We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

While we lust for a 20″ monster, most woodworkers would be just as well off (or better) with a ‘suitcase planer.’

When I started woodworking in about 1993, I wanted two things: a table saw with a decent rip fence and the biggest thickness planer on the planet.

In my opinion, planers are the biggest labor-saving device ever invented for the workshop. You might think it’s the electric jointer, but I disagree. Any half-witted woodworker can do the work of an electric jointer – e.g. flatten one face and edge of a board – with a $20 jack plane.

But if you want to then remove a 1⁄2” of material from 20 boards and make all the surfaces dead parallel, put your handplane down and fire up the electric planer. It can turn days of sweat into a few minutes of easy work.

For many years, I lusted for an enormous cast iron, induction-motor battleship with a 20″-wide mouth. When I got my wish, however, it was anticlimactic. The finish on the boards it planed was just OK. And I sure as heck wasn’t happy with how much space the 20″ monster hogged in the shop – never mind the bill for the machine or the tedium of the jackscrews when changing knives.

Had I Reached Too Far?

Mouth of the beast. It’s easy to have a strong itch for a massive thickness planer. And if you work in a production shop that deals in wide lumber, you probably should scratch it.

When I set up a new shop in 2011, I skipped the cast iron planer. Instead, I bought an inexpensive, portable, universal-motor planer that fits under a workbench. It leaves a better finish. The knives are a snap to switch out. And I’ve been surprised – no, shocked – by how tough the machine is for daily use.

If you are shopping for a planer, I hope to convince you to save money, space and time by purchasing a portable machine and ignore the call of the heavy-metal sirens.

What’s the Difference?

A different spin. An induction motor can last for 50 years of heavy use and hardly break a sweat. They are bulky and take time to spin up.

At their core, both portable planers and bigger stationary models do the same job and in the same way. Feed rollers pull your wood under a spinning cutterhead. Put rough stock in on one side (note that the face of the board against the machine’s bed needs to be flat); perfectly surfaced boards come out the other side.

Universal motors have instant torque, are small and inexpensive. But they aren’t as reliable.

The difference between the big and small machines is in the details. During my career, I’ve tested and examined hundreds of thickness planers and used them in shops all over the world. Here are my observations.

The Big Boys

A painful change. Traditional jackscrews take time to adjust when changing knives.

The big cast iron planers are powered by induction motors. These motors last forever, are quiet, run at fairly low speeds and are difficult to stall. I have induction motors in my shop that are older than I am. The only real downside to these motors is they are fairly big.

The induction motor in a big planer usually drives the machine’s cutterhead and feed rollers using a robust transmission of chains and gears. These parts are almost always metal and bulletproof, but they require regular lubrication. (If you own a big planer you should know by heart where its grease ports are.)

Carbide inserts are great until you have to change all 300 of them and clean all 300 beds on the cutterhead.

The planer’s cutterhead usually has three knives (or a series of little carbide teeth) that cut the wood. The knives are clamped into the cutterhead using screws or friction. If the cutterhead has carbide knives, these can be changed (laboriously) with a screwdriver. If the cutterhead has three straight knives, they can be changed (super-laboriously) with a variety of tools and a day of downtime.

Adjusting the knives on a basic planer is its own circle of hell. So much so that you end up buying devices with magnets and dial indicators that promise to make it a snap. Truth is, nothing helps more than trial, error and experience to get the knives in position. (Yes, you can buy aftermarket cutterheads with quick-change knives. Why aren’t these standard on every machine?)

The induction motor also drives the planer’s feed rollers, which can be rubber or metal. These pull the wood through the machine. In addition to the feed rollers, many of these big stationary machines have rollers in the bed below that are called (surprise) bed rollers. These rollers help move heavy stock through the machine.

What you also get are a bunch of adjustable bits. You can alter the height of the infeed and outfeed rollers, plus the bed rollers. And you can even adjust the parallelism of the cutterhead to the bed of the planer.

Fiddly bits. The chains, gears and other metal parts make the machine more durable, but also more likely to go out of adjustment in the future.

While these adjustments seem a great idea when you buy the machine, you will quickly tire of them when the machine’s settings slip after vibration and use. Some machines need more love than others, but the bottom line is that if something can go out of adjustment, it eventually will.

After years of pushing thousands of board feet through these machines, I find them to require more maintenance than justifies their capacity in my small shop. But in order to understand why big planers are difficult, you need only go to the home center and pick up a portable model.

