We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

One from many. Here, we see the Stanley No. 55 universal plane and some of the dedicated planes it was purported to replace.

Stanley No. 45 and No. 55 combination planes are put to the test.

“This Universal Tool is a PLOW, DADO, RABBET, FILLETSTER, and MATCH PLANE, a BEADING and CENTER BEADING PLANE, a SASH PLANE and a SLITTING PLANE. It is also a superior MOULDING PLANE and will accommodate cutters of almost any shape and size.

Combining as it does all the so-called ‘Fancy’ Planes, its scope of work is practically unlimited, making the Stanley ‘55’ literally A PLANING MILL WITHIN ITSELF.”

— ‘“55” Plane and How to Use It’

The Stanley Works, New Britian, Conn.

It took 2,000 years of fine-tuning for woodworking planes to reach their peak of subtle perfection – each plane elegantly adapted to its niche in the grain. Then, in a coal-fired flash, they were gone, struck down in top-hat times by the cast iron asteroid of the new machines. Toothed with high-speed rotary cutters, the machines could spit out stock mouldings fast and cheap – and they were good enough. The old wooden warriors that survived took shelter in dank chests as new creatures arose to fill the short-run, on-the-job-site niches where the rotary machines could not (yet) roam.

The creature first emerged in 1884 as the Stanley No. 45 Combination Plane. It was joined in 1897 by the even more versatile and complicated No. 55 Universal Plane. Cast iron and machined itself, the No. 55 was compared by its creators not with the perfection of the earlier planes, but with, as they stated, “a planing mill,” and it too, was good enough.

So what about today? These tools now evoke curiosity if not respect, novelty if not snob appeal. Enough of them survive that one might consider, “Should I get a bunch of planes – or one of these things?”

We’ll test the maker’s claims for these beasts, but first let’s think about planes – not just about how a plane works, but also why a good plane works well.

Set a sharp cutter in a wooden or metal stock, adjust the cutter to take a fine shaving, and you have a plane that works.

But for a plane to work well – in real wood – you need more. The mouth in front of the cutter must be narrow to hold down the wood until the instant before the sharp edge shears and lifts it. The cutter must be fully supported from behind to prevent chatter. The shavings must have a clear escape path to prevent clogging. For clean work across the grain, the cutter must be fitted at a skew angle to make a shearing cut. And, if there are fences and stops, they must to be dead secure against slipping.

The combination planes skimp on all of these attributes. But that does not keep them from serving as…

A Practical Plow

It makes sense that these would work as a plow because the wooden plow plane was father to the combination.

The noble plow, grooving on down the grain, used interchangeable cutting irons to shave grooves of differing widths. These cutters sat centered on a narrow iron skate or runner that substituted for the bed, or sole of the plane. Because the plow just cuts narrow grooves along the grain (such as for panels in doors) any tear-out caused by the open mouth and lack of sole was confined to the hidden bottom of the groove. To keep the plane parallel to the edge of the workpiece, the adjustable fence was held by two wooden arms secured by wedges or by threaded arms locked by wooden nuts. An adjustable depth stop completed this most trusted of the joiner’s tools.

‘Luke – I am your father.’ The wooden plow plane with interchangeable irons and adjustable fences gave birth to the all-metal combination planes. The Stanley No. 45 shown here makes a fine plow plane for cutting grooves – as long as the fence doesn’t slip.

The new iron combination planes took the basic form of the plow plane and added a second runner fitted on two steel rods emerging from the main body. This second runner gave better support on the wood and better backed-up the new, thinner cutters. These cutters could also now link into a cap-nut arrangement to make adjusting the cutting edge exposure easier.

Put on your spurs or drop your nickers! Both mean setting one of the ears of the little three-leafed clover into the down-cutting position and fastening it with the tiny screw. When sharpened and set, the spur will slice the grain just before the cutter engages the cross grain – leaving a sharp shoulder and a clean exit

It’s this easier adjustment that led me to acquire a stable of Stanley No. 45s for students to use as plow planes. The trade-off is employing a plane whose fence won’t hold when placed in the hands of a new user. Too much weight on the left hand will rock the plane out of vertical, generating enough leverage against the fence to force it slightly farther out on the rods. On the second groove of a four-piece frame, they’ll start plowing the groove slightly farther into the stock. On the next, it will be even farther over, and so forth, so that when the frame goes together, the grooves don’t line up. It’s enough to make you want to beat this plow back into a sword!

Still, it’s a good enough plow plane, except for the fence troubles, and because you remove the fence entirely for the next task, the combination planes make…

A Decent Dado

A dado is just a groove across the grain, and to make one you need to kick off the fence and turn down the spurs. Dados are typically too far from the end of a board for the fence to work, so instead, you fasten a batten across the work to serve as a guide for the plane.

