We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

I’m always bemused by woodworkers who boast that they never use sandpaper.

I usually say something to them such as: “Then I guess you don’t like old-school technology.”

When they look confused, I add: “Egyptians used sandstone to abrade wood flat. Sanding is older technology than planing, which is a Greek or Roman invention.”

As far as I know there hasn’t been a definitive history written about abrasives. And please don’t ask me to write it – I have enough to do on this earth already. So if you need a good idea for a gritty bestseller….

The problem with abrasives is how they are abused in this modern day. Abrasives have almost always been some part of the finishing process, but the key word in that sentence is “part.” Today, most modern shops start with abrasives and end with abrasives. And that’s when they become the lung-clogging, vibrating misery known as power sanding.

So let’s take a close look at a more balanced approach that was practiced in England during the 19th and 20th centuries. It’s explained here by Charles H. Hayward in the book “The ABC of Woodwork.”

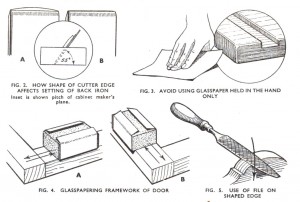

“Cleaning up a panel, table top, or whatever it may be is a fairly straightforward job. The smoothing plane cutter is sharpened to as straight an edge as possible, and the plane is set fine with the back iron as close as possible. It is assumed that the wood is already true and requires only to be skimmed to remove marks or tears made by the trying or panel plane. The entire surface is gone over with the grain. In most woods, the tears will come out, though, admittedly, there are difficult woods. So much depends on the plane and the way it is set. The cabinet maker’s smoothing plane has a high pitch in which the action approaches that of scraping rather than cutting, and if this ha the back iron set fine there are only a few woods which cannot be planed. (Remember on this score that the straighter the edge the more closely the back iron can be set.)

“In any case, however, the scraper must foll ow for all hardwoods. It is not only that it will remove any tears that may be left, but it will take out all marks left by the plane. This is a point that is easily overlooked. Then again, in some difficult woods the grain runs in streaks about 1/4 in. or 1/2 in. wide, and it is impossible to plane one with the grain without tearing up those adjoining. The scraper can be bent and used on a comparatively narrow area of the wood.

“Glasspapering follows, and a flat rubber (usually of cork) is essential. The purpose of glasspapering is only partly to smooth the surface; it has for its second object that of getting rid of marks left by the scraper. This cannot be done when the glasspaper is merely held in the hand. The pressure is uneven and is not great enough. Furthermore, all sharp edges and corners are liable to be dubbed over, giving a dull, unspirited appearance to the work.”

To summarize: Plane until you cannot improve the surface. Scrape until you cannot improve the surface. Sand until you cannot improve the surface. Finish.

This is the way I’ve worked for many years. I buy a box of #220-grit Abranet every couple years, and that covers all my sanding needs.

And one last detail: Hand sanding is a hand process requiring great skill to execute – especially when it comes to contoured surfaces. So don’t hide your sandpaper when your breeches-wearing hand-tool buddies come over for a beer.

— Christopher Schwarz

If you want to learn a lot more about handplanes, check out my book “Handplane Essentials,” a huge tome on handplane work that encompasses much of my writing on these tools for the last decade. Click here for details.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.

Thank you for you permission to sand. I will now dig my random orbit sander out of the hole I buried it in under my garden shed, where I was forced to hide it in fear of persecution. Many nights I lost sleep wondering if and when roaming mobs of hand tool enthusiasts would pull me from my home to re-educate me. I feel safer now.

Hello Christopher. I am writing from Argentina. Workbenches found your book on Amazon, you can buy and sent by post at home in the city of La Plata. My English is not very good, but with google and common sense’m translating your concepts.

I’ll be looking at, according to the types of hardwood and semi hard to comerciarlizan in Argentina for you to recommend the best adatpe to build my workbench

My profession is electrical engineering Extra High Voltage and I work with a lot of enthusiasm to the professional carpentry furniture.

Best Regards

Ricardo Raia

Hola Christopher. Te escribo desde Argentina. Encontré tu libro Workbenches en Amazon, lo puede comprar y lo enviaron por correo postal en casa en la ciudad de La Plata. Mi ingles no es muy bueno, pero con el google y el sentido comun voy traduciendo tus conceptos.

Te estaré consultando , de acuerdo a los tipos de madera dura y semi dura que se comerciarlizan en Argentina para que recomiendes la que mejor se adatpe para contruir mi banco de carpintero

Mi actividad profesional es la ingenieria electrica de Extra alta tension y me dedico con mucho entusiamo a la carpinteria profesional de muebles.

Un cordial saludo

Ricardo Raia

Personally, I use power tools to take the drudgery our of a project. I have begun hand tools more and more when I am building something that I consider important, at least to me. I find my mistakes happen slower with hand tools. It’s not about adherence to using only muscle powered tools even though a lot of those are cool. It’s about learning a type of work that was largely forgotten. I know I will never be fast enough to have worked in an 18th century joiner or cabinetmaker shop, but that really isnt the point. Also, it’s therapeutic. All the stress of modern life drains from me as I work a chair leg with a draw knife. Am doing it ‘correctly’? heck I dont know, but at the end, I have made a chair leg, and enjoyed doing it. And I use both power sanders and sanding blocks, when it seems to make sense.

“Do not follow in the footsteps of the old masters, but seek what they sought.” Basho

I’m coming at this from the perspective of a power tool user who is now using more hand tools. I am seeking the best ways to get the results I want. Often that means using and mastering hand tools.

What a great post. Makes so much sense. Thanks!

As with most woodworking tasks, don’t drink and sand. One other great suggestion is when you do need to sand, use a high quality product and keep using new areas of the paper.

The method described above is how I was taught at school and the method I follow to this day. The process of completing your project is about working with care to minimize any marks you might inadvertently put into your work and moving onto the next process that removes the marks left by the previous process. Use an appropriate finish after sanding to 220 grit and possibly go finer before the final coat of finish.

The problem lies with the 21st century handtool amateurs believing that they must emulate 18th century handtool professionals.

“So don’t hide your sandpaper when your breeches-wearing hand-tool buddies come over for a beer.”

A poke at Mr. Cherubini perhaps?

Charles Hayward was writing for 20th century amateurs, not 18th century professionals.