Portable Planers

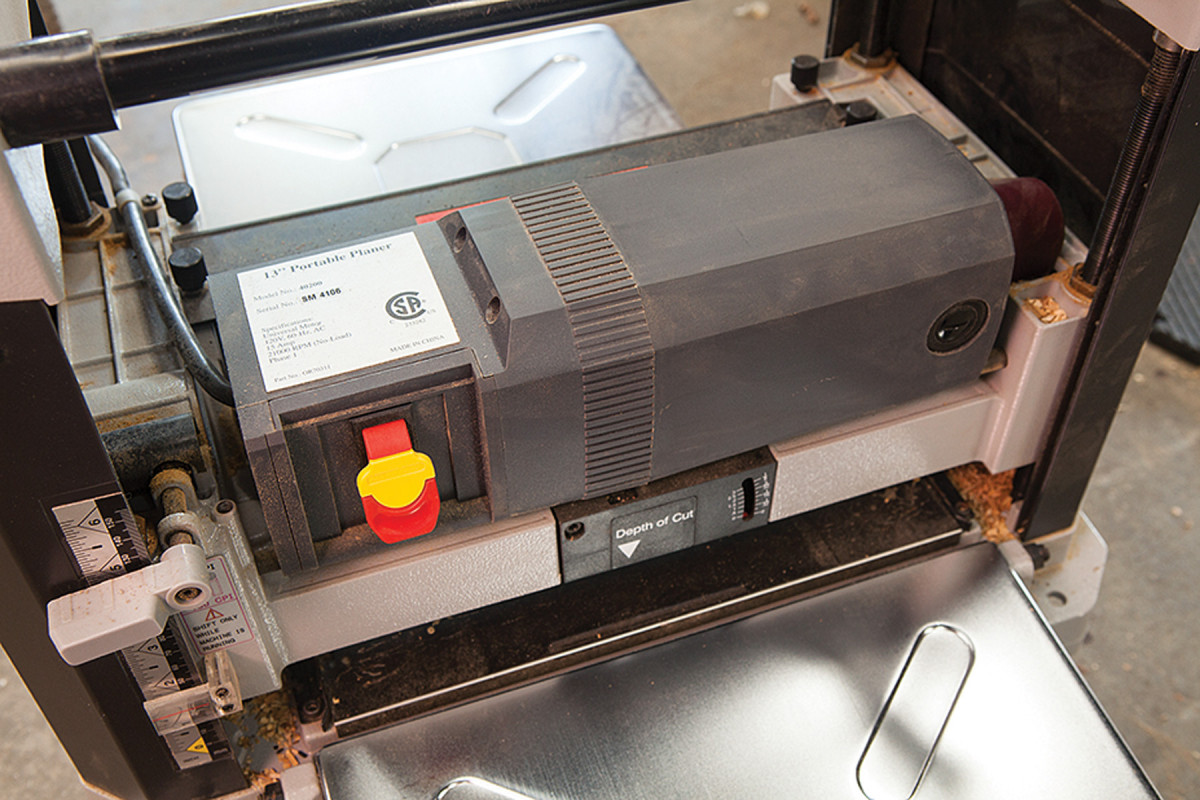

Look for it. A port such as this indicates the brushes of the motor will be easy to replace. Pick up the phone right now and order replacement brushes for your planer. They are good to have on hand.

Sometimes called a “suitcase planer,” this small machine was invented by Ryobi in 1985 and single-handedly changed the market. The inexpensive AP10 10″-capacity machine is still at work in shops 30 years later, and it spawned hundreds of imitators. And many of the imitators became so fantastic that I lost my lust for a cast iron machine.

What’s to love about this machine that looks like an oversized toaster oven? Plenty.

The greatest weakness of the machine – the high-speed universal motor – is also one of its strengths. Universal motors – the noisy beasts in your router, sander and portable table saw – run fast, are small and are inexpensive to make to a high standard of quality.

The downside is they can be stalled more easily than an equivalent induction motor and aren’t as durable. After years of use, you might have to replace the motor’s brushes to restore it to new. (Some manufacturers make it almost impossible to replace the brushes –what’s that about?)

Presto change-o. Quick-change knife systems get you back to work in less than 30 minutes. Once you try one, you’ll not willingly go back.

The small motor size helps make the machine lightweight. The high speed allows the motor to easily spin the cutterhead really fast – the 20,000-rpm motor will be geared down to spin the cutterhead at 8,500-10,000 rpm or so. Compare that to an induction-motor planer that spins a typical cutterhead to only 5,000 rpm.

Why do we care about rpm? In general, faster cutterheads leave a better finish. With a fast cutterhead, each knife takes a smaller bite, reducing the chance of tear-out.

