We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

Choose complementary blades for perfect results.

In the dark ages of woodworking, before carbide, you never used the same blade for ripping and crosscutting. Cutting plywood required yet another blade. Today, hybrid blades allow you to avoid blade changes entirely—unless you want absolutely perfect results. Then it’s better to have more than one blade. I’ll show you how to choose the right primary blade and then which blades would make the best companions.

Start with a 40-tooth General-Purpose Blade

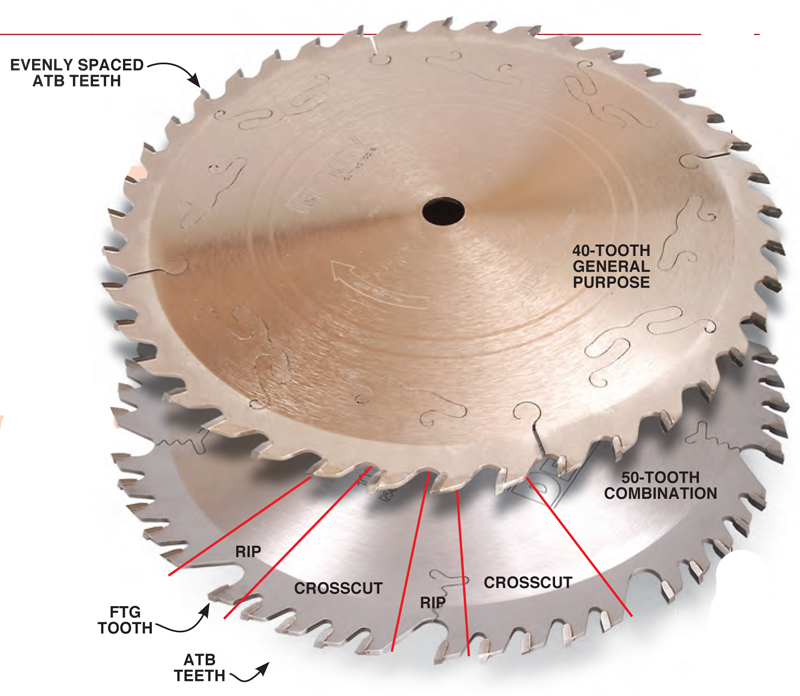

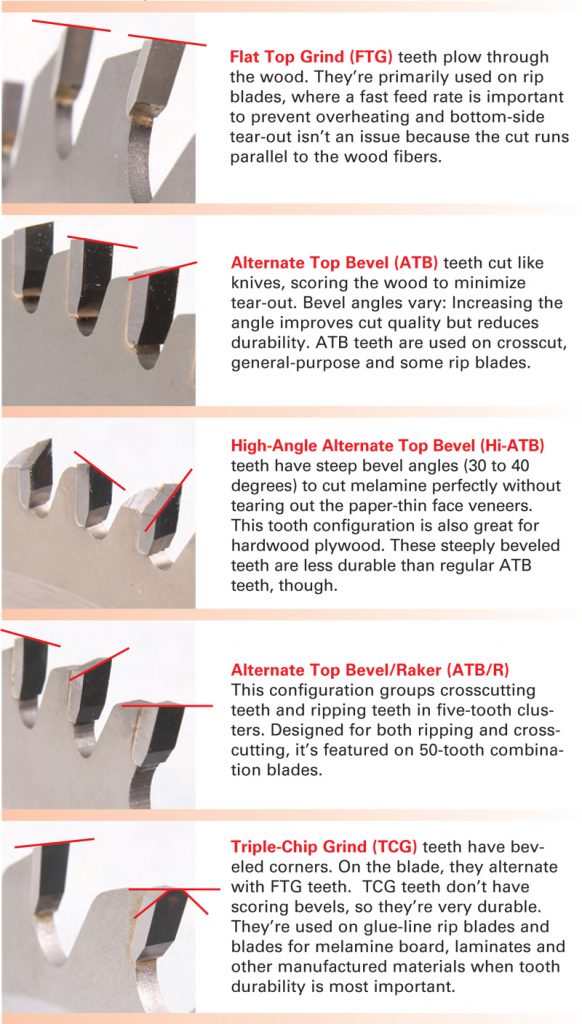

Every workshop needs a primary table saw blade that can satisfactorily make every cut in every material. Two types of blades fit that bill: 50-tooth combination blades and 40-tooth general-purpose blades. Both types are designed to replace separate rip and crosscut blades, which are distinctly different. Rip blades are designed to cut in line with wood fibers. They have large gullets for sawdust removal and 10 to 40 flat-topped, widely spaced teeth that cut aggressively. Crosscut blades are designed to slice across wood fibers without tearing them. They have smaller, more numerous gullets and 60 to 100 alternately beveled, closely mounted teeth that cut cleanly.

The 50-tooth combination blades have two kinds of teeth, some for ripping and some for crosscutting. The teeth on 40-tooth general-purpose blades are adept at both ripping and crosscutting. For a primary blade, I prefer the 40-tooth general-purpose blades. They rip slightly faster than the 50-tooth blades, because they have fewer teeth, and crosscut just as well, because all the teeth are crosscut-friendly. This tooth design also leaves less bottom-side tear-out on hardwood plywood. The 50-tooth combination blades have some minor advantages. They’re often less expensive than 40-tooth blades and they’re better for cutting dadoes and grooves, because the top of the kerf is virtually flat.

