We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

My four-decade-long desire to identify, understand, replicate and develop new analogs to historic furniture-making materials has led me on some interesting quests and situations. Included in these would be learning a lot about tropical insects whose “sweat” is the foundation for the most amazing finish ever (shellac); studies of sausage casings, artificial skin and corneas as I tried to (successfully) create a convincing alternative to tortoiseshell for my own Boulle-work marquetry (including a genuinely surreal episode of waking during eye surgery as they were sewing on my new cornea and attempting to engage everyone in a conversation about protein polymers; “O-h-h-h-h, Mr. Williams, you just have to be quiet right now!”); and most recently into the world of bees, honey, and beeswax.

Why?

Well, it has become increasingly clear to me that beeswax finishing in olden times was not simply a maintenance product, or a second-rate appliqué for furniture, but was rather the primary finish for some of the finest furniture ever made! Historical documents and contemporary scientific analyses confirm that beeswax finishes were the original “French polish” for the exquisite marquetry of the 17th and 18th centuries, and was perhaps the most common transparent finish in early Colonial America.

My initial efforts at using wax for fine finishing have been very satisfying and I will spend the coming days, weeks and years developing a skilled facility in executing it. The historic descriptions of both the material, its processing and, ultimately, its use on furniture is not fully satisfying, so I am using what I know to embark on a whole new journey.

Wanting to control and understand the process fully, I went back to the basics of raw beeswax and started working my way forward. While I have not yet encountered the definitive 17th-century treatise on French beekeeping and beeswax processing, using a technological/conceptual vocabulary that fits that time and place I have begun processing my own beeswax for continued work in this area. I am nowhere close to being done, but the results this far are heartening.

I start with absolutely raw beeswax reclaimed from the honey retrieval process. Little has been done to it before it is sent to me beyond gathering it into blocks.

One of the first things you notice on examining raw beeswax is to think, “Hmm, this is really dirty, what with the multitude of bee carcasses and all.” What you realize when you pick it up is that it is really sticky from residual honey and propolis, the on-board mortar that bees use to assemble their hives. Getting rid of these adulterants is step one for obtaining my own pure beeswax.

One of the first things you notice on examining raw beeswax is to think, “Hmm, this is really dirty, what with the multitude of bee carcasses and all.” What you realize when you pick it up is that it is really sticky from residual honey and propolis, the on-board mortar that bees use to assemble their hives. Getting rid of these adulterants is step one for obtaining my own pure beeswax.

I begin by breaking up the blocks of the dirty, sticky wax into “crock pot sized” pieces which I then stick into the crock pot (instead of the historically accurate wood-ember-heated double boiler). I add about 1 part of water to 2 parts of beeswax and start cooking. When the crock pot gets hot enough to melt the wax, I stir it a few seconds to make sure the sticky, water soluble contaminants become, well, dissolved in the water.

Taking a disposable aluminum casserole pan and a pasta screen, I pour the entire molten mass through the screen and into the casserole pan. The screen captures the large bug parts and the small parts and dirt settle to the bottom.

As the wax cools and hardens, it forms a solid block on top of the water. I flex the pan to retrieve it, and discard the water, which is usually pretty dirty. The bottom surface of the wax block contains a fair bit of debris as well, and I just scrape that off into the trash with a knife.

As the wax cools and hardens, it forms a solid block on top of the water. I flex the pan to retrieve it, and discard the water, which is usually pretty dirty. The bottom surface of the wax block contains a fair bit of debris as well, and I just scrape that off into the trash with a knife.

Using a sledge hammer I break this block of wax into smaller pieces to again place in the crock pot for the second and third cleanings. My setup is to use a large pasta screen as the lower filtering chamber with a smaller pasta filter with a fine screen nestled inside it as the first filter to remove any remaining larger particulates. Inside the larger pasta screen I place a blue shop paper towel to serve as the final particulate filter. It works perfectly at removing virtually all of the particles. (Historically, they would have used either fine fabric or coarse paper.)

When the wax has been run through this gauntlet of cleaning it is a beautiful dark golden nectar that I usually decant into a rubber ingot mold for later use. The advantage of this step is that any remaining wayward specs of dirt will settle to the bottom surface of the ingot and can be spotted and removed with a knife immediately when de-molded.

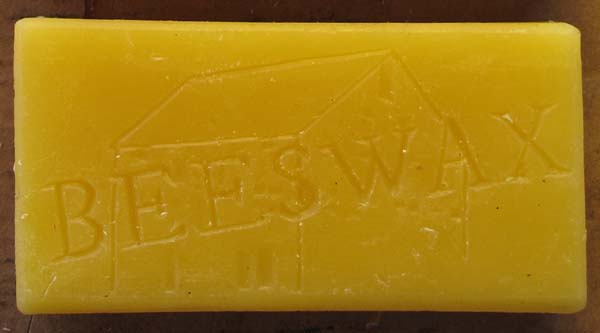

The last step is to remelt the purified ingots, and cast them into their final shape and size (see the picture at the top). I’ve made a number of identical rubber molds to hold slightly more than a quarter pound of perfect wax, the kind of beeswax I want to use in my pursuit of the perfect wax finish.

— Don Williams

p.s. You can read more from Don – on all his many interests – on his web site, donsbarn.com (and drop him a line if purified wax is something you’d like to buy, rather than try processing it yourself…though it does sound like a fun experiment…).

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Now available: The Ultimate Wood Finishing Collection

Now available: The Ultimate Wood Finishing Collection

The ultimate collection for all things finishing! With this exclusive bundle you will not only receive how to information for creating the perfect finishes, but some supplies to get started too! Get expert instruction from Bob Flexner, Don Williams, and Kevin Southwick plus leading supplies from 3M and BT & C, we are bringing together all the best instruction, tools, and all the how-tos you need—finishing your furniture will now be a breeze!

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.

Don – Have you read Coggshall and Morse’s book on beeswax? It’s a good resource though I thought it came up short on the process of cleaning beeswax. If you have any other good resources, please share.

Do you prefer beeswax with more or less propolis? For candles and for lubricating wax, it’s preferred to remove the propolis – but I’m not sure what part it plays in a woodworking finish. I also don’t know that you have much control over it apart from being selective about the wax you start with.

I’ve “refined” quite a bit of raw beeswax, too. I’ll have to try your use of the blue paper shop towels; I’ve always used cheesecloth. I never thought of using the blue towels.

I am surprised that you didn’t mention the part of this project that I find so pleasant: there is something just so wonderful about the smell of a big pot of molten beeswax.

Thank you for researching this and publishing your findings to date. As an organic chemist who lives on 15 acres and has been considering getting a couple of bee hives; the potential making my own furniture wax may have provided the last bit of incentive to take the plunge.