import “.AI” Adobe Illustrator or “EPS” format or “SVG” files. Almost all CAD software and some drawing software can export “.DXF” format files that are almost universally readable.

Instructions are Important

Once you’ve worked out your CNC service file requirements, you need to give them instructions. Keep them as simple and as clear as possible. I suggest you ask them to cut around the outside of your parts with a .250″ bit. If there are openings in the middle of a pattern or holes to be drilled, make sure they are included in the drawing and let them know that these need to be cut out. Often their CNC programming software will auto detect these openings, but just in case, make sure they are aware of anything to be cut inside a pattern.

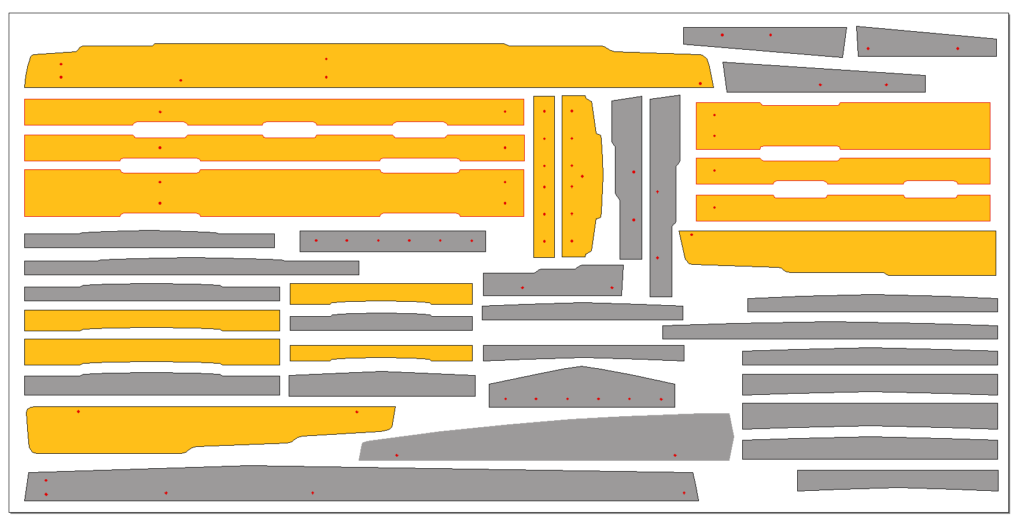

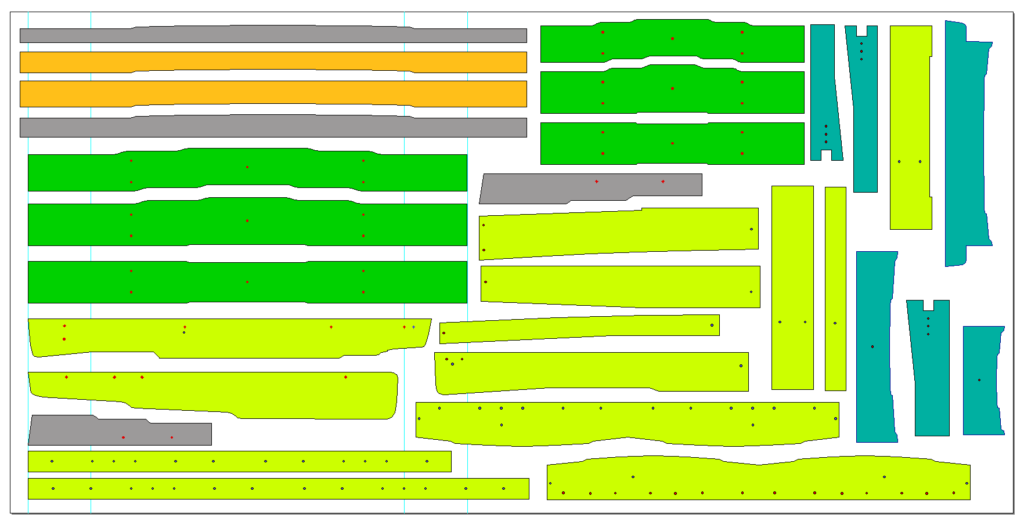