Choosing a primary blade isn’t difficult, because the difference in cut quality between good blades is marginal. With so many good general-purpose blades available, your priority should be to avoid economy blades. The sawblade market is extremely competitive, so don’t worry about price gouging. Just choose blades that fit your budget. The general-purpose blades I tried cost $45 to $100. The higher-priced blades performed marginally better, but there wasn’t a stinker in the bunch.

Primary Blade Choices

40-Tooth General Purpose Blade

A 40-tooth general-purpose blade is the best choice for a primary blade and the one blade every woodworker should have. These blades have evenly spaced, alternately beveled (ATB) teeth. Examples: Amana #PR1040, $60; DeWalt #DW7657, $50; Infinity #010-040, $90.

50-Tooth Combination Blade

A 50-tooth combination blade, the original hybrid design, is half rip and half crosscut. These blades have 40 closely spaced, alternately beveled (ATB) teeth, like a crosscut blade, and 10 widely spaced flat-topped (FTG) teeth fronted by large gullets, like a rip blade. These blades are good, but 40-tooth general-purpose blades, a newer hybrid design, are better.

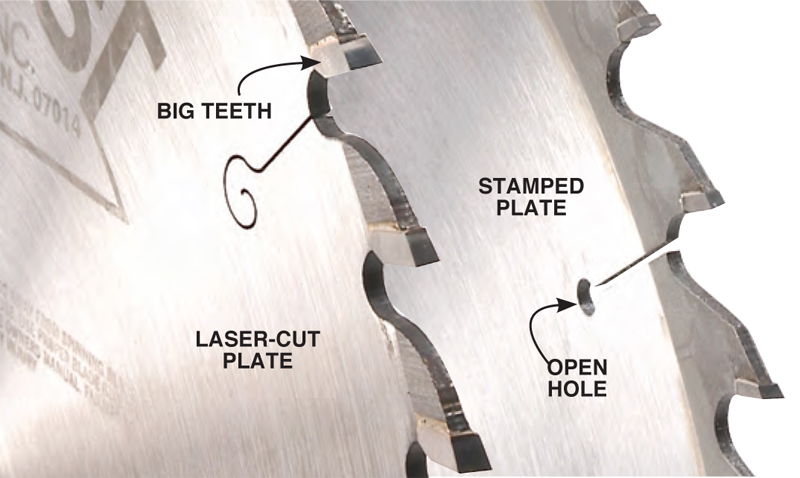

Spot good quality at a glance. The best blades don’t scrimp on carbide or steel. Designed for long life, their teeth can be resharpened many times. Economy blades almost always have thin, stamped steel plates. Expansion slots that end bluntly in open holes signal old technology and a noisy blade.

