We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

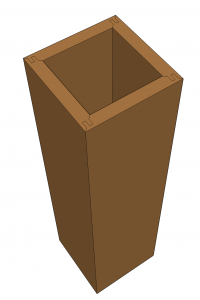

My mattress has been sitting on a cheap metal frame for years. A few months ago, I decided the time had come to build a real bed. With limited tools, I had to come up with a design that could be built without surfacing a bunch of solid stock, so I decided to build bedposts with MDO that I would later veneer with un-backed sapele. MDO is basically veneer-core plywood with MDF on the outside. The plan was to build each post with four pieces of MDO joined with lock miters. I had never made these joints before and knew the router setup would be tedious, but I thought I could make it work.

I spent hours trying to make the posts, but couldn’t get the lock miters right. Every piece I ran through the router ended up with huge blowouts and had to be tossed. I slowed the router down to about 10,000RPM and still got the blowout. I fed the material through as slowly as I could and tried using MDF, which I thought would cut more easily, but I got the same results.

The lock miter bit I purchased for this project didn’t come with any instructions, except for two vague illustrations on the package. Still, I was confident that everything about my setup was correct. My guess was that the 1-1/2-hp router I was using didn’t have enough power. Maybe a 2 or 3hp router could get the job done.

I wasn’t ready to buy a new router, so I had to try again. After some experimentation, I found that putting a little 45-degree chamfer on the MDO with the table saw before routing and setting the router to 10,000 RPMs gave me acceptable results.

Based on the comments I’ve found on several online woodworking forums, most people seem to have trouble setting up the bit height and the fence for lock miters. That was a challenge for me as well, but not nearly as tough as getting a smooth cut that wasn’t missing huge chunks of material.

If you’re going to make lock miter joints, I recommend using a heavy duty router, slowing the bit down as much as possible and removing some of the waste with a table saw before running the material through the router. Trying all of these things together may be the only way you can get good results.

If you’re new to the wood router and would like to learn more, check out Router Fundamentals on Popular Woodworking University. This online course features several hours of video instruction, downloadable plans for router jigs, discussion forums, instructor assistance and more.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.

Oh, and another thing…

Why use such a complicated joint that was just going to get covered? A simple rabbet joint would be just as strong(if not more so), and a lot easier to cut.

I Agree with ‘drsmith’. I was reading the article and was thinking, throughout the article, that he needed to take lighter passes. Sneak up on that puppy and you’ll get better results.

The problem isn’t the size of your router or the speed of the bit. The problem, as you kinda hinted at, is that you’re trying to make the cut in a single pass. That takes out a huge amount of material at once, which invariably leads to difficulty.

Think of it the same way you would when chopping out a dovetail with a chisel. You’ll start by taking out about half of the material (table saw?), then you’ll sneak up to your final cut in successive passes. Once you do that, you should be successful.

Unfortunately, because of the way this was distributed to readers, my comment is pretty much buried in the internet where no one will see it. There wasn’t a link to this page in the email that was sent out, so no one will likely read this comment.