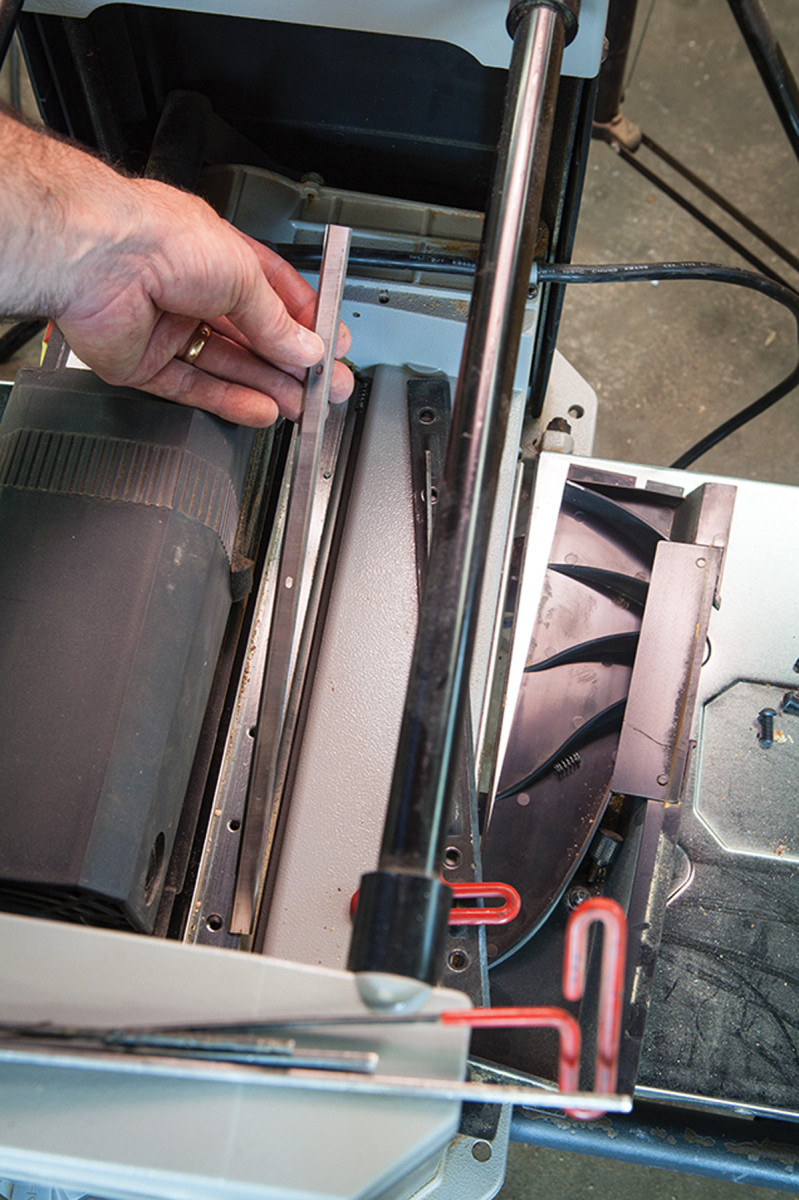

There’s more to say about the cutterhead. Even if portable machines didn’t leave a better finish, I’d still prefer them because – on the whole – the knives are easier to change.

The vast majority of portable planers have a “quick-change” system of swapping out the knives. You usually loosen some screws, remove a plate, then pull the old knives. Then you drop the new knives on some pins on the cutterhead and screw things down. I can change the knives on a typical portable planer in 30 minutes, and they will be set perfectly at that point.

On a typical old-school planer, it can take a couple hours to swap the knives – and then you have to get them all cutting in the same perfect arc. That takes more time and luck. But, you might be saying, what about the spiral carbide cutterheads on big planers? Aren’t those easy to change? Yes, they are simple, but they are even more time-consuming. A 20″ planer can take an entire day. Been there.

You don’t need it. Little niceties such as this stock-removal gauge are almost worthless. Don’t buy a machine based on these little gizmos. Go for simple and reliable.

The advantage of quick-change knives is that you will change them as soon as they get dull and your work will benefit. With the old-school planers, most people put off the maintenance until it absolutely has to be done. By then, a lot of wood has been mangled.

After the cutterhead, the next advantage of the portable machines is their size. Space is at a premium in my shop, so the portable planer was welcome into my 15′ x 25′ workspace. In fact, I saved so much space by getting rid of my cast iron planer that I was able to make space for a second workbench and midi lathe.

Next big advantage: Cost. A good portable planer sets you back hundreds of dollars – not thousands. That leaves more money for wood, hardware and other tools.

And let’s hear it for the gizmos on portable planers! Or maybe not. Many of these machines are festooned with stupid plastic depth stops, variable speeds and other little screwy doo-dads. Ignore them when choosing a machine. Get the one with the best reputation and the biggest capacity.