Blade Anatomy and Must-Have Features

Understanding blade anatomy allows you to quickly identify a blade’s function—and gauge its quality. Function is indicated by tooth count and geometry. Quality starts with two must-have features: A laser-cut plate and teeth made from hard, microscopic grains of carbide. You can’t tell by its appearance whether a blade has these two important features. If they aren’t specified on the blade or its packaging, call the manufacturer and ask.

Laser-cut plates improve blade stability. They’re made from harder steel than old-fashioned stamped plates. Laser-cut plates on top-quality blades are processed further, to remain virtually dead flat and vibration-free during operation. Economy blades often have laser-cut plates, but they may lack any additional stabilizing processes, such as flat-grinding or tensioning. For sharpness and durability, the best teeth are molded from the tiniest particles of the hardest carbide. Look for particle sizes less than 1 micron and for C4-grade hardness.

Tooth Geometry

Tooth geometry includes the top profile, the hook angle and the relief angles. The top profile and angles work together. For example, rip blades have flat teeth, high hook angles and wide relief bevels for fast cutting. Different manufacturers typically use different combinations for the same cutting application. Manufacturers may also offer more than one blade for the same application. One profile/angle combination produces a cleaner cut; another combination is more durable.

Click on an image to see a larger version.

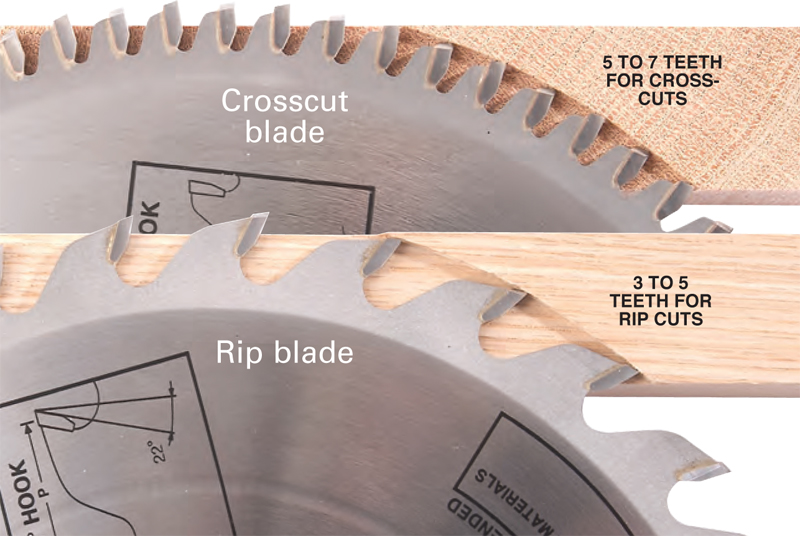

Tooth Count

In general, a blade with more teeth makes a smoother cut but runs hotter. To avoid overheating, three to five teeth should be engaged during a rip cut. For crosscuts and sheet goods, five to seven teeth should do the work. To maintain the correct engaged-tooth ratio, a blade with fewer teeth for cutting thick stock would be ideal. Another solution is to adjust the blade’s height (with the blade guard in place). Raising the blade higher reduces the number of teeth in the cut. It also increases the hook angle, which makes the blade more aggressive, so the cut’s quality decreases.