Cross grain also needs to be cut, knife-like, before it can be shaved out by the plane. The spurs that did this job on the early No. 55 were retractable knives. Later, we got the little three-leaf clovers held by the tiniest screw you can imagine, and woe to ye that drops one! Although they are a fiddly pain to engage, the spurs on the combination planes work fine once you sharpen them. With the fence removed, the plane can be configured just like a dedicated dado plane, except for one critical factor – the cutter on a combination plane is square across instead of skewed.

Two housings – both alike in dignity. The square-across cutter on the No. 45 at left leaves a far rougher surface than the skewed iron of the dedicated wooden dado plane at the right. You can always get a smoother cut from the No. 45 by setting it to take finer shavings – the job just takes a bit longer.

A proper dado plane has a skewed iron to shear the cross grain with a smooth, clean cut as it feeds the shaving out the side. With the square-across irons on the combination planes, the surface is left rough and the shavings build up and jam. But in the bottom of a dado, most likely to be filled with the end of a shelf, this matters not.

Thus, the square-across iron doesn’t matter because you can’t see it, and the slippy fence doesn’t matter because you don’t use it. Sure, the wing nuts on the right side bump against the batten, and the left-hand depth stop is unreliable, and the shavings get backed up under the frame, but like a dog walking on it’s hind legs, you are cutting a dado with a combination plane! (It is not well done, but you are surprised to find it done at all.)

If removing parts and ignoring rough cutting gets us a serviceable dado plane, I suggest you remove yourself from any visible place before you try the next transformation. Do what you will, but a combination plane makes …

Brain games. If you’d rather play with a Rubik’s Cube than get the job done, then by all means use a combination plane for such elemental tasks as cutting a simple shoulder rabbet. A classic rabbet plane in wood or iron just can’t be beat.

A Ridiculous Rabbet

It hurts to compare the elegance of a traditional rabbet plane to this contraption. You’re pitting perfect form, perfect function, pure elemental beauty against an eight-pound-Edward-Scissorhands-Swiss-army-knife. Using the No. 55 to cut a rabbet is like brushing your teeth with a duck. What if somebody saw you? You would have to pretend were just adjusting the thing to make…

A Funky Fillister

Because a fillister plane is simply a more advanced rabbet plane, you’d expect the combination planes to have all the advances you need – and they almost do.

The old wooden fillister, with a full boxwood bed and skewed iron, leaves a smooth, sheared surface across the grain.

To adjust the width of the cut, mount the fence using the upper pair of holes so it can reach underneath to cover as much of the cutter as you wish. To adjust the depth, dial in the nut on the stop and you’re all set for long-grain work.

But, a proper fillister works for cross-grained rabbets as well, such as the shoulders many folks like to make on the ends of boards that they are about to dovetail. You can engage the spur on a combination plane, but there’s nothing you can do about the square-across cutter. Cross-grained work simply demands a skewed iron to create an acceptable surface.

With the square-across cutter and the two runners instead of a proper bed, the No. 55 travels rough.

But not really. In truth, it works well enough. I lied because it would be tragic if you were to forgo time with a classic moving fillister plane for this nickel-plated lunar lander. Simply behold a good wooden moving fillister plane – the boxwood insert, the stratagems for mounting the spur, the brass of the depth stop. It is a true woodworking tool that makes your work rise to meet it.

There are also metal skew-ironed fillister planes if you prefer, but like the combos, they have rod-mounted fences and…don’t get me started! Too late, I can’t stop, because on the next task, if the fence slips you’ll end up with …

A Mismatch Plane

At its root, we have a decent plane for making grooves, so all we need do is throw in a gap-toothed tonguing cutter and we should be able to make tongued and grooved stock, or match boards as they used to be called.

Tongue in cheek! Combination planes can knock out tongues and grooves – as long as the fence stays put. A dedicated tonguing plane stays set, but can’t be so readily adjusted. In this particular board, the grain turned down in the last 6″, leaving the roughness seen on the shoulder.

But, let us assume that the fence on the plane stays put and see how well this works. Now we are not cutting hidden surfaces in the recesses of grooves and dados. Now we have an exposed edge, and if appearance matters, the grain had better be with you. Sad to say, but the combos have no sole, only that narrow skate; there is nothing to hold the wood down and prevent it from splintering ahead of the cutter. In tongued boards, this rough edge shows.

But no matter; if you do get a rough edge, you can conceal it by simply reconfiguring your combination plane for…

Basic Beading

The No. 45 came with seven beading cutters in various sizes. The No. 55 added two more to these, along with three multiple beads or reeding cutters. With these same cutters, you can make torus beads and return beads, and you can even make dowels by beading in from both sides of a board and then cleaning up the edges. Given good grain, these boys can bead.