Not-so-stupid Portable Planer Tricks

You need an extension cord. Yes, a planer can pull itself along like this for long and heavy stock. Do this outdoors and with a long extension cord. It’s like walking a robotic dog.

While portable planers need little maintenance or setup, here are a few tips on getting the most from your portable planer:

1. To make the most of a less-gutsy motor, skew the stock slightly as you put it into the machine. The skew reduces the effective cutting angle and lessens the load on the machine.

2. Lubricate the planer’s bed with a dry lube to make the most of the motor. In my experience, the spray-on lubes are better than paraffin. No, the dry lubes won’t interfere with finishing.

3. Don’t throw away used portable planer knives. That is awesome steel. You can use them as-is (even dull) as scrapers. Or anneal them and you can make them into chisels or anything else. Heck, you can even resharpen them.

4. Not necessarily recommended but too cool: For planing heavy and long stock, feed the planer onto the stock and allow the machine to pull itself along. Yes, I’ve done this. Beer was not involved. I got this idea from timber framers.

5. To reduce snipe (yes, all planers snipe), feed the boards one after the other without pause – tricking the machine into thinking it is planing one continuous board. On the last board, lift it slightly as it comes out to reduce snipe.

6. Clean the rollers. The rubberized rollers of portable planers need cleaning or they won’t grip. Use a non-toxic pitch remover such as CMT’s Formula 2050, especially after planing pitchy pine. If you are someone who goes “all out” in maintenance, dust the rubber rollers with talcum powder to keep the rubber supple (a trick from my automobile restoration days).

7. While you should definitely ignore the thickness gauge on the planer as a way to reach your final thickness, don’t ignore the position of the hand wheel that moves the cutterhead up and down. Many manufacturers time the handle on the wheel so that a certain position – say 12 o’clock – represents one of the common finished thicknesses. For example, my portable planer travels in 1⁄32” increments with every turn of the hand wheel. And all the finished thicknesses end with it at 12 o’clock. When my hand wheel is not at 12 o’clock, then I know for sure that I’m not at a perfect .500″, .750″ or .875″. Experiment with your planer and see if this works.

Disadvantages to Little Guys

Poison for portables. Stock that varies in thickness can stall a universal motor or cause it to trip a breaker. If your stock is like this, take passes to reduce the thick parts down before getting aggressive.

One of the disadvantages to these small planers is they can handle boards up to only 13″ wide. For most home woodworkers that is plenty of capacity. If you need 24″-wide capacity every day in the shop you are quite unusual. Sure, I wish my 13″ planer would take 15″-wide boards on occasion, but I get by.

The other disadvantage is the motor can stall if you deal with wood that has been cut by a drunken sawyer. This is a real concern. In the 1990s I could only afford wood from a sawyer who charged $1 a board foot, regardless of species. He cut it and dried it himself.

The glitch was that his boards tended to taper in thickness from one end of the board to the other. So it was easy to overload my portable planer’s motor. Once I switched sawyers (and started buying better stock), I never had the problem again.

I also have to mention noise. Because of the universal motor, portable planers make a racket. I’ve measured planers that make more than 100 dB, and they get louder when they are under load. Planers with induction motors run much quieter, though you still need to wear hearing protection. The difference, for me, is how much hearing protection. With big planers, I can wear earbuds. With my portable, I wear earbuds plus earmuffs.

You also aren’t going to find as many accessories for your portable machine. If you want to ever upgrade to an indexed carbide cutterhead, you might be out of luck with a portable (though these cutterheads are available for some portables, such as the DeWalt 735).

The final disadvantage of portable planers is that – unlike a cast iron planer – you are unlikely to hand the machine down to your grandchildren. These small machines are durable enough for your lifetime, but they are unlikely to survive as long as a cast iron planer. There are simply too many plastic parts inside a portable planer.

How to Decide

If you run a busy professional shop, you probably haven’t even made it to this point in the article. You think you need heavy metal alone to get the job done. But before you put down this magazine, consider this:

I’ve been in professional shops where the owner used portable and stationary planers in tandem. The big machines beavered the work to a close finished size. Then a portable planer set permanently at one thickness would take all the stock for making face frames to a perfect .750″.

This setup left a great finish on the stock and allowed the face-frame material to work perfectly with the other tooling in the shop without any adjustments.

The funny thing was that one of the shop owners had mounted his portable planer (a Ryobi AP10) to the wall for this – so it wasn’t portable anymore.

Anyway, if you’re not in a production shop or you just build custom one-offs, chances are you can be efficient and happy with a portable machine. Bigger is not always better – or smoother.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.