Additional Features

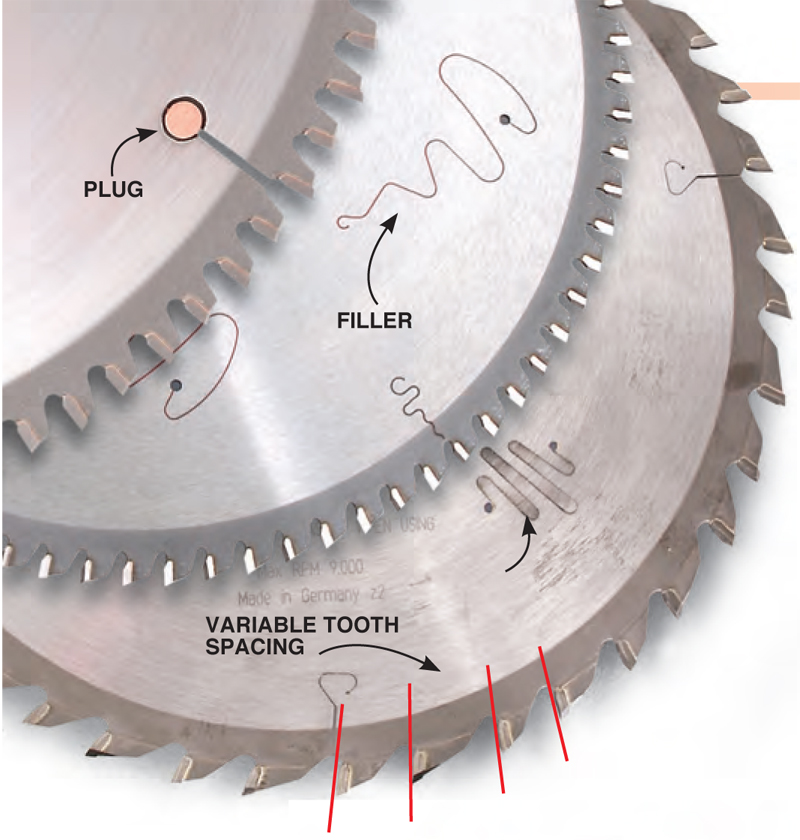

Sound Dampening

Sound-dampened blades are noticeably less noisy. But even with the quietest blade, sawing requires hearing protection. Sound dampening also reduces vibration, so it makes a blade run smoother. Methods include vibration-absorbing fillers and plugs, laser-cut reeds and variable tooth spacing. Using one finger as an arbor, test a blade for effective dampening by snapping the plate. A dull thud is good; a dinner-bell ring is bad.

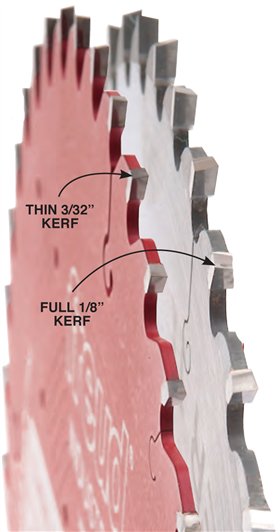

Thin Kerf

Thin-kerf blades are a boon to overworked motors. If your saw frequently bogs down during cuts, switch to a thin-kerf blade. It removes about 25 percent less material, so your motor doesn’t work

as hard.

State-of-the-art thin-kerf blades cut just as well as regular kerf blades, although most manufacturers recommend using stabilizers for optimum performance. Material savings are often touted as another benefit, but they’re negligible: It’ll take 32 cuts to save 1 in. of wood. Examples: Freud #LU86R010, $35; Forrest #WW-10-40-7-100, $90.

