We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

For those of you who think that sanding and abrasive technology is a fairly new thing, I have news.

Sanding is older than handplaning. As Geoffrey Killen points out in “Egyptian Woodworking and Furniture” (Shire, 1994), Egyptians did not use handplanes. Those tools were invented by the Romans or Greeks. Instead, Egyptian woodworkers used an adze to dimension pieces and then finished off the wood with sandstone.

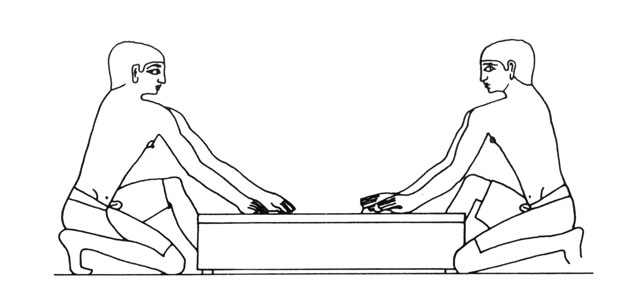

His book shows a wall relief from the Fifth Dynasty (2494 to 2345 BC), from the tomb of Ti in the burial ground of Saqqara. (After Wild, “Le Tombeau de Ti,” Cairo, 1966, plate CLXXIV.) Killen writes:

“They are using sandstone blocks to smooth the grain of the timber, rubbing the block with the grain and not across it, which would have scuffed and damaged the timber surface.”

At this point you might be wondering why am I writing about sanding in an entry tagged “handplanes.”

Abrasive technology, whether sandstone, shagreen (shark or stingray skin), abrasive reed, rush or garnet sandpaper, have all been an important part of the way we smooth wood for thousands of years. Even in the 18th century, which we think of as the height of the handplane-centric universe, sandpaper was carried in significant quantities by Christopher Gabriel & Sons of London (his 1800 inventory listed 11 reams plus six quire of emery paper, and 1 ream of sandpaper; a ream is about 500 sheets). Across the canal, abrasives were also embraced by Andre-Jacob Roubo, the 18th-century French chronicler of the craft.

Seeking a perfect surface right from the smoothing plane is completely possible, even for beginners. But it can be time-consuming, especially with difficult woods. Our woodworking ancestors weren’t nearly as obsessed with shimmering tear-out-free surfaces. Visit any significant antique furniture collection, and when you find original surfaces you will also find small bits of tearing, scalloped surfaces or even some plane tracks from the corners of the tools’ cutters.

To be certain, when joiners and cabinetmakers made pieces for the wealthy or pieces that had to be French polished, the surfaces needed to be immaculate. And those surfaces were usually made perfectly flat by abrasives. And somebody had to foot that significant bill for labor.

So the traditional Western procedure for preparing a piece of wood for finishing goes something like this: plane the surface until it is as smooth and as free of tears as the plane can get it. Follow that with scraping, either with a card scraper or a cabinet scraper. Blend the two surfaces (planed and scraped) with a quick rub of fine sandpaper. If you need a perfectly flat surface for French (shellac) polish, then remove all remaining imperfections with abrasives backed by a firm block.

Oh, and you can stop at any point in this process and call it done. Leave the tree’s bark on the backboards, rough plane the undersides of drawer bottoms, finish plane the interiors of the drawers, scrape and scuff-sand the sides of the carcase, flatten and French polish the chest’s top.

Ah, look. This shimmering surface has a touch of tear-out on one corner. Should I plane the board five more times or move on?

What Does this Mean for Today?

You could read the paragraphs above and conclude that I am telling you to loosen your standards. But that’s not exactly what I’m trying to say. I think it’s important that woodworkers who use planes work at a high level of workmanship, and getting to that high level should be easier the longer you do it.

After almost 25 years of planing wood, I can attest that taming the stuff is not something I ever worry about anymore, even with curly or crotch woods. That’s not because I have better tools; it’s because I’ve seen a lot boards and know how to trick the stuff into doing what I want.

I’m trying to tell you that:

- You don’t have to finish the wood right from the plane. Abrasives are OK, and they don’t change the final appearance of the wood if you use a film finish.