Takes a beading & keeps on reeding! In straight-grained wood the combos can bead up a storm. For more accurate work when beading tongued stock, take off the regular fence and put on the little guide seen just to the right of the two runners.

Beads have long been handy to give a shadow line, distract from gaps and make corners tougher by replacing the sharp angles with a rounded surface less prone to splintering and damage. For tongue-and-grooved stock, the “beading gauge” packed with the planes serves as a little auxiliary fence that slips into the socket on the front of the second runner of the plane. Using this fence instead of the normal one ensures that you are fencing against the certain shoulder of the tongue instead of the unreliable tip.

So if the plane can make tongues and rounded surfaces, it’s a small step to put them together to make a…

Surprising Sash Plane

Muntin chops! The sash moulding cutters that come with the combos have screw-adjustable stops in their middles. These stops, along with the adjustable fences, help you create a range of profiles for short runs of window and door stock.

It’s true – you can make the muntins and frame of a glazed window or door with this tool, but it’s in restoration work where it starts to earn its keep. Say you have a damaged window with one small piece missing. You might search out the antique plane that matches – or you can grind a cutter for your combination plane and make the necessary adjustments to replicate that profile. Window work has always demanded the best, straight-grained stock, so let’s take that as a given, and because we’re concerned with only short runs of stock for the repair, we can put up with the other frustrations of the plane.

One thing in the combination plane’s favor is the way the free end of the cutter on the glazing rabbet side allows you to work the moulding in on both faces of a wider board clamped to the bench. Then, you can slice off the muntin with this same plane adapted to it’s minor role as a…

Satisfactory Slitting Plane

Side-slitting entertainment! Fitted with its own depth stop, the slitting knife makes short work of thin stock.

When you’re making slats for shutters or splines for joints, or cutting any thin stock, a slitting plane is a good thing to have. It seems a thoroughly underused tool, but I may be wrong. Because it’s a knife and not a saw, it makes a zero-kerf cut. It leaves no waste and makes no noise, so people may be using them all the time – we’d never know!