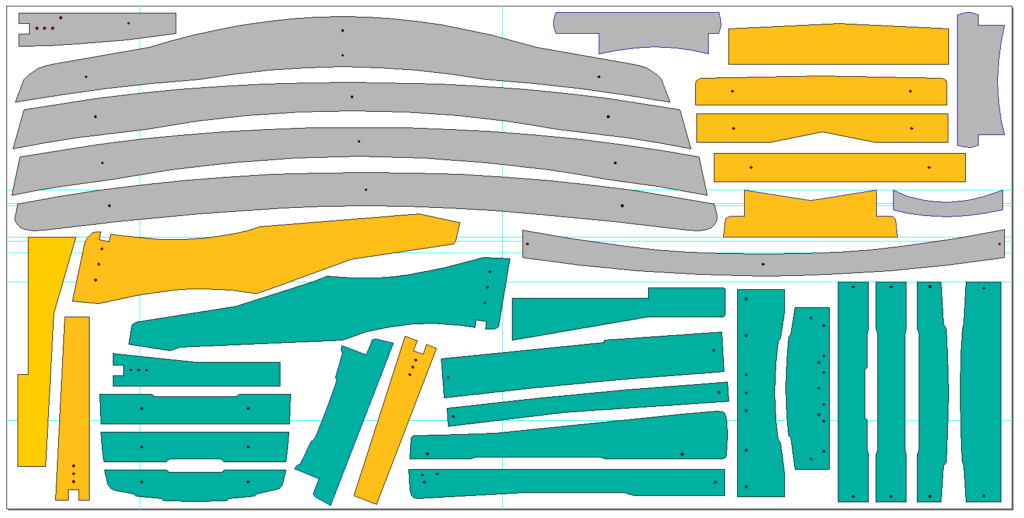

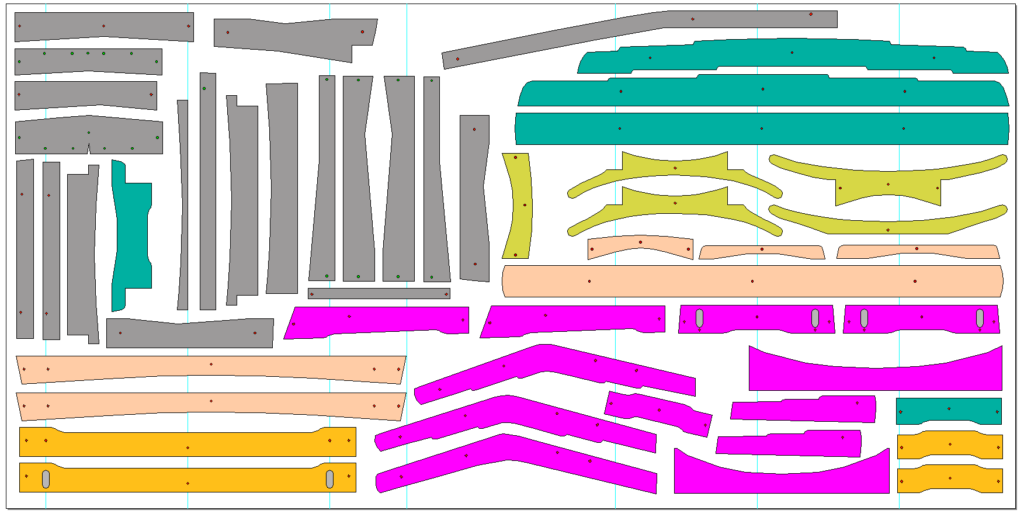

I use color to organize my patterns on a 4′ x 8′ sheet of MDF. Color represents patterns intended for different projects.

Pattern and Jig Materials

Every woodworker has a preference for which material is best for patterns. Some prefer plywood, others MDF or various plastics. Though patterns last longer when they are made out of Baltic Birch plywood, I’ve always used 1/2” MDF. It’s cheap, simple and available. Your mileage may vary, but after nearly two decades, I’ve never worn out one pattern even after shaping several hundred parts on my most used ones. Whatever you decide, check with your CNC service to see if they will supply your material or need you to deliver the material to them for your job.