- Little bits of tear-out here and there are OK. Fussing over the surface for hours is not nearly as important as fussing over the form of the piece or the flow of the grain.

- You’ll get better and faster at planing the more you do it. So keep at it.

- Wood is not plastic, so don’t expect it to feel that way. Embrace the different textures your tools can produce. The scallops left by a jack plane are prettier to the eye and touch than an extruded smoothness.

- Finally, don’t judge a piece (or a woodworker) by little bits of tear-out. It’s easy to feel superior when you see a surface imperfection on a piece. Instead, step away from the myopic examination of furniture and evaluate the whole piece: form, function, joinery and then surface quality. The surface finish is the characteristic that is impermanent. It will degrade with use (but I actually think it gets better with age).

So there you have it. Sandpaper and tear-out are OK (in small amounts). Snobbery and fetishism are bad (even in small amounts). The choice, as always, is yours.

— Christopher Schwarz

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.

Really Cool!

This is why I have built mostly shaker, country, craftsman, and as Chris now calls it “furniture of necessity” during my 48 years of woodworking. I’ve never had the time or the patience required to craft a piece with completely perfect surfaces which, to me, is more of an issue with Federal, Chippendale, Victorian, and even modern styles. I’m not an artist so my furniture is never going to be seen in a gallery or museum. My furniture is meant to be used in a house full of life which means it’s going to get banged around and abused. Knowing this, I have always focused more on solid construction, making sure the various elements looked natural together with balanced proportions that are pleasing to the eye. If my client wants flawless surfaces they can buy the particle board stuff put out in mass quantities by the big name furniture manufacturers.

thanks for this wonderful bit of history, Chris. I was wondering if you’ve learned anything about how these abrasive papers were manufactured/how they were constructed. I imagine a relatively thick cloth (like twill, denim, etc), impregnated with gum, and sand stuck on… but maybe not? what kind of cloth/paper, adhesives, and most importantly, abrasives? Were abrasives graded? was it just emery that fractures and gets finer with use (possibly eliminating the need for a multitude of grades..?)?

Well. . .now I won’t feel so un-traditional the next time I pull out my Festool sander to finish a table top.

Yep, your title says it all: “An IMPERFECT Surface.” Perfection by definition: adjective |ˈpərfikt |

1 having all the required or desirable elements, qualities, or characteristics; as good as it is possible to be.

• free from any flaw or defect in condition or quality; faultless.

• precisely accurate; exact: a perfect circle.

• highly suitable for someone or something; exactly right

In my mind, perfection exists in the halls of the gods, it’s a mythical place formed in my heart and my mind’s eye; it is an unreal place that serves as my goal … and I know that because I’m not a god, I’ll never actually get to rest in those halls. In fact, if I “achieve” some perfection, then I must have set my goal too low and therefore the “goal” was imperfect.

As Chris notes, our goal seeking attention is well spent on paying attention to the wood selection and its grain. In fact, we’ll get the best results if we successfully apply our standards evenly and consistently throughout the whole process from first concept sketches to finish wax finish. This holistic approach will help align the holy balance of form versus function versus skill. Don’t forget the design; a “dog” design will remain a “dog” even if it’s well executed and has a perfectly finished top, so we need to spend time designing a pleasing AND constructable piece.

It sounds like a lot of work, and it can be, so this is where Chris’ advice to ease up on perfection comes into play. A benefit of just relaxing on a detail like the finishing is that it allows us to comfortably pay more attention to the earlier stages, including the design (the pen is mightier than the sword, er um saw), and the target wood’s inherent qualities, and how to successfully move that wood into our design and how to move the design into the wood. Relaxing helps us adapt to the wood’s inner qualities that weren’t obvious when it first caught our attention, and oh yeah, relaxing is why many of us do this.

Thank you for that!

Back in the days when naval ships had wooden decks, they were smoothed by “holy stoning.” A sailor with a piece of firebrick would, on his knees, smooth a section of deck and move on. In a later, more modern, era, the bricks were split, lengthwise, a small depression was drilled into one surface and a broomstick was inserted so that the stoning could be done while standing up.