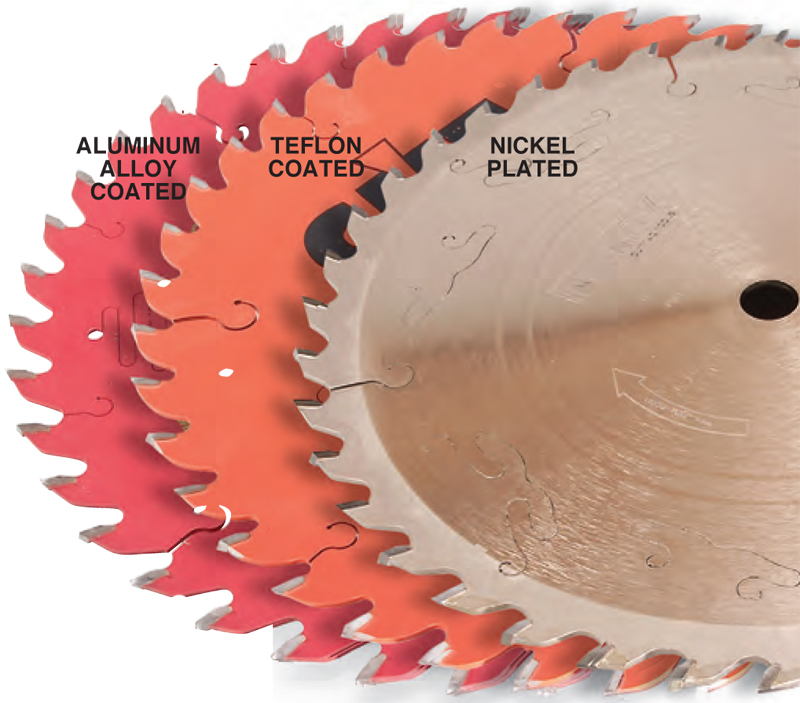

Blade Coatings

Are blade coatings beneficial? The answer varies with who’s talking. Manufacturers who apply coatings claim they help blades run cooler, make them easier to clean and fight corrosion. Manufacturers that don’t apply coatings allow that coatings help with cleaning, but claim they don’t provide other significant benefits.

Recommended Companion Blades

Even though today’s 40-tooth general-purpose blades are durable, relying exclusively on one blade has drawbacks. For example, a critically important crosscut is sure to appear immediately after you’ve ripped miles of 2-in.-thick white oak. For best results, you should have at least two blades, so you can keep one sharp for critical cuts. Instead of buying two identical blades, it makes more sense to choose a good companion for your primary blade.

Even with state-of-the-art technology, a general purpose blade designed to make every cut still won’t make any cut quite as well as a specialized blade. For example, a blade designed to cut hardwood-veneer plywood may reduce tear-out by only 5 percent compared to a state-of-the-art general purpose blade. For demanding users, though, that 5-percent improvement may make all the difference.

If you don’t want to compromise, augmenting your general-purpose blade with one or more companion blades is well worth the cost. The same advances in materials, design and manufacture that produce today’s excellent general purpose blades are used to produce specialty blades. As a result, these blades produce better results than ever at their specific tasks. And by having several blades, you’ll get a longer service life from each one.

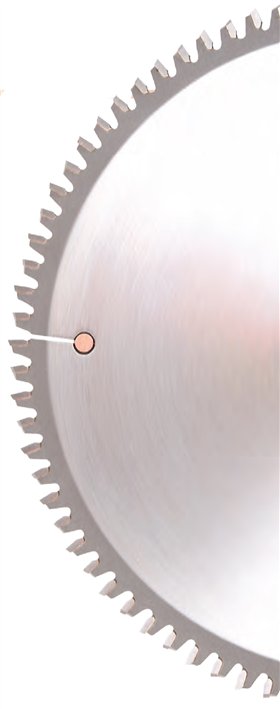

Hi-ATB Blade

Add an 80-tooth Hi-ATB blade if you cut lots of hardwood plywood. Hi-ATB blades leave nearly perfect bottom-side edges on melamine and hardwood plywood. They combine steeply beveled teeth and very low hook angles to virtually eliminate tear-out. You’ll also get great crosscuts in solid wood less than 1 in. thick, which makes this blade an ideal companion for your general-purpose blade—its 40 teeth are well-suited to handling crosscutting chores in thick stock.

Hi-ATB blades are called melamine, trim/finish or fine-crosscut blades. The surefire way to identify them is by their tooth profile. Examples: Freud #LU80R010, $70; Mercer Industries 711202, $56.

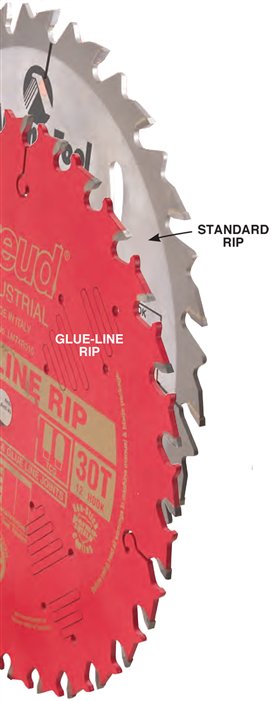

Glue-Line Rip Blade

Add a glue-line rip blade if you rip lots of solid wood. At the cost of a slightly slower feed rate than a standard rip blade, a glue-line rip blade leaves cleaner edges that may not require jointing before gluing. Because of its durable TCG teeth, this blade can also cut abrasive manufactured materials like particleboard, which saves your general-purpose blade for crosscutting solid wood and hardwood plywood.