For other CNC needs — like jig parts, I often use 3/4” MDF and stack layers to the needed thickness. If something needs to be attached for holding— like a clamp that will be held on top of a fixture by screws, I usually turn to Baltic Birch plywood for its additional holding power. On a jig or fixture that will undergo a lot of stress or pressure like a large free-standing bending or lamination pattern, I’ll build up layers of 3/4” cabinet grade or solid core plywood.

Pro tip: Here’s how to stack and align multiple layers — say for a 3” thick jig consisting of four layers of 3/4” plywood. In my drawings, I add .501 alignment holes in the same position for each layer element. Then, during assembly, I use old, extra long .500 drill or mill bits to align the layers while I stack and glue them together. Works great.

Organize your patterns

It pays to plan ahead. I never go to a CNC vendor and ask them to make just one or two patterns. For efficiency, when possible, I try to fill an entire MDF 48” x 96” sheet full of patterns. A half sheet will work, but from a CNC service’s perspective, you’re talking about machine time and setup time. Time is the primary variable that is used to calculate what they will charge you. A half sheet might cost close to that of a full sheet. Ask them for guidance. Efficiency for them usually means lower cost to you.

Once your designs are ready, you need to organize your patterns and lay them out in a way that’s efficient for the CNC vendor and therefore, more economical for you. That means you’ll need to arrange your patterns on a drawing the size of your blank stock. How you distribute them on your stock is a process called nesting. The more you can cram into your blank stock, the more efficient you are with the material and the service’s time. All of the drawings shown in this article show an outside boundary that’s the size of a sheet of MDF. I move my patterns around until they fill up the sheet efficiently.

If you have extra room, try to include as many patterns as you can. This might mean adding in patterns for other projects in order to fill up a full or half sheet. If there’s still space left over, I often include extras, like patterns for smaller projects, sets of butterflies templates for dovetail keys, patterns for half-scale models, custom joinery jigs that I give to students, jig and fixture parts, letters for signage for use at shows. I’ve even included the house numbers for my own home.

Estimating Cost

In my typically heavily populated 4’ x 8’ sheets of 1/2” MDF that is chock full of patterns, I’ve never used more than an hour of machine time for two 1/4” deep passes with a .250” bit. Every CNC service will price their services in their own way, but asking about an hour’s machine time should give you enough information to start a discussion about estimated your costs.

Little details, help. See those tiny red dots? Those are markers for joint, centering alignment and attachment points.

Preparing for CNC Machining

Most CNC service vendors will ask that you leave at least 1” around a sheet of plywood or MDF to allow for clamping and at least at 1/2” between individual parts if your patterns are being cut out with a 1/4” bit. Move patterns round and rotate them to get the best fit. Remember, it doesn’t matter where each pattern is located on the sheet or if they’re lined up. The CNC doesn’t care how you lay it out as long as there’s an adequate gap between parts and extra room around the edges.

As mentioned earlier, I always specify my patterns to be cut with a .250” bit. I do this for a number of reasons. For one, it’s a small enough bit that I can get a reasonable level of detail in tight areas on a design. For another, it allows me to position different patterns fairly close together so I’m efficient with my use of raw materials and a shop’s machine time. Finally, the bit is big enough so that the CNC can move along at a pretty good speed.

My next post will detail some of the tricks that I use when creating my patterns. I’m a bit obsessed with patterns and push them way beyond simple shaping. By the time I’m done tweaking them, my patterns evolve into souped-up story sticks. For example, I use accurately placed holes as guides, alignment markers, precise joinery positons, attachment locations and centerline markers. And much more…

Additional Resources

- All posts on Easy Entry Digital Woodworking, click here.

- Additional Digital Woodworking videos click here.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.

Hi Tim,

You mentioned a few different file formats: i.e.: “.AI”, “EPS”, “SVG”, that will work with most CNC services. I was wondering if “.pdf” files would also work?

Enjoyed your article! Look forward to your answer>

Thanks,

Jim in Edmonds, WA