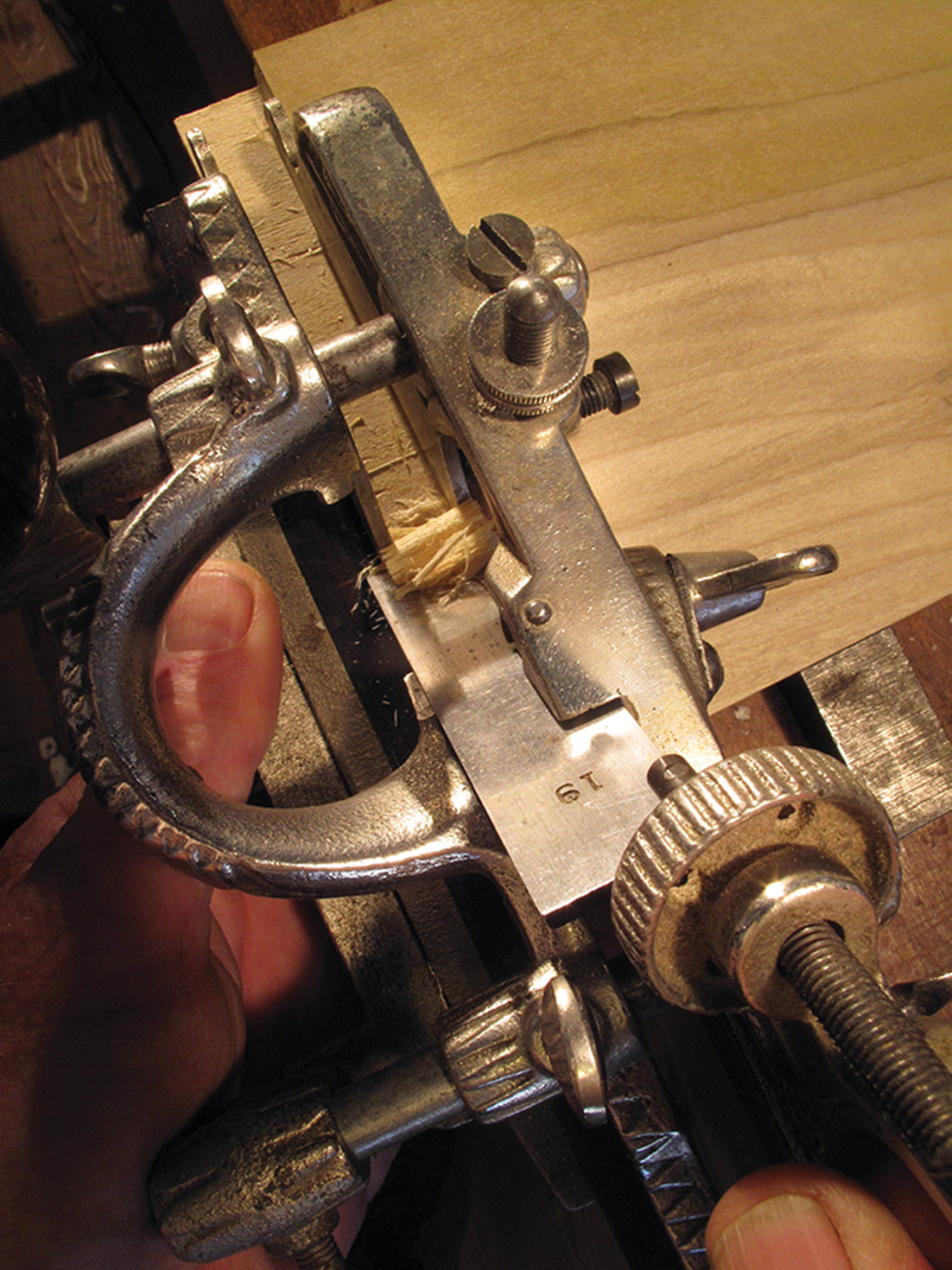

Both the No. 45 and No. 55 came equipped for slitting, and so far we have looked at tasks that both planes could perform. But the prime difference between the two is that the second runner on the No. 55 can be moved not only in and out, but up and down as well, enabling it to serve as …

A Makeshift Moulding Plane

This up and down movement of the second runner gave the No. 55 footing for cutters that reached beyond the flatland of grooves, dados and the level shoulders of the beading cutters. The No. 55 even came with an “Auxiliary Center Bottom,” a third runner that can give more support for wider profiles. But you know the problem; this is a plane without a sole. Such soleless planes need perfect wood to make perfect mouldings. But, if imperfect will do, it works reasonably well, and although it can’t handle diving grain, engaging the spur on the right side of the plane will let it cut a cleaner shoulder than most wooden moulding planes in diagonal or crossed grain.

The No. 55 advantage. Unlike its little brother, the second runner on the No. 55 can adjust up and down as well as in and out. Fitted with the auxiliary runner, the No. 55 can maintain a footing on three levels of the “#105 Grecian Ogee” profile seen here. Along with the supplied moulding cutters, you can shape mouldings from a sequence of contour cuts or grind a cutter to the profile you desire. The process and the product are seldom as satisfactory as with dedicated planes, but sharp cutters and fine adjustment will get the job done.

In fact, it’s respect for old wooden moulding planes that might lead you to acquire a combination plane. A good number of surviving moulding planes have been damaged by tacked-on fences, chiseled-off corners, reground irons – ruinous modifications just to make a few inches of moulding for restoration work. How excellent to have an adjustable alternative that begs to be modified. So any old wooden plane that turns up its wedge at the sight of the No. 55 is both a snob and an ingrate.

No doubt, though, they are ugly things. The No. 55 in particular looks like an alien insect in obscene congress with the wood when fitted with the second tilting fence for…

Occasional Chamfers

The Eagle has landed! The second fence and the rotating rosewood faces on the No. 55 adapt it to chamfer work, but the little spokeshave sitting on the box behind it does a better job. In theory, you can put a beading cutter into the No. 55 at this point and shave a bead into the corner by gradually feeding it deeper and deeper below the runners. In theory, you can empty a lake with a teaspoon.

Yes, indeed, you get two fences with the No. 55 and they both tilt. For working directly into the corner of stock, the left-hand fence holds the plane at the proper angle, the right hand one acts as the depth stop. The left fence moves farther and farther down the sloping face of the work with each pass until the second fence makes contact. Because the cutter makes contact first with the corner of the stock, the runner needs to be precisely positioned to support the edge on that first pass. Otherwise, you are simply digging a heavy knife into the corner of the wood.

Chamfers are intended to be seen, so the tear-out issue is always there. The instructions that come with the No. 55 tell how to solve the problems inherent to chamfer work, but the prospect of two slipping fences leaves me exhausted before I begin – and don’t I have a spokeshave around here somewhere?

So What’s the Verdict?

The No. 55 in particular is an eight-pound solution in search of a problem, but you never know when that problem might turn up. The very things that make these planes so versatile make them prone to error, but keep that in mind and they do fine.

I regularly use a Stanley No. 45 as a plow plane and have adopted a decrepit Stanley No. 55 just to give it a good home. I’m glad to have them. The world is just more interesting with these creatures in it.

Blog: Read more about Stanley Tools.

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in the December 2013 issue of Popular Woodworking Magazine.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.

I tried the link for Watch current seasons of “The Woodwright’s Shop” and got the message of file not found.

Tim