Glue-line rip blades aren’t designed for cutting stock thicker than 1 in. and they require a steady feed. As with any blade, you won’t get a clean edge if the board bows during the cut. Examples: Freud LM74R010, $60; Amana 610301, $78.

Miter Saw Blade

Your miter saw should have a miter saw blade, characterized by a low or negative hook. If most of the material you cut is 1-in.-thick or less, go with 80 teeth. Examples: DeWalt #DW3219PT, $55; Ridge Carbide RS1000, $135.

On a miter saw, the blade enters the wood from above, so teeth that angle forward (as on general-purpose and combination blades) tend to lift the workpiece. On a sliding miter or radial-arm saw, a blade with an aggressive hook angle can grab the wood and pull itself through—a real safety hazard.

It Ain’t Just the Blade

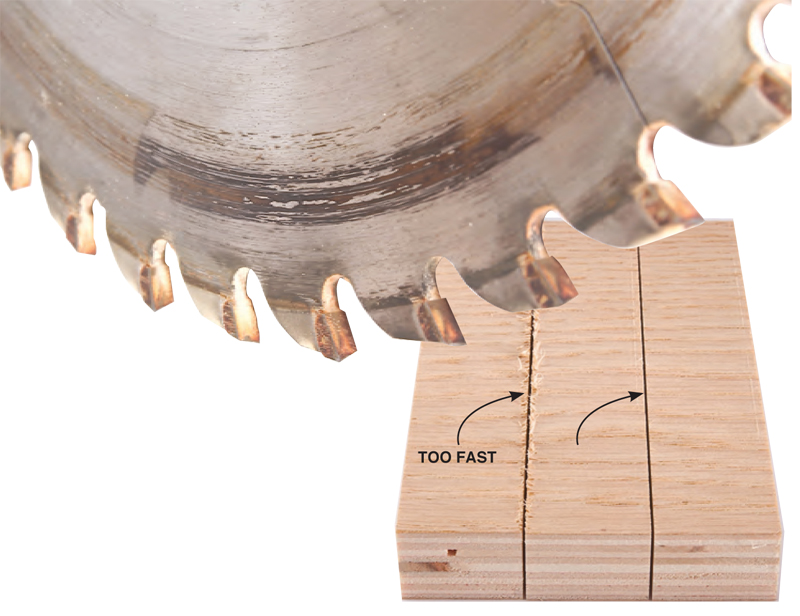

The world’s best blade will produce third-rate results if you don’t use it correctly or maintain it properly.

Routine cleaning should be a priority. Allowed to accumulate, pitch can cause overheating, because it significantly reduces the tolerance between the teeth and the wood. Overheating weakens the carbide, so the teeth become dull more quickly. Today’s biodegradable blade cleaners (such as OxiSolv Blade & Bit Cleaner) make it easy to keep your blades pitch-free.

Good technique is just as important as a good blade. A ragged cut results from a feed rate that is too fast. Feed rates that are too slow or unsteady can easily produce results that are just as unsightly.

Letting your blade go too long before resharpening is another mistake, because it shortens the blade’s life. The duller the teeth get, the more rounded over they become. That means more carbide must be removed to renew the edge.

Confessions of a One-Blade Junkie

I used to love my workhorse blade. I kept it in my saw all the time. It ripped and crosscut in hardwood and construction grade lumber. I used it to cut grooves and dadoes, tenons and lap joints. I raked across it to create coved moldings. It cut plywood, particleboard, and melamine. It has been a trusted friend that has given me years of good service.

Now that I’ve seen what specialty blades can do, though, I can’t go back. Their amazingly clean cuts make my eyes pop. Why should I settle for good results when I can get great results? I’ll always love my workhorse blade, but I can’t be a one-blade woodworker anymore.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.

Just a note for those considering a Sawstop Table saw. Coated blades defeat the safety feature of the blade. The sensor can’t read the capacitance of your body through the